Artificial Intelligence and the rise of digital post-production techniques have changed the nature of images forever. How much longer until the unsettling sheen of an AI-generated or heavily manipulated visual will be ironed out beyond recognition? Is this something to fear, mourn, celebrate – or all of the above? Rapid digital and technological advancements may have destabilised the already unstable idea of “truth” in photography, but at the same time, new creative frontiers have opened up for artists. A wider array of digital tools means more manipulation techniques to experiment with.

It’s now possible to explore heightened surreal and abstract realms without the time, labour and expenses of sophisticated physical sets. There’s also the case for a sort of AI assistant: a technology that can analyse a photographer’s images, mark out the style, “listen” to the artist’s stated intentions, and suggest tools, edits, textures, filters and more. Is it cheating? Or is it a kind of cyborgian human-machine collaboration, leading to the formal expansion of digital abstraction?

A surge in surrealism, futurism and conceptual photography is underway. It is a contemporary trend driven not only by technological progress but also because algorithms reward them, as they perform well on online platforms. Changes in environmental, social and existential discourses are another factor. Climate anxiety, ecocriticism and the Anthropocene, global political instability including ongoing genocides, and an increasing distrust and despair in state authorities worldwide push the needle on what kind of images we collectively crave, both to consume and to make. When inundated with incessant visual documentation of social and environmental destruction – the absolute worst of humanity’s capacities – a fantastical, ethereal or off-kilter image that says: “what if all this could be different?” Or simply: “take a break from this reality” seems a welcome, essential, balm.

Swiss-born contemporary artist and photographer Daniela Droz (b. 1982) makes work about light, abstraction and perception. She pushes the traditional boundaries of the medium, and reminds us that these kinds of photographs have been present, and integral, throughout the medium’s history. “There have been a lot of historic photographers, like Florence Henri or László Moholy-Nagy, for example, who have worked with abstract and experimental images, but perhaps they’ve been given less visibility than other artists.” Moholy-Nagy was a revolutionary painter and photographer from Hungary, known to be “relentlessly experimental”, as stated by The New Yorker’s then-chief art critic Peter Schjeldahl. Between the 1920s – 1930s, the artist coined the term Neues Sehen, meaning New Vision, which suggested that the camera could create an entirely new field of vision beyond the capabilities of the human eye. More than a term, New Vision was a framework of operation and artistic approach for Moholy-Nagy’s practice. It is a foundation upon which artistic, scientific and technological innovation has been built. He pioneered the creative use of equipment like telescopes, microscopes and radiography and is famous for experimenting with the photogram, a cameraless photographic image made by directly placing objects on top of light-sensitive materials.

Avant-garde artist Man Ray was another cameraless practitioner. He worked in a similar way, creating renowned Rayograph prints. Florence Henri, meanwhile, who was likely further overlooked in art history on the grounds of gender, was Moholy-Nagy’s student. She became known for her “manipulation of mirrors, prisms and reflective objects to frame, isolate, double and otherwise interact with her subjects – one of the most distinctive and adventurous features of her photographic work,” writes Anna Linehan for the International Center of Photography. Henri, Ray and Moholy-Nagy stood on the shoulders of earlier pioneers, such as Anna Atkins, active in the 1840s, who made botanical cyanotype prints.

Technological progress picked up immense momentum in the following decades, with the invention of point-and-shoot photography and the digital camera, as well as the rise of the internet, social media, tools such as Photoshop and now AI generators. The line between fiction and reality is as porous as ever, and heavy scepticism naturally arises. In the 1990s, critic Hal Foster published The Return of the Real, a book in which he argues “the avant-garde returns to us from the future, repositioned by innovative practice in the present.”

Foster asserted that art and theory were pivoting away from avant-garde approaches, back to being “grounded in the materiality of actual bodies and social sites.” We can see this parallel – of yearning for more authenticity and nostalgia – as more of the future hurtles into our present. There’s been an increased resurgence of film photography, Polaroids and older, more analogue processes. According to Digital Camera World, Leica reported a tenfold increase in film camera sales from 2015 to 2023, prompting the company to announce “the return of analogue”, attributed to a resurgence amongst Gen Z and millennials. This “return to the real” has rippled across other media as well, such as the revival of vinyl, valued for its perceived warmth and connection to the past. Indeed, this print magazine has weathered the digital storm. It’s evident that, as the desire for pixel-perfection ensues, a counterculture oriented towards honesty, rawness and relatability runs parallel. People crave visual imperfections and constraints, seeing them as more genuine.

