Photography has developed into a ubiquitous form through the accessibility of camera phones, digital platforms and online connectivity. We now exist in a world of deep fakes and daily streamed content where the lens is used as a mirror, an informant, a weapon and an advocate for false truths, subjective realities and political propaganda.

Dorothea Lange (1895-1965) was a trailblazing female photographer who was committed to telling the human story through raw, honest and intimate portraits. She utilised the power of photography to raise public awareness of the effects of the Great Depression and global inequities, reminding audiences of their civic responsibilities to one another.

Towards the end of her life, Lange noted that “all photographs – not only those that are so called ‘documentary’ – can be fortified by words.” MoMA, New York, hosts the first exhibition of Lange in over 50 years, bringing together both iconic and lesser-known works that reflect upon how the written word can, and has, illuminated her compelling visual documentation. Sarah Meister, Curator, Department of Photography, shares some insights into the show.

A: The exhibition offers new insights into Lange’s practice through a range of archival and written materials. Why do you think it’s so important to revisit her works at this time, and with a connection to words?

SM: Lange’s concern for less fortunate, overlooked individuals, combined with her success in using photography (and words) to address these inequities, encourages each of us to reflect on our own civic responsibilities. Every day we encounter combinations of words and pictures – illuminating and incendiary, poetic and pragmatic, on the printed page and on Instagram – and this exhibition hopes to foster an increased attention to the ways in which each can amplify (or undermine) our response to the other mode of communication.

A: Can you discuss where these written materials have come from and how they engage with the images – both conceptually and stylistically?

SM: The exhibition’s written materials and accompanying catalogue fall into two categories: the first consists primarily of archival material that surrounded Lange’s photographs during her lifetime: magazines, books, correspondence, newspaper articles and more. The other represents a chorus of distinguished voices who graciously accepted our invitation to respond to Lange’s photographs from their contemporary perspectives. These include artists, as well as a range of writers and thinkers. We were delighted when each of them said yes.

A: Lange also wrote photo-essays in and kept notes which have informed governmental reports. How did she reflect upon the written word in relation to visual media? How did the two coalesce and connect with each other?

SM: I’m not sure it’s accurate to say that Lange wrote many photo-essays, although it is certainly true that she reflected carefully on the matter, and her photographs were published in two photo-essays in Life magazine. In a letter to John Szarkowski in June 1965 when she was refining the titles for her MoMA retrospective, she wrote: “Am working on the captions. This is not a simple clerical matter, but a process, for they should carry not only factual information, but also added clues to attitudes, relationships and meanings. They are the connective tissue, and in explaining the function of the captions, as I am doing now, I believe we are extending our medium.” And as Beaumont Newhall wrote shortly after her death, “Dorothea had a sense of words as acute as her sense of the picture. Not enough has been said of it.” In many ways this exhibition is an answer to Newhall’s call.

A: Lange was committed to social justice. She believed in the power of photography to deliver messages and defend marginalised groups. How does this exhibition celebrate that fact?

SM: Lange’s commitment to social justice – using photography to draw attention to inequality and human suffering – is foundational to any serious consideration of her work, including this one. From the very beginning of her career, when her photographs were featured alongside an article by Paul Taylor in Survey Graphic, through the posthumous appearance of images from her Public Defender series in the National Lawyers’ Guild book Minimizing Racism in Jury Selection, one might argue that every section of this exhibition celebrates this aspect of her work.

A: Many of the images included are incredibly well-known, such as Migrant Mother. What are some of the new, perhaps unseen, highlights from the show?

