In the late 1820s, Joseph Nicéphore Niépce captured the view from his upstairs window in Burgundy, France. It was the first photograph, made with a technique known as heliography, which involved coating a pewter plate in natural tar and developing it through light exposure. This single shot marked the beginning of a new era: the age of the camera. Just thirty years later, the Royal Photographic Society was founded with the objective of making the art and science of visual storytelling more widely available. The organisation has been a cornerstone of the community ever since, predating the first colour photograph, taken by James Clark Maxwell in 1861, and continuing to influence the field through the emergence of avant-garde artists during the 1920s and 1930s; the invention of Kodak and Polaroid; the rise of the camera phone; through to today, where AI and digital manipulation signal a new frontier of image-making. Today, the RPS is a world-leading hub, made up of seasoned artists and dedicated academics.

It is also responsible for the world’s longest running photography exhibition, renowned for showcasing the diversity of lens-based art. This year marks the 166th iteration, which will feature 113 prints from 51 practitioners. The International Photography Exhibition prides itself on reflecting the current moment and 2025’s submissions are no exception, with many artists focusing on today’s most pressing topics, such as environmental issues, identity, community, family and culture. They are a testament to how contemporary camerawork engages with and captures the world as it is, creating images that are both visually compelling and culturally significant. The finalists’ images are currently on display at Saatchi Gallery, London. Victoria Humphries, CEO of the Royal Photographic Society, says: “This is another edition that pushes the boundaries of creative expression and celebrates the diversity and evolution of photography. When you view this exhibition and see the same themes evolving from every corner of the world you can’t underestimate the importance of the IPE in bringing these works together.”

Lydia Goldblatt is the winner of this year’s IPE Award, the highest accolade given out to the finalists. The British artist received the prize for the series, Fugue, which explores the complex and nebulous maternal experience. The works consider love and grief, mothering and the loss of a mother, as well as intimacy and distance. It’s a deeply personal series, drawn from Goldblatt’s own experiences. After having a child, she found herself unable to take pictures. It was only after her own mother died that she returned to the camera, documenting her home and city. Yet, the series seamlessly transcends the individual, tackling universal feelings and inherently political ideas. It’s made all the more potent when you find out they were taken during the Covid-19 pandemic, when people were forced to stay indoors and familial relationships, caregiving duties and the pressure of parenthood were heightened. Goldblatt’s young daughters are a constant presence – in the small hands pressed against a wooden bench, the two legs tip toeing across the back of a chair, the small figure in fancy dress, brandishing a garden rake. They are joyful moments, but also reminders of the constant demands that come with raising children.