Droz echoes a similar attitude shift in contemporary photographers’ practices, including her own. “Perhaps we’re now in an era where digital technology and artificial intelligence are taking on so much importance that some people, like me, feel more and more the need to go back to the basics, to matter, to the sensitive surface and light,” she shares. “And who knows, maybe it’s thanks to this digital era that we’re giving more visibility to artists who are looking for this love of matter and not pixels.” For her, whilst digital retouching and AI can manufacture elements of the past, such as adding grain, “nothing can replace the chemical reactions and surprises that we have by experimenting with real materials.”

Her career as a photographer began following a degree from École Cantonale d’Art de Lausanne, with various commissions for magazines and other commercial clients, specialising in still lives. “As I was making the images,” she recalls, “I began to notice that what I liked doing most was building the backdrops for the objects to be photographed.” Her sets were already geometric and minimalist. One day she asked herself: “Why not remove the objects and just photograph the set?” This was the start of her artistic trajectory in earnest.

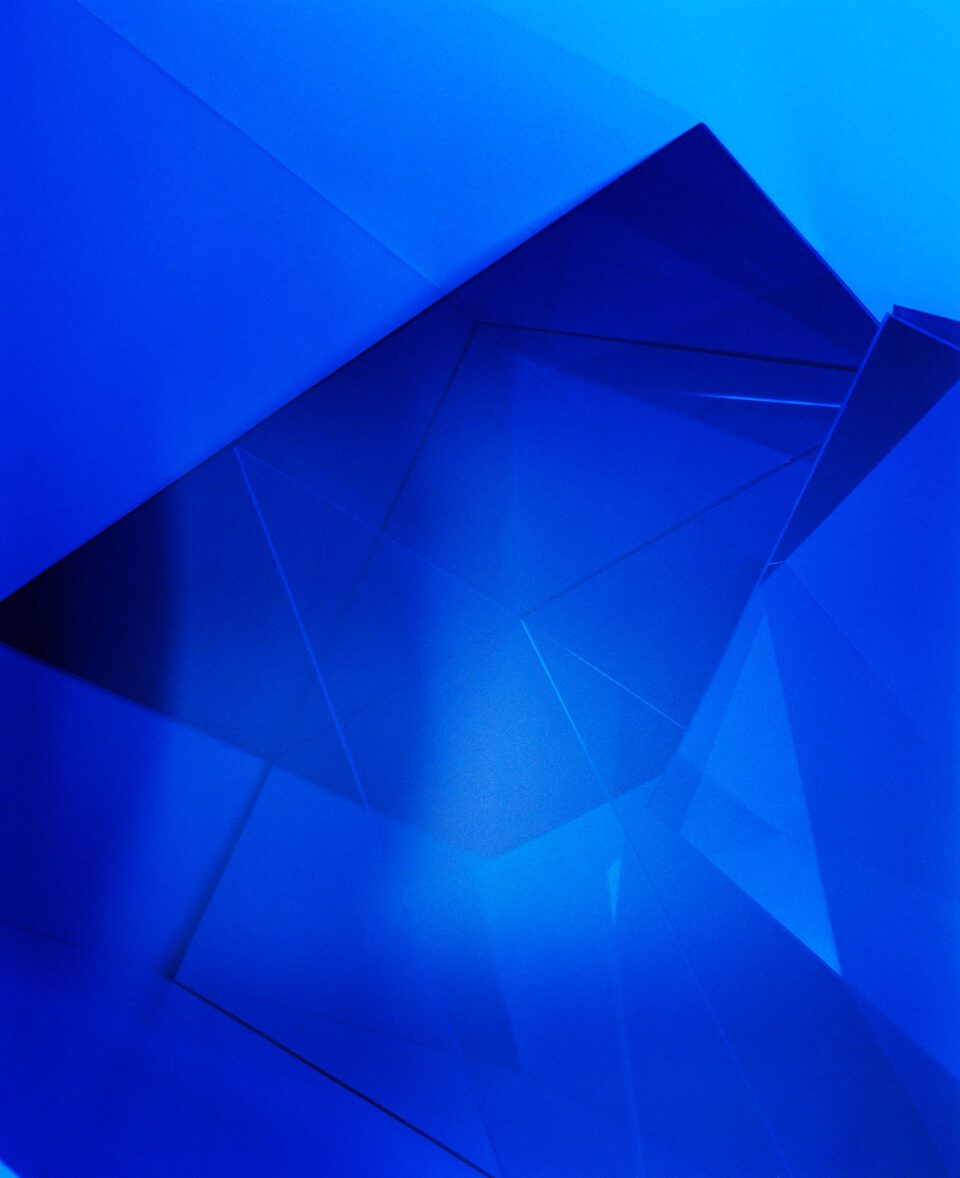

Largely influenced by everyday life and observing the sky, light and how it permeates our living spaces, Droz experiments with cameraless techniques, light manipulation and the integration of materials like glass and mirrors into her work, lending them a sculptural dimension. “If I had to name one person who has really marked me with their way of working, I’d say [Italian fashion photographer] Paolo Roversi. I find his work to be a reflection of his soul, as well as of the models. I also like to observe and read work from other fields such as architecture and sculpture, for example Brâncuși, Isamu Noguchi, Peter Zumthor, Tadao Ando.” Such influences are evident in her use of materials like plexiglass, paper, mirrors and sheets of glass, creating “architectural and geometric sculptures that [she] freeze[s] in time using light.” They are a “testimony of ephemeral installations” built in-studio.

The Interferenz exhibition is a prime example, featuring 24 geometric compositions which play with shadows to prompt dialogue about how light shapes the experience of space. The show is part of Swiss Photomonth, taking place in collaboration with Fotostiftung Schweiz, Winterthur, at Balgrist University Hospital. “My primary desire is always to take visitors on a journey, to let them interpret my images and experience them like windows onto new landscapes. This yearning is even greater given the location, in the hope that it might give a breath of fresh air to the thoughts of the people in hospital.” Droz’s visuals are fascinating portals away from the present, to be traversed by visitors, workers and patients.