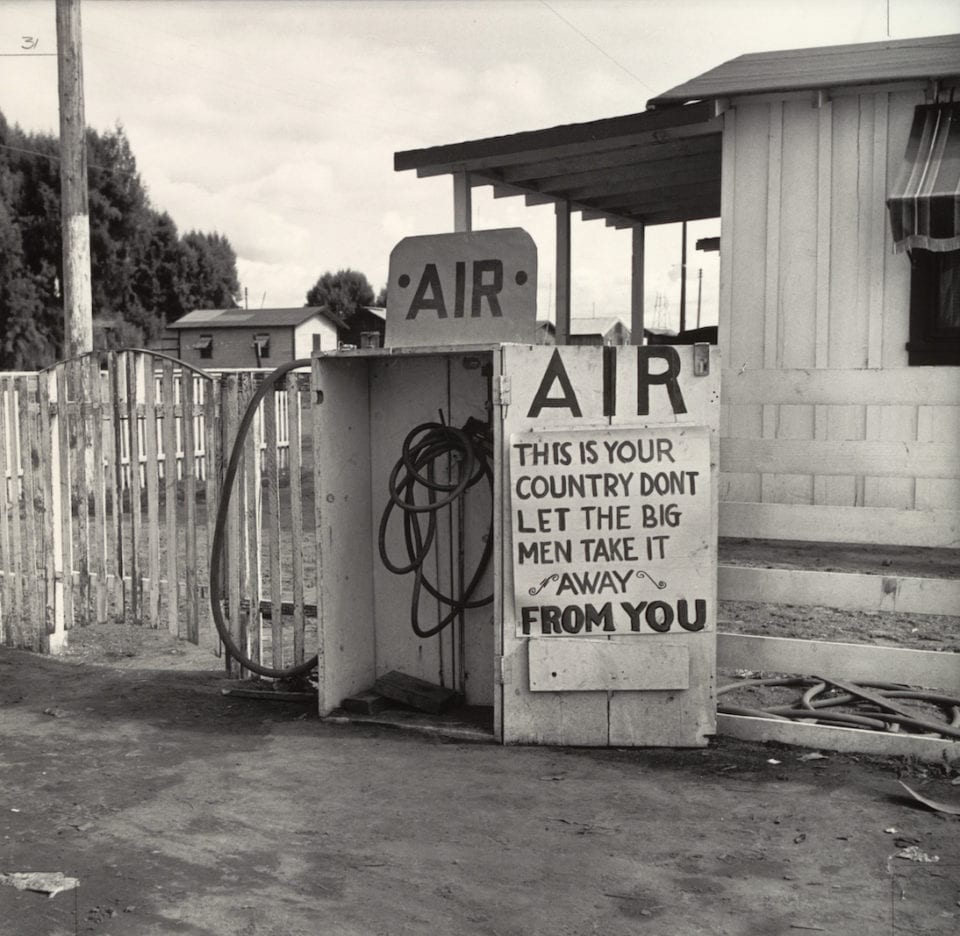

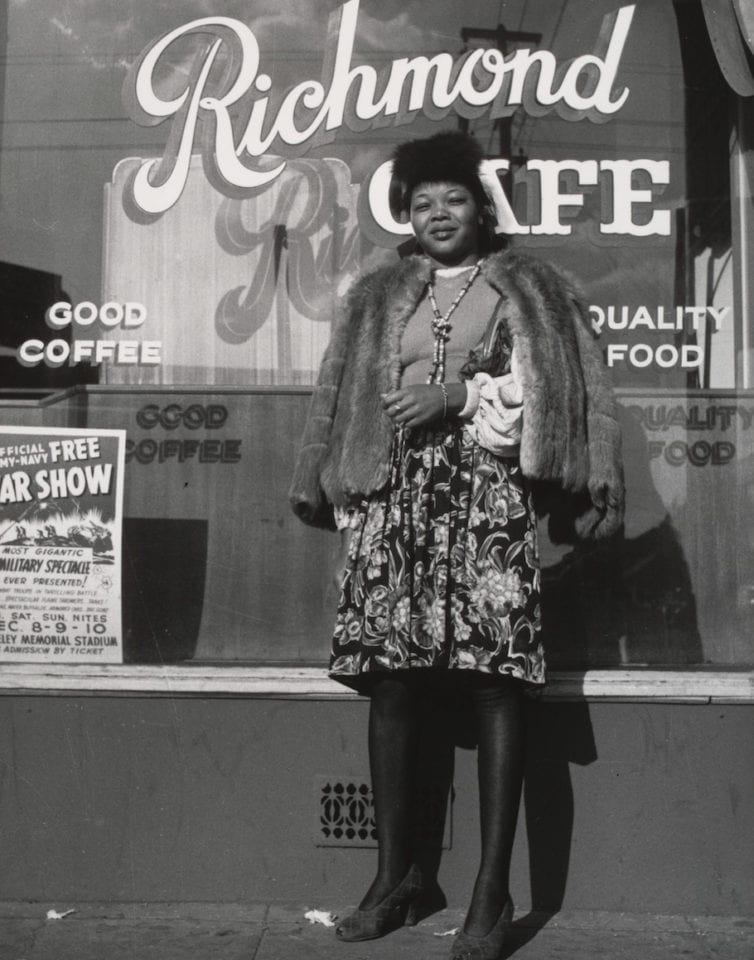

SM: We are very fortunate that the Museum Collection – from which every work in this exhibition is drawn – is expansive enough to include iconic pieces such as Migrant Mother (1936) and White Angel Bread Line (1933) as well as many others that will be less familiar to our audiences. As we were doing the research for the show, we continued to encounter pictures of words that seemed particularly urgent to include as expressions of the broader social climate in which she worked: she photographed an African-American shipyard worker in Richmond, for instance, from a low angle that both heroised her figure and juxtaposed it against the discomfiting words “serve you” looming nearby.

We are also thrilled to be working with the artist Sam Contis and the poet Tess Taylor to incorporate their independent engagements with Lange’s work. I am struck by the ways in which they each gravitate towards images by Lange that are decidedly less familiar, pointing to the fact that there is more to Lange’s achievement than we have typically understood. By including Sam’s new book, Day Sleeper, and Tess’s new book, Last West, into the exhibition space (in comfortable reading areas), we are asking our audiences to consider these fresh approaches to unfamiliar aspects of Lange’s work.

