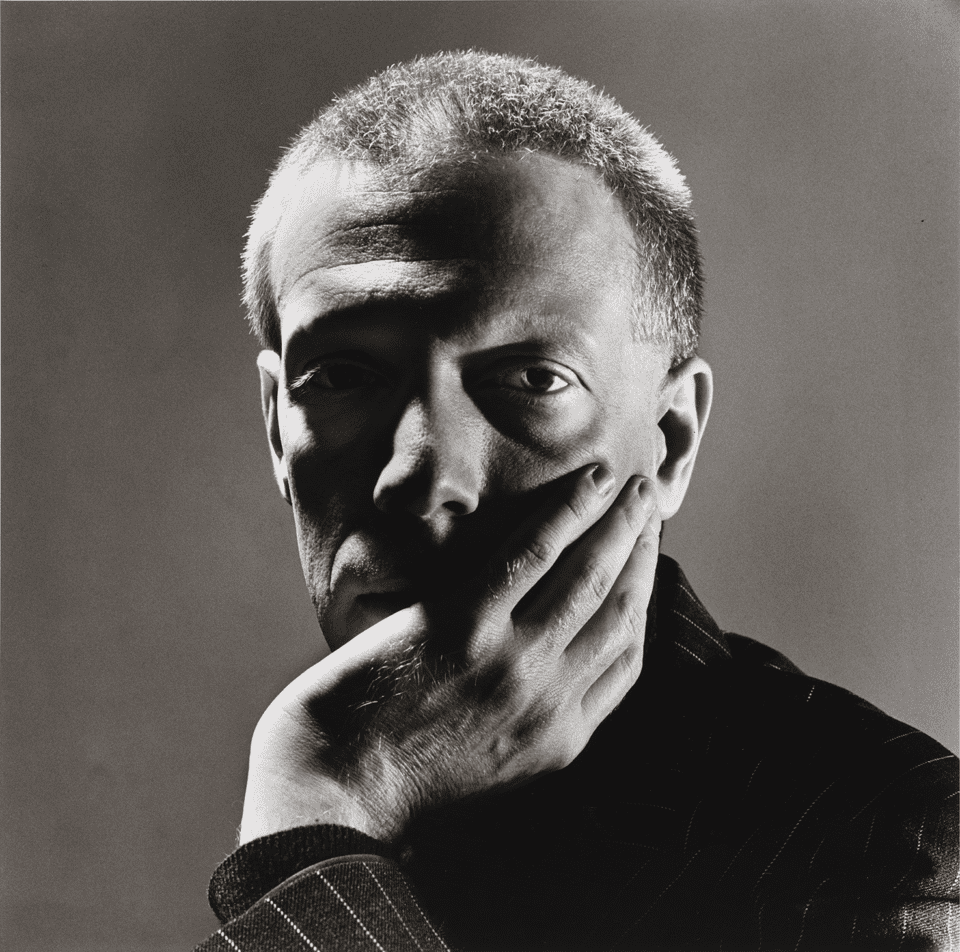

Peter Hujar was a leading figure in the New York art world of the 1970s and early 1980s. The artist’s principal concern was portraiture – of friends and denizens of the downtown scene, whom he encountered on the street, shot in his apartment studio or sought out backstage in drag and performance venues. His expansive range also gave attention to architectural, landscape and street photography. However, at his death in 1987 from AIDS-related illness, his oeuvre was largely unknown. Now, these images are gaining the recognition they deserve. Eyes Open in the Dark, presented by Raven Row in London, is the first posthumous exhibition to have access to the complete span of the artist’s works. It focuses on later pictures, when his emergence from a debilitating depression in 1976 brought about a new expansiveness. The show also reveals a darkening tone in his 1980s photography, as the AIDS crisis devastated the LGBTQIA+ community and Hujar entered into dialogue with the younger artist David Wojnarowicz. We spoke to co-curator and biographer John Douglas Millar about the process of putting the show together, why Hujar’s images are still resonant today and his hopes for the exhibition.