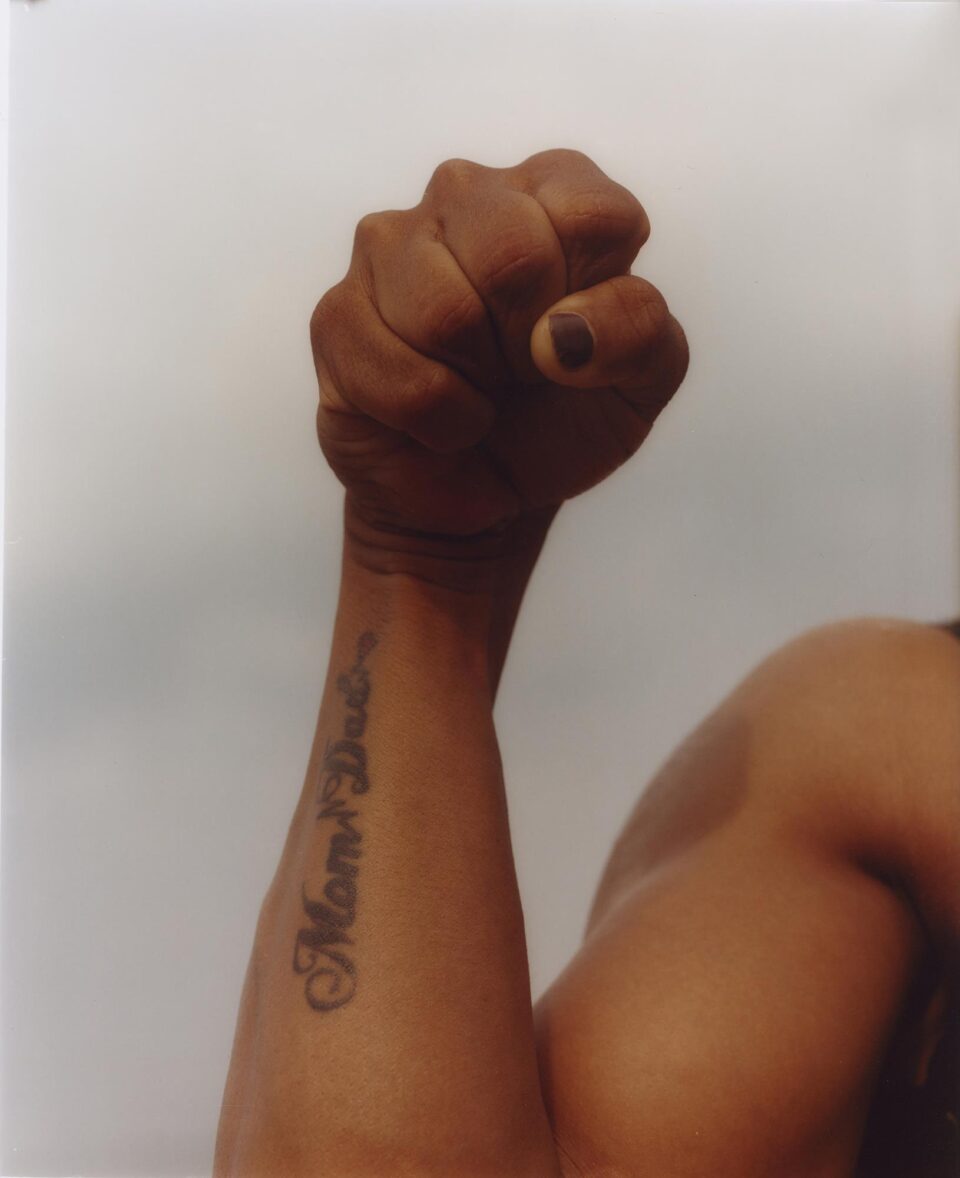

Keerthana Kunnath received the Under 30s Award for Not What You Saw. The series centres on South Indian female body builders who challenge entrenched gender and beauty norms by embracing physical strength, a trait often associated with masculinity. The portraits are set against backdrops typical of the area, like beaches, Indian homes and lush, green foliage. The setting only serves to heighten the contrast between the traditional landscape and these women, who are pushing boundaries and changing minds. Kunnath also dressed her subjects in authentic garments, which would be instantly recognisable to those from the region. The defined muscles and confident expressions may inspire nothing but admiration from many viewers, but the artist explains: “they have to regularly work around the complex physical and emotional aspect of building and maintaining their physique, while fighting the deeply ingrained expectations of how a ‘woman’ should look and what they can pursue as a ‘respectable career.’” Not What You Saw invites comparisons with another recent award-winner. The 2024 Taylor Wessing Photo Portrait Prize gave first place to Steph Wilson’s Sonam, an image which similarly sought to question ideas of acceptability by documenting unconventional and “imperfect” examples of motherhood.

Goldblatt and Kunnath are just two of more than 50 remarkable exhibiting creatives. Each one adds to the Royal Photographic Society’s commendable aim of tackling today’s urgent problems. Jocelyn Allen and Thomas Dryden-Kelsey both echo Goldblatt’s exploration of what it means to be a parent today. Allen’s Puke Portraits I & II candidly documents her nausea whilst pregnant with both of her children, whilst Oh Me, Oh Mãe I & II is her account of raising a young family. Elsewhere, Thomas Dryden-Kelsey’s ongoing project Raising Doron is the result of he and his wife choosing to adopt. The process was long, arduous and uncertain, but concluded with the welcoming of two brothers. The resulting pictures are tender, truthfully reflecting a happy home. Meanwhile, other featured artists grapple with nationhood and identity. John Boaz engages with his surrounding landscape and neighbours in This Rose I Call Home, considering what it means to be part of a local community, whilst Raeann Kit-Yee Cheung embraces her dual heritage to create works that focus on historical Chinese immigrants in China.

The Royal Photographic Society remains a pillar of contemporary art, both preserving the legacy of lens-based art and celebrating those who are redefining it. That this competition has existed for 166 iterations is testament to the enduring power of photography and its ability to adapt and evolve as the world changes. The introduction of AI, the proliferation of digitally altered images and the ubiquitous nature of social media means that photography has firmly entered a new age. If the perseverance of the RPS, and the talent of those it platforms, is anything to go by, the future of the artform is in safe hands.

RPS 166th International Photography Exhibition is at Saatchi Gallery until 18 September: saatchigallery.com

Words: Emma Jacob

Image credits:

1. Kunnath Keerthana, Aishu. Courtesy of The Royal Photographic Society.

2. Lydia Goldblatt, Folds. Courtesy of The Royal Photographic Society.

3. Ana Paganini, Our Lady of Fatima. Courtesy of The Royal Photographic Society.

4. Mat Hay, Felipe Barrera Aguirre, traditional Chinampero farmer and agroecology teacher. Courtesy of The Royal Photographic Society.

5. Lydia Goldblatt, Flame. Courtesy of The Royal Photographic Society.

6. Kunnath Keerthana, Sandra. Courtesy of The Royal Photographic Society.