A: In the curatorial process, what new elements did you learn about Lange’s wider practice or intentions?

SM: Throughout this process I benefitted from the brilliant research assistance of my colleagues River Bullock, Jane Pierce, and Madeline Weisburg who tracked down historical combinations of words and pictures that dramatically expand our understanding of her wider practice. We are including several of these original modes of circulation in the exhibition, which should allow our audiences to enjoy a similar sense of discovery, even with some of Lange’s best-known photographs.

A: This exhibition draws from a large collection of works at MoMA. Can you describe Lange’s relationship with the institution and a brief history of her involvement?

SM:The earliest acquisitions of Lange’s work occurred even before the Department of Photography was formally established: gifts from the Farm Security Administration and a San Francisco-based collector named Albert M. Bender. Beaumont Newhall was the Museum’s first photography curator, and he included Lange’s Migrant Mother (then known as Pea Picker Family, California) in the Department’s inaugural exhibition, Sixty Photographs: A Survey of Camera Esthetics (31 December 1940 – 12 January, 1941). Lange was very close with Edward Steichen, who became Director of the Department in 1947, and he frequently presented her work at MoMA, including a one-person display within Diogenes with a Camera II, which opened in November 1952. Lange was instrumental in the planning of Steichen’s landmark 1955 exhibition, The Family of Man, which also featured nine of her photographs. Steichen’s successor, John Szarkowski, while keen to establish his independent approach to the medium, held Lange in equally high regard: his 1966 retrospective of her work is widely recognized as a definitive one, and the last time her work was exhibited at MoMA in a comprehensive fashion.

A: In a time of sheer political upheaval and a sense of mistrust and precariousness in social community, what do you hope audiences will take away from this show?

SM: I am struck by the ways in which Lange’s practice connects with people across generations, and by her prescient attention to social, economic and environmental concerns. Her images seems to foster a sense of compassion that transcends politics, and my hope is that audiences will leave the exhibition inspired by her commitment to help others. It also seems that heightened attention to the ways in which words and pictures inflect one another is as valuable today as it has ever been.

Kate Simpson

Dorothea Lange: Words & Pictures is at MoMA, New York, from 9 February. For more information, click here.

Credits:

1. Dorothea Lange. Tractored Out, Childress County, Texas. 1938. Gelatin silver print, 9 5/16 x 12 13/16″ (23.6 x 32.6 cm). The Museum of Modern Art, New York.

2. Dorothea Lange. Kern County, California. 1938. Gelatin silver print, 12 7/16 x 12 1/2″ (31.6 x 31.7 cm). The Museum of Modern Art, New York.

3. Dorothea Lange. Richmond, California. 1942. Gelatin silver print, 7 3/8 x 6 5/8″ (18.8 x 16.9 cm). The Museum of Modern Art, New York.

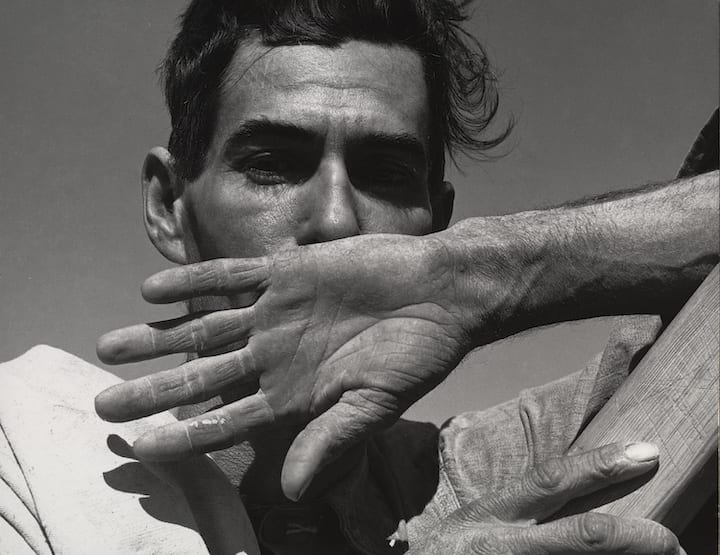

4. Dorothea Lange. Migratory Cotton Picker, Eloy, Arizona. November 1940. Gelatin silver print, 19 15/16 x 23 13/16 (50.760.5 cm). The Museum of Modern Art, New York.

5. Dorothea Lange. Man Stepping from Cable Car, San Francisco. 1956. Gelatin silver print, 9 3/4 x 6 7/16″ (24.8 x 16.4 cm). The Museum of Modern Art, New York.

6. Dorothea Lange. Richmond, California. 1942. Gelatin silver print, 9 x 7 11/16″ (24.7 x 19.5 cm). The Museum of Modern Art, New York.