Arctic sea ice helps keep the planet cool. It moderates the global climate, with snow-covered polar regions reflecting up to 90 percent of incoming solar radiation. But, when these areas melt, the oceans are left to absorb the sun’s energy. Sea temperatures rise as a result – making the poles the most sensitive regions to climate change on Earth. The thickness and extent of summer sea ice in the Arctic has shown a dramatic decline since the 1980s. Moreover, data from July 2024 tells us that it is diminishing at an above average pace. During the first two weeks of the month, 121,000 square kilometres per day was lost. Figure show 2023 to be the warmest year since global records began in 1850, by a wide margin.

It’s been 10 years since Olafur Eliasson and Minik Rosing’s first Ice Watch, for which the artists installed 12 large blocks of ice – cast off from Greenland and harvested at a fjord outside Nuuk – in a clock formation at Copenhagen’s City Hall Square. Since then, it has been recreated in multiple locations: Paris, for the UN Climate Conference, and in London, in front of the Tate Modern. Its goal is to raise awareness by forcing people to watch it melt in a real time. Other creatives working in this space include Julian Charrière, whose film Towards No Earthly Pole (2019) “gives the dark side of the polar region a new voice.” He also spent eight hours melting an iceberg with a gas blowtorch. In photography, Florian Ledoux is a self-confessed “polar obsessive” who captures striking imagery for BBC, Disney, Netflix and National Geographic. Then there’s Evgenia Arbugaeva, whose magical realist compositions focus on the lives of people in the Russian Arctic – her homeland. She’s dedicated to documenting remote places and telling the stories of the people who inhabit them.

These names mark a new generation of artists who are bridging anthropology, art and environmental science. Laure Winants (b. 1991) has earned a place amongst them. The artist-researcher, who lives between Paris and Brussels, has recently been recognised by .tiff 2024, a talent initiative from FOMU, Antwerp, which celebrates emerging photographers living or working in Belgium. For the 12th edition, Winants joins a shortlist of 10 creatives, including Angyvir Padilla, Catherine Lemblé, Elise Dervichian & Lina Wielant, Ksenia Kuleshova, Marcel Top, Marens van Leunen, Nathan Mbouebe, Romane Iskaria and Romain Cavallin. The idea: to offer a fresh perspective on the possibilities of photography, and to connect audiences with what is happening amongst emerging creators right now. It reflects society through “a healthy critical lens.” We caught up with Winants after she returned from a recent expedition.

A: How would you describe the work you do? What is the key driving force or idea behind your projects?

LW: I am a researcher and field-based visual artist who practices situated science. It’s important to me to be in a location, to experience the area and to consider all the elements – like the sun, light and ice. By working on site, I’m able to establish a dialogue between all the different factors, from the chemical composition of the air to the spectrum of sunlight. I work with a pluridisciplinary group of researchers: bioacousticians, oceanographers and glaciologists. The idea is that by working together, we are taking a more-than-human perspective. We don’t just look at entities from our point of view. Instead, we hold the microphone at the same level as the element being studied. I want to give a voice directly to the entities; in this way, they are included in the dialogue.

A: Can you talk us through your process? What does an average day on an expedition look like?

LW: My fieldwork is a laboratory for testing ways of seeing, thinking, acting and knowing. Before I board a research vessel or travel into the Arctic, I prepare and do a lot of reading. But as soon as I embark on the expedition, I leave everything at the door. I have many conversations and dialogues with everyone on the team: the chef, the person in charge, sailors and scientists. These viewpoints nourish the project. I don’t get onto these boats with a pre-conceptualised idea of what I’m going to do. The path I take really depends on what they are doing, so there’s a lot of influence from the scientists on the ship. For example, when I set up my artist’s studio in the heart of the Arctic ice pack in 2022, I didn’t know that the four-month polar expedition would focus so much on light and the colour spectrum.

A: You’re talking about Time Capsule, a series which came out of that trip. How did you end on this voyage?

LW: I worked with the Polar Institute on this one. It was after a residency that I joined one of their proper research boats. The project was about ice, light and optical refraction, but also understanding climate. The experiments were numerous: capturing the composition of light, the acoustic inflections of icebergs, printing the chemical make-up of water, and so on. Several boreholes were drilled to take samples of permafrost, glaciers and sea ice, providing insights that take us beyond our own humanity.

