“I was interested in the history of prostitution in Chile. I wanted to know more about women, I wanted to know more about myself, I wanted to know lots of things.” These are the words of Chilean photographer Paz Errázuriz (b. 1944) whose work focuses on alienation, representation and womanhood. The artist began her practice in the 1980s, focusing on marginalised communities such as sex workers, psychiatric patients, and circus performers during the military dictatorship of Chile. Today, Errázuriz is known for her discerning and critical eye, as well as a compassionate and dedicated practice that sought a strong and caring relationships with her subjects. Unfinished Stories at Maison de l’Amérique Latine brings together 120 prints from 15 of the artist’s series. These include the emblematic Adam’s Apple (1982-7) as well as three never seen before series, Próceres (1983), SepurZarco (2016) and Ñuble (2019).

Errázuriz’s collections are rooted in the brutal context of General Pinochet’s dictatorship. They uncover the history of a country ruled by a repressive regime. Between 1973 to 1990, Chile, under a military dictatorship, saw the murder of over 3,000 people and the torture of 29,000. It witnessed a government that installed neo-liberal style economic measures, implementing controversial policies such as the abolishment of minimum wages, the privatisation of pensions and the cutback of corporation taxes. By 1982, the country’s economy crashed. According to the British Online Archives, more than 45% of the population were living in poverty whilst 30% were facing unemployment.

Errázuriz was born in Santiago, Chile and worked as a teacher prior to embarking upon her self-taught artistic career in the 1970s. She explains, “My early years as a professional photographer correspond with those of the dictatorship. Photography enabled me to express myself in my own way and to participate in the resistance. It’s strange to observe the extent to which hostile, dangerous eras can stimulate artists. All this creative energy being expressed by metaphors. That was the case in Chile in the 1980s.” The artist took her first photographs in the 1970s. Her striking black and white portraits pointed to the invisibility of certain groups and challenged the conventions of visual representation. From north to south Chile, even as far as Patagonia, she provided a powerful overview of those whom society considered to be different, through individual and collective stories. In response to the violent repression of Chilean photojournalists, in 1981, the artist cofounded the Association of Independent Photographers (AFI), a group of photographers who supported one another as creators and activists, sharing venues and legal resources.