A: How would you describe the evolution of Peter Hujar’s style from his early work to the mature style showcased in this exhibition?

JM: There’s a line that says that Hujar’s photography arrived fully formed, and there is some truth to that in the sense that his unique “manner of looking” is there from the start. Take for instance his 1950s images of children with cerebral palsy made in Florence at an institute run by the Catholic Church; the way he allows his subjects to come to him as themselves without judgment or fetishism, the apparent suspension of the power relation between photographer and subject, these are all present already. Like a therapist he gives his subject time and an environment in which something within them can emerge and become manifest on the photographic paper. It has to do with allowing for intimacy, and sometimes love, I think. Early on though his influences remain somewhat unresolved. In what we are calling, perhaps a little uncomfortably, his “later” or “mature” style several things have shifted. The influence of the social upheavals of the late 1960s and 1970s are all over his work and affect the development of his style, even if he is in no way a tendentious or didactic artist. With the rise of gay rights after Stonewall his subject matter opens onto a new and more overt eroticism, and the show certainly reflects this. In the early 1970s, for instance, he makes his first prints of male orgasm. The economic and social world emerges in other ways too. Deindustrialisation and economic recession are present in his urban photography during this period. He shoots around Manhattan like Atget around Paris – and there is a literal and figurative darkening. In 1976, he takes a photograph from the summit of the World Trade Center that perhaps embodies some of this most directly, it scans across the East River to the former naval base and docks on the Brooklyn Waterfront and also catches the edge of the Lower East Side and the financial district. It’s a kind of physiognomic image of both the conditions that make his world possible, his version of bohemia (deindustrialisation, cheap rents, available space) and the forces that will destroy it (real estate development, the new economy, urban zoning).

A: Can you discuss the relationship between Hujar and David Wojnarowicz and how their art influenced one another during such a pivotal era?

JM: Hujar took on the role of something like a mentor to a younger generation of artists and performers during the 1970s, people like John Edward Heys, Agosto Machado, Gary Schneider, Cookie Mueller and Nan Goldin, amongst many others. This role found its most nourishing and profound expression in his relationship with David Wojanrowicz. They met in late 1980 or very early 1981 and after a brief sexual relationship, settled into a bond that is difficult to describe in conventional terms; it was not quite father and son, not quite lovers, not quite brothers. As Wojnarowicz’s partner Tom Rauffenbart put it, they were “both more than and less than lovers.” It was the primary relationship for both men up until Peter’s death. Hujar was key to Wojnarowicz recognising himself as a visual artist, and Wojnarowicz helped lift Hujar out of the depressions he suffered ever more frequently as the 1980s progressed. Wojnarowicz would drive him out of Manhattan to explore the post-industrial landscapes of New Jersey to engage his attention beyond immediate struggles. I don’t think it can be overstated how important they were to each other. It’s interesting to look at contact sheets from their scouting trips together, where each makes an image of the same subject. For instance, there is an image of a dead dog in the exhibition that Wojnarowicz also made photographs of, and seeing where their aesthetic concerns meet and depart is fascinating.

A: Hujar’s work is deeply influenced by personal loss and the AIDS crisis. How do you see these themes shaping his later photography, particularly his portraits?

JM: This is a complicated question. Because Hujar is one of AIDS’ famous victims his work is often read back from that history which, given that Hujar’s work was always saturnine and haunted by mortality, is inevitable. But Peter never made work overtly concerning the AIDS crisis, he did not shoot many of his friends ill. When he himself was diagnosed in early 1987 he ceased working in the darkroom altogether. The fact that so many of the subjects of his portraits died from the disease means that the work becomes a retrospectively charged memento mori, but it is important to keep in mind that it wasn’t necessarily conceived as such. I think the crisis appears in slightly more subtle ways. In 1986 Peter made a solo exhibition at Gracie Mansion, a show that would turn out to be the last in his lifetime, though again it is important to bear in mind he didn’t know that at the time, there’s no sense in which he considered it a final statement. As I remarked, in the 1970s his work is marked by the expansion of sexual liberation, he makes extraordinary nudes and erotically charged work. He is exploring the boundaries between eroticism, pornography and classicism, but in the 1986 show there are no male nudes. The body is hardly present at all. There are, however, a lot of images of blighted landscapes or ruined architecture, and I’d suggest that that is where the crisis is visible in his work, in the displacement of the nude and the appearance of a ruined lifeworld.