Droz is far from alone in her play with the photographic medium. Turner Prize-winner, German photographer and another fellow chronicler of everyday life in surprising new ways, Wolfgang Tillmans (b. 1968), has impacted both the installation of photography and its production techniques. He has influenced how printed media is curated and displayed in galleries by combining larger-scale prints with smaller and even unframed works that are not hung, rather pinned or taped to the wall.

Tillmans blurs the constructed boundary between displaying capital A “art”, and the presentation and accumulation of visual culture within a space. Tillmans, too, often uses cameraless development methods and creates abstract images through chemical processes or light exposure, challenging viewers to think about photography beyond a tool for representing reality. The results are images that feel just as much manipulated as an AI visual. They take us back in time, but, beyond imitating film images, they instead mimic a more acoustic method of the ages: painting. “It is important that these are not paintings [however],” he has said about his abstract work. “As the eye recognises these as photographic, the association machine in the head connects them to reality, whereas a painting is always understood by the eye as mark making by the artist.”

The art world has been increasingly paying attention to the changes taking place in this field. There have been large institutional shows, such as Abstracted Light: Experimental Photography, currently open at the Getty Center in Los Angeles, and there’s an annual Experimental Photo Festival in Barcelona. In 2018, Tate hosted the mammoth Shape of Light, 100 Years of Photography and Abstract Art exhibition. Getty Center’s show, in particular, takes a scientific look at the history of the medium. It deals with the materiality of photography: demystifying how it uses a kind of magical alchemy to transform light and chemicals into prints, even sculptures and installations. Could this signal, perhaps, a shift in the critical angle of how photography is analysed? As long as the world continues to complicate the borders between reality and illusion, and as technology sprints forward, there will be many more things to say on this fascinating intersection.

Daniela Droz – Interferenz | Fotostiftung Schweiz, Winterthur

Until 31 August 2025

Words: Vamika Sinha

Image credits:

1. Daniela Droz, Lux, (2016). Image courtesy of the artist.

2. Daniela Droz, Heure Bleue, Heure Doree, (2021). Image courtesy of the artist.

3. Daniela Droz, Lux, (2016). Image courtesy of the artist.

4. Daniela Droz, Heure Bleue, Heure Doree, (2021). Image courtesy of the artist.

5. Daniela Droz, Résonances, (2019) Image courtesy of the artist.