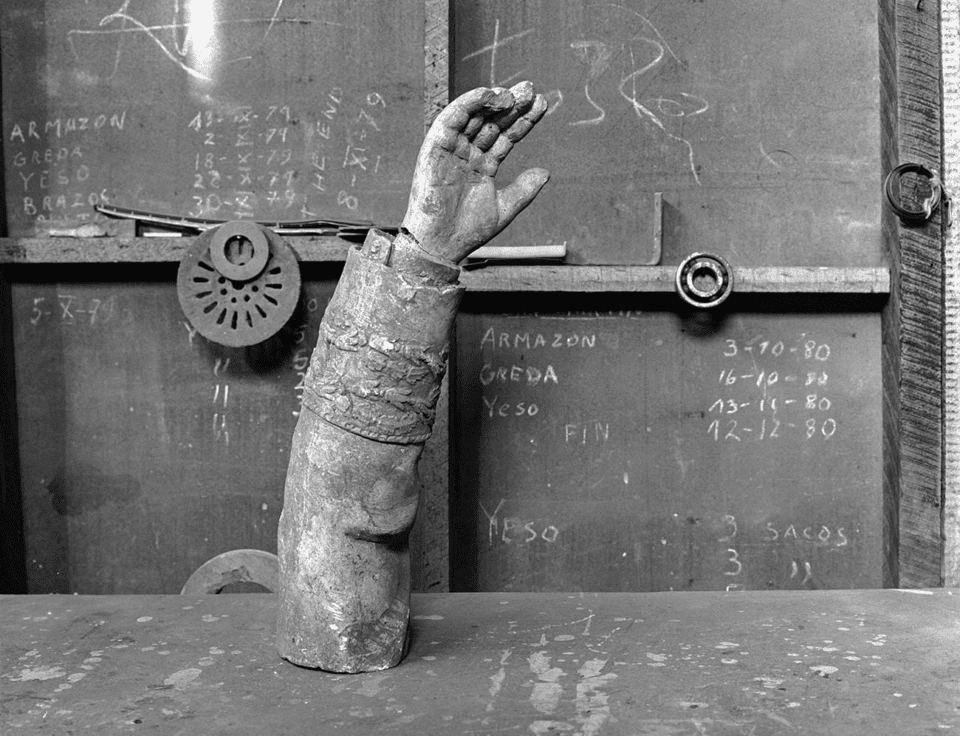

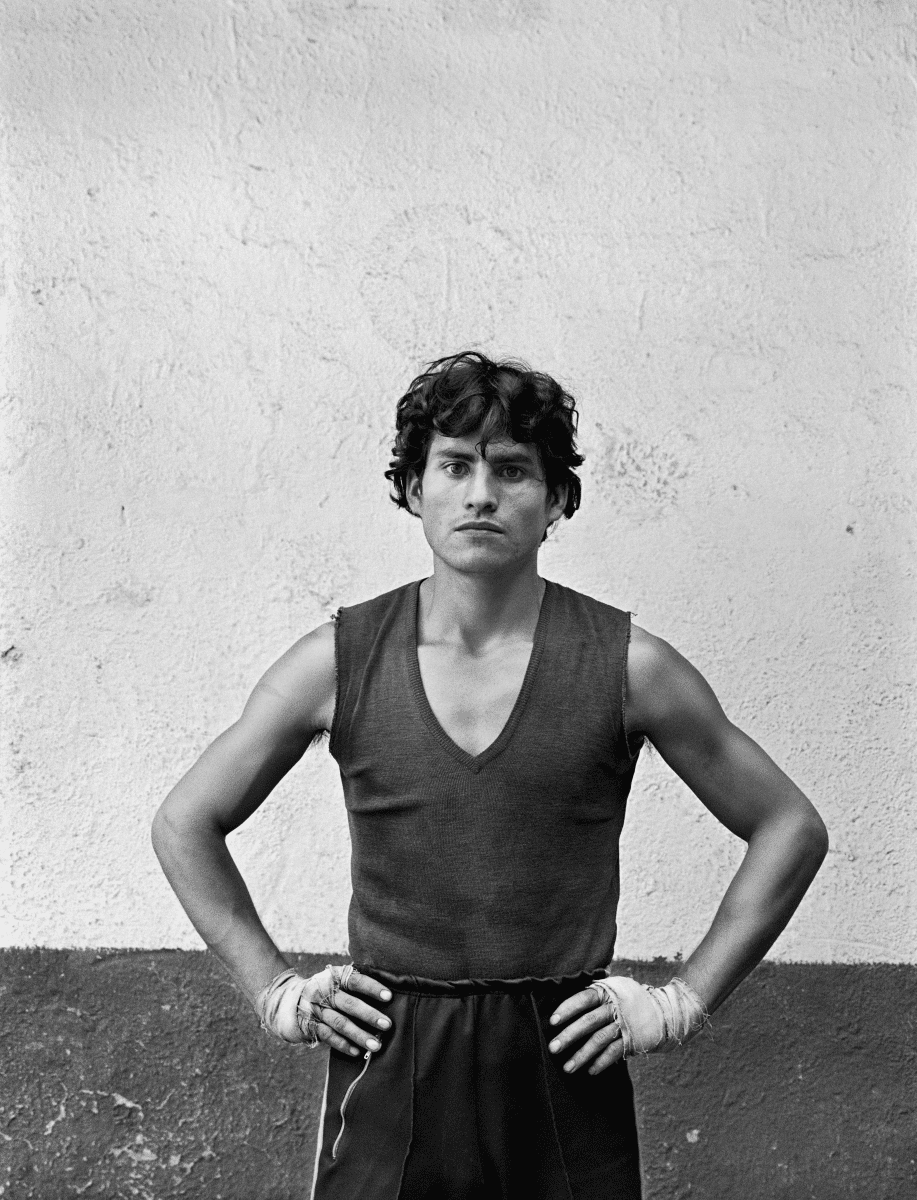

Iconic images such as Boxer VII (1987) also display. The picture is part of a larger series of the same name, depicting portraits of young men, isolated against a wall. They reveal a masculinity defined by sport, but also rooted in social spaces. Far from flaunting their bodies, the athletes appear vulnerable, bent over, or with their hands on their hips. Elsewhere, La Manzana de Adán (Adam’s Apple) (1982-7) exhibits. Intimate portraits show the daily lives of cross-dresser and transgender sex workers. After numerous visits to La Palmera and La Carlina, brothels in Santiago, Errázuriz embedded herself in the community, documenting the neighbourhood from within. Against a dictatorship that condemned gender non-conformity and homosexuality, the artist created a platform for marginalised and alternative communities to be seen. La Manzana de Adán in particular, focuses on two siblings, Evelyn and Pilar and their mother Mercedes. In a black and white photograph, they hold each other, their eyes, momentarily, meeting the camera’s gaze. In another portrait titled Evelyn, La Palmera, Santiago (1989), a figure in a sleeveless silk top and dark lipstick poses against a strip of brown wallpaper. These pictures are emblematic of liberation. They refuse silence. Instead, they indicate powerful and enduring ways of life outside a heteronormative regime.

Unfinished Stories is marked by the advocacy and respect it champions for those who have previously been ignored, stifled and punished. Errázuriz demonstrates the social and political activism of photography. In these stark, revealing compositions, it acts as a mode of resistance and revolution. As Maison de l’Amérique Latine curator Béatrice Andrieux writes, “Throughout her entire career, a social conscience in the face of the injustices in her country was to serve as the driving force behind Errázuriz’s work. She succeeded in finding her own form of resistance, having seen so many of those close to her either imprisoned, assassinated, or flee the country to escape the violence of Pinochet’s regime.” This is an exhibition that still holds relevance today. It asks what it means to have agency, to be able to tell our story against all odds.

Paz Errázuriz, Unfinished Stories | Until 20 December

Words: Chloe Elliott

Image Credits:

Evelyn, La Palmera ,Santiago. “Adam’s apple” series, 1982-1987. Gelatin silver print from 1989, 26×39.3cm. Private Collection,Paris.

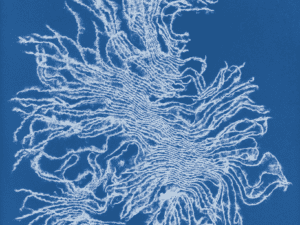

Untitled. “Próceres” (Dignitaries) series, 1983. Digital print from 2023, 36 x 46 cm. Studio Paz Errázuriz, Santiago, courtesy Mor Charpentier.

Boxer VII. “Boxer” series. Silver print, 1987, 40 x 30cm. Courtesy Mor Charpentier.

La Carlina, Vivaceta, Santiago. “Adam’s apple” series, 1987. Gelatin silver print on baryta-coated paper from 1989, 36,2 x 24,1 cm. Private Collection,Paris.

TangoVIII. “Tango” series, 1988. Silver print, 50x60cm. Courtesy Mor Charpentier.