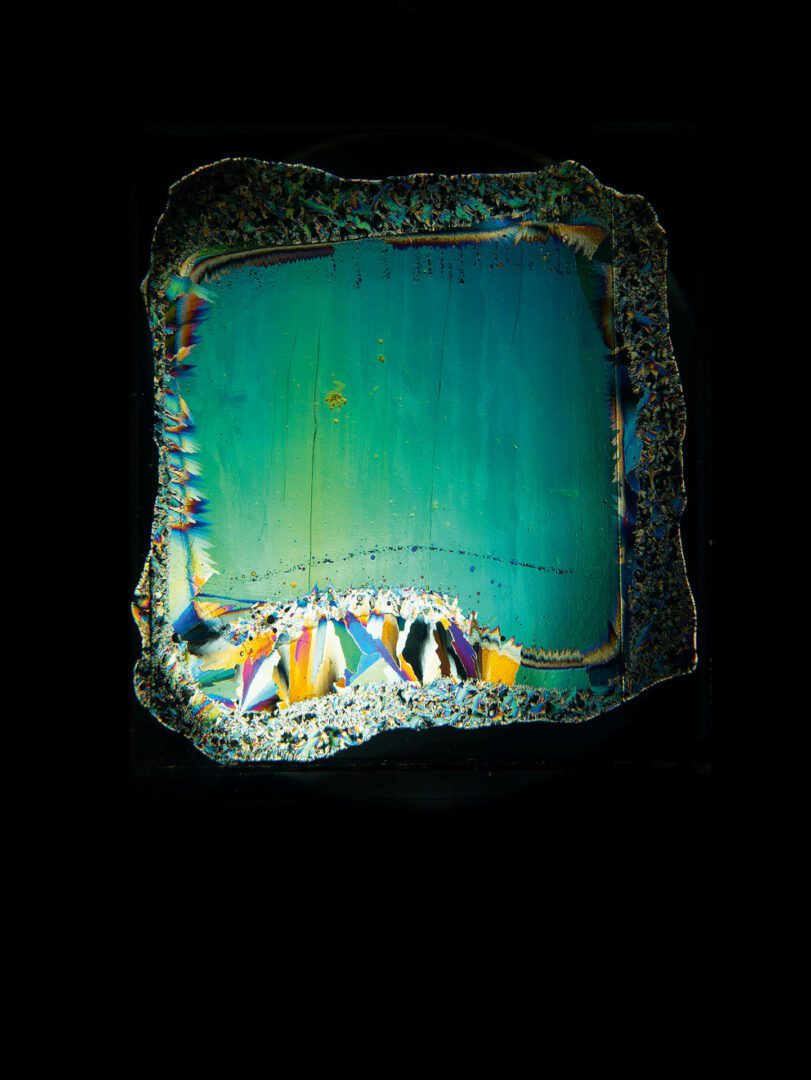

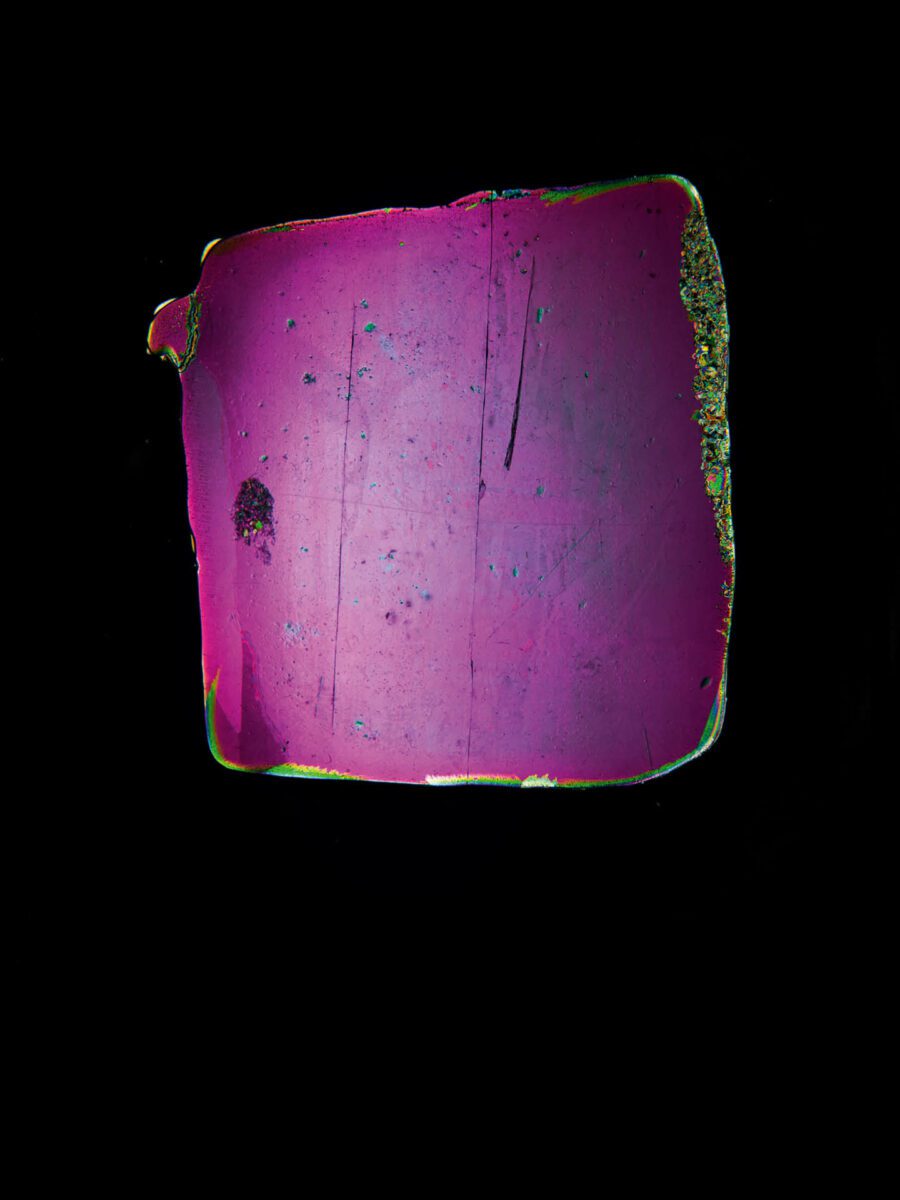

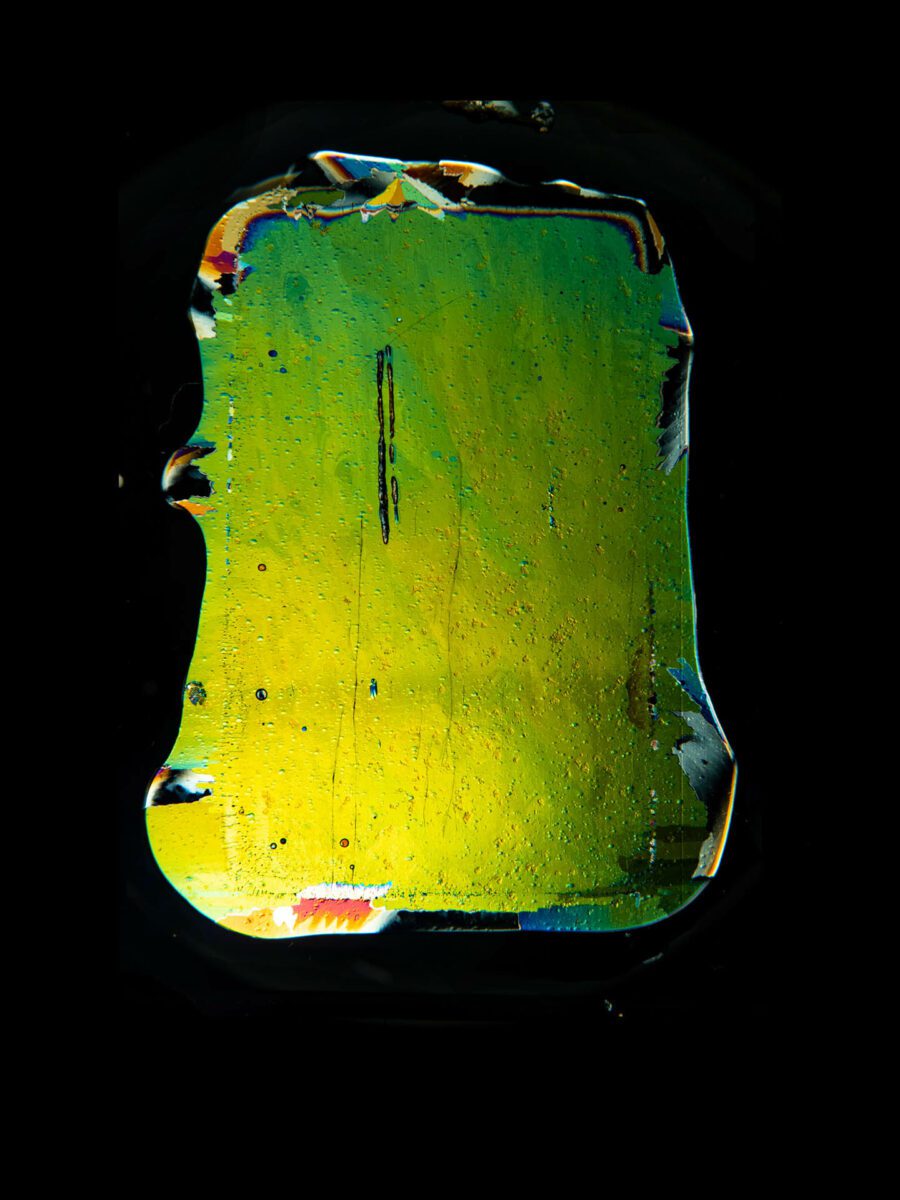

A: For Time Capsule, you used analogue photography techniques to create bright, abstract pictures from ice. The results are striking: stark black backdrops juxtaposed against magenta, blue and turquoise shapes. Can you explain how these striking images were made?

LW: This is an experimental series exploring the phenomena of light and colour in the Arctic. The works are prints of photograms onto which ice cut-outs captured on site have been affixed. Polarised light on the material reveals the composition of the cut-out. It shows the structure of the crystals but leaves a shadow over certain elements that have been present for thousands of years. I studied bubbles inside of the ice core, cutting thin sections then using them as an optical tool. Light travels through the ice and gives us a part of the spectrum, like a prism. The result is different depending on the composition of the bubbles. I wanted to visualise these patterns, so I worked with an instrument that’s called a spectrophotometer. It gave us those colours. My processes are usually cameraless. Another approach I took was to do an extraction of the sea ice and the permafrost, this time letting it melt on the top of the film, which caused a chemical reaction.

A: What exactly are we looking at here, and what does it teach us about the ice pack and its timeline?

LW: The data from these time capsules sheds light on thousands of years of history. We did a lot of drilling, and, when we drill, we go back into the past. The ice core is a record of the atmosphere spanning millennia: the perfect samples of what was happening long ago. It traverses all the way through deep geologic time up until today, whilst giving projections of the future.

