“The shapes of time are the prey we want to capture. The time of history is too coarse and brief to be an evenly granular duration as the physicists suppose for nature time; it is more like a sea occupied by innumerable forms or a finite number of types.” – George Kubler, The Shape of Time, 1962.

We interview Susan May, Global Artistic Director, White Cube, for their latest online show.

A: When did you begin planning this exhibition?

SM:Work on the exhibition began just a few weeks into lockdown and somehow, we managed to turn it around faster than any other exhibition I have done before.

A: In light of the pandemic, routines have been changed and thus, society’s concept of time has been altered, both in the domestic and commercial world. How does this show explore such ideas?

SM: Being placed into a form of suspended animation has meant that, for many of us, time becomes a more elastic concept. Without the usual markers, our perception and memory of time spent becomes more fluid, with days seemingly rolling from one into another. For me, at least, it feels like it has both accelerated and crawled by. In thinking about this, I was reminded of how many artists, writers and philosophers have attempted to unpack the mystery of time, from Aristotle and St Augustine onwards. And so, it seemed like a hugely rich subject to explore, both as something that is measured through chronometry and as a phenomenon that is experienced as a temporal continuum.

A: How did you choose the artists to be included?

SM: Taking the dichotomy of time as something both objective and subjective as a starting point, I looked for artworks that focused on measurable markers and the perception of time. For example, literally marking time through inscription, numbers or indexical markers in the work of On Kawara, Hanne Darboven and Darren Almond. Thinking about how time is perceived brought to mind the work of Olafur Eliasson, who first introduced me to the writing of Henri Bergson. Time and Free Willwritten by Bergson in 1889, posited the concept of duration, which Olafur’s The small morning cloudencapsulates beautifully. And I also wanted to reference some of the broader themes around time and space, including works by Cerith Wyn Evans and Josiah McElheny. It is such a broad topic I could have doubled the number of artists but both time and space were also against me!

A: Time is used as both a concept and subject matter, with many of the works incorporating counters and spatial measurements. Are there any pieces that play with incohesion or a kind of inconsistency between the idea and its form?

SM: Darren Almond’s Perfect Time (3×2) plays with the slippage between the imposed “structure” of time and our comprehension of it. Using a series of digital flip clocks, familiar in train stations and synchronised to the ‘correct’ time, Almond re-arranged the number sections. The result is a series of partial digits rendered abstract, simultaneously incomprehensible yet curiously familiar. In a way it asks us “what is real time?”

A: Though time is – in our reality – constant, linear and expansive. How do the artists explore the possibility of variables, abstractions and alternate timelines? How do they explore larger metaphysical constructs, interrogating our very experience of duration?

SM: The theoretical physicist Carlos Rovelli has asked “do we exist in time or does time exist in us?” which simply put takes us to the heart of the challenge when attempting to explain the concept of time. For me, Mona Hatoum’s YOU ARE STILL HEREneatly condenses these questions and other metaphysical concerns by placing the viewer at its centre. Whilst we generally think of time as a linear construct, I also wanted to look at how circularity plays a part in our understanding, such as in the work of Tatsuo Miyajima. Using LED counters, his sculptures and installations count from one to nine in mesmeric repetition, reflecting the circle of life.

A: With a broad concept such as time, many artists and visitors may be drawn to consider larger, arcane parts of life, illuminating aspects of mortality, rituals of birth and death. What place does the everyday have within the show? Are there any works that circle around ideas of mundanity and the quotidian?

SM: Christian Marclay, who famously made one of the most significant artworks about time with The Clock, also created a series of animations that succinctly incorporate the idea of time and the everyday. He took hundreds of still images of detritus he spotted on the streets during his daily walks to and from his studio in London. Noticing recurring – and at times random – objects, such as discarded cotton buds, he organised the images into categories that when shown in quick succession give the sense of a moving image.

A: Has the exhibition made you personally re-assess how you spend time or how you value it?

SM: Working on the exhibition in such a condensed period has made me acutely aware of how fluid our sense of time has been during the past few months. And as we start to cautiously venture into our new reality, I’m reminded what a precious commodity it is.

About Time is on view until 16 July. To find out more, click here.

Credits:

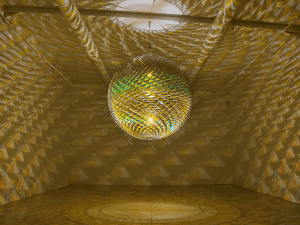

1. Josiah McElheny, Frozen Structure, 2008.

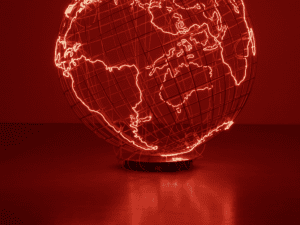

2. Darren Almond, Light of Time X, 2018.

3. Tatsuo Miyajima, Bi- Counter No. 2, 1988.

4. Haim Steinbach, going going gone, 1999.

5. Josiah McElheny, Frozen Structure, 2008

6. Josiah McElheny Crystal Landscape Painting (Sentinels), 2017.