A: What were the most significant challenges in curating an exhibition with access to the full span of Hujar’s work for the first time?

JM: I don’t think challenges would be the right word, pleasures more like. My co-curator Gary Schneider and I settled quite early on the idea that we wanted to present the best of his later work, so the through line has been quite consistent. In a sense Joel Smith’s 2018 show at the Morgan Library in New York was the necessary retrospective of Peter’s work that brought him to much wider attention, and that liberated us to do something more personal and esoteric. Gary was close friends with Peter, and I think that is present in the show too. Though I wouldn’t want to speak for Gary, I will say that he has prepared a large number of the prints for the exhibition and so in a very material way there is an intimate engagement for him with Peter’s photographic intelligence and their shared history as friends. That has to resonate.

A: Hujar worked across multiple genres, including architectural, landscape, and street photography. How do these genres interplay in the exhibition to reflect his approach to photography?

It is often said that Hujar was a portraitist whatever he was photographing. That’s kind of true, but I think it has to do with the inherent animism he recognised in all things. Everything he shot vibrates with it. Hujar’s work is often in a consistent format and in his Gracie Mansion show he made sure that no image sat directly next to another of the same genre, no animal portrait next to another animal, no landscape next to another landscape and so on. While in part I think this was a practical question, he wanted as much work as possible on the wall, it was also a conceptual and formal one. What can we say about the being of a horse and the being of a human or a plant, what is the same, what is different, what kind of attention and empathy do we owe them? I think it speaks to Hujar’s spiritual and philosophical concerns. In the exhibition we have certainly sought to examine and play with these questions.

A: How do you situate Hujar’s photography within the broader cultural and artistic context of downtown New York in the 1970s and 1980s?

JM: Another great question. I think Hujar’s work sits, in some ways, quite uncomfortably there. Hujar is often situated within the over mythologised downtown scene of the period, but I think that is a more anthropological than aesthetic connection. Hujar is a late modernist. His work is often a manipulation of absences, and it can, I think, be quite reasonably characterised as essentially existentialist. It is concerned with the frailty and integrity of identity. It doesn’t share concerns, or at least not in any straightforward way, with the post-Pictures generation work of the era, and certainly not with conceptual photography more generally. It doesn’t seem very connected to the neoexpressionist bells and whistles of the late 1970s and early 1980s. Hujar simply couldn’t find his place in that world, aesthetically or financially, he didn’t know how to negotiate it, nor did he want to. He recognised the anachronism in his work, remarking often that what he was doing was essentially the same as the Victorians. Interestingly, it may be that very anachronism that makes his work resonate in the present.

A: What do you hope viewers will take away from this exhibition?

Beyond these art historical and theoretical concerns, ultimately I hope viewers get a sense of just how wonderful an artist Hujar was. Despite his burgeoning reputation, I still think he is underknown. To me at least, all these questions are important, but we have also made a selection that we think represents some of the very finest, if not always the most obvious, examples of his photography.

Peter Hujar: Eyes Open in the Dark is at Raven Row, London from 30 January: ravenrow.org

Words: Emma Jacob and John Millar

Image Credits:

1 & 6. Peter Hujar, Untitled, 1984.

2. Peter Hujar, Ethyl Eichelberger (II), 1981.

3. Peter Hujar, Stephen Varble (III), Soho, New York, 1976.

4. Peter Hujar, Ethyl Eichelberger, 1979.

5. Peter Hujar, Paul Thek, Florida, 1957.