A: You’ve explored some of the most extreme environments on planet Earth – from ice to fire. Can you tell us about Phenomena (2022), your work with volcanoes?

LW: The research concerned the evolution of glaciers and the rise in water levels following different scenarios. At that moment, Fagradalsfjall – a volcano in Iceland – was showing surprising levels of activity, producing carbon dioxide, hydrogen sulphide and halide gases. I followed the eruption at Meradalir with the volcanologists, from the first movements until the last tremor breath. We sampled lava in the field and took measurements using lidar, a remote sensing method that uses a pulsed laser to measure distance. We went daily to study the evolution of the eruption activity with all kinds of techniques, using the collected data to build a 3D model of the eruption.

A: Let’s go back to the very beginning. Where did everything start for you – with fine art, or science?

LW: I come from a background where more-than-human entities were very important. In terms of what came first, I grew up with ornithologists and naturalists, so we were always in the countryside or forests. Birds, and the outdoors in general, were big parts of my childhood. I was also very interested in philosophy, natural science and visual art. It’s for these reasons that I became so passionate about finding alternative, non-human routes to knowledge.

A: What’s it like working between research and the creative industries? Do you see them as completely separate disciplines, or as one and the same? How do you balance visual aesthetics with scientific rigour?

LW: Research and visual art are very much interconnected. They are both led by process but are also rooted in experimentation. It’s not a binary relationship where art is “all over the place” and scientific research is very rigorous. I don’t think there’s a gap between the two; I have strict protocols, but I also play. I think there’s common ground, and that the two disciplines meet at some point. Maybe the goals are not always the same, but there’s a lot of intuition required regardless. What’s great is that my work is equally displayed on the wall or included within research studies. Colourful depictions of the birefringence of ice, and the lidar mapping of glaciers, are complex technical images but they are also beautiful. My multidisciplinary approach allows me to make data tangible and emotionally perceptible, highlighting the interdependence of ecosystems.

A: Do you have any plans for future projects or expeditions? What are you working on at the moment?

LW: I’m doing similar colour-based investigations with another research vessel. This time, the body of work is about the deep sea and how different microorganisms function as effective markers of climate change. They capture carbon dioxide and transform it into oxygen; they are the CO2 pumps of the ocean. I’m doing a lot of undersea experimentation using pH sensitive paper – it changes colour depending on the composition of the water and the sea level at which it is placed, and it reflects the state of our oceans.

TIFF 2024 | FOMU, Antwerp | Until 18 August

Words: Frances Johnson

All images: Laure Winants, from Time Capsule, (2023). Image courtesy of the artist.