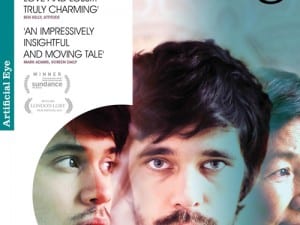

Richard Ayoade’s adaptation of the existentialist Russian novella, The Double, is a dark comedic vision that sees Jesse Eisenberg perform two opposing manifestations of the same self.

Best known for his comedy roles in the IT Crowd and The Mighty Boosh, and his award-winning directing debut, Submarine (2010), performer, writer and filmmaker Richard Ayoade’s most recent work, The Double,takes a somewhat darker turn. Adapted from an 1866 novella of the same name, written by Russian existentialist Fyodor Dostoevsky, this black comedy and love story tells the tale of a man whose life is altered irreversibly by the intrusion of his mirror image: an aesthetically identical, opposite persona.

Simon James (Jesse Eisenberg) is a meek introvert; he lives alone, labours unnoticed at his deadening office job, and he spends his evenings watching his beautiful colleague and neighbour (Mia Wasikowska) through a telescope from his apartment window. Described by a colleague as “pretty unnoticeable … a bit of a non-person,” Simon is plagued by the threat of disappearing completely: even his own mother has trouble remembering who he is when he visits her care home, the security guard at his office refuses, day after day, to recognise him, and the suicide rate of his hometown is increasingly cataclysmic (investigating officers note Simon down as “a maybe”). Often self-analysing, Simon contemplates: “I’m permanently outside myself, you could put your hand straight through me.”

Simon’s banal life takes a bizarre turn when a new arrival joins his workplace, James Simon (Eisenberg in a double role), who is, as his name suggests, Simon’s mirror image: superficially identical, but with polar opposite character traits. James is a carefree risk-taker and the centre of attention at work and play; an overconfident philanderer, he is also, most significantly, the centre of his female colleagues’ affections. James moves in across the street from Simon, within the sightlines of his telescope. Initially James’ appearance seems to offer a glint of hope for Simon: he offers him romantic advice, and Simon reciprocates by supporting James at work; however, Simon’s kindly actions are soon taken advantage of. As James begins to invade Simon’s professional and personal life with increasingly dire consequences, Simon is forced to fight back, yet in doing so, he soon realises that he is connected to James in more ways than just their shared appearance, bringing a twisted conclusion to Ayoade’s movie.

Ayoade initially discovered the script for the film via its producers, Robin C. Fox and Amina Dasmal of Alcove Entertainment, who admit that they had been “stalking” the writer and actor – who at the time was yet to make his directing debut. Having worked with Harmony Korine in 2009, it was a chance meeting with her brother, scriptwriter Avi Korine, who had been working on a re-write of The Double since 2007, which finally provided the bait that Fox and Dasmal needed. Ayoade explains his attraction to The Double: “It’s quite a strange book, and it’s got a strange ending. It seemed like a good part for an actor.” He continues: “What I liked about it was that the central idea in it was very funny to me – that someone could be your exact replica and no one would notice, and that you’d be so unremarkable that even if you pointed out the obvious to them they still wouldn’t care.”

He describes the central joke as “being like a Monty Python sketch”, comparing it to “one of those stories you hear about a famous person not being able to get into a club and they say ‘don’t you know who I am?’ But the reality is that unless you do, then they are just someone trying to get into a club. It’s that question: what are you? What you are is slightly in the eyes of other people, and what you think you are doesn’t necessarily correspond to what everyone else thinks of you. That’s why it was interesting to make it into a love story: how do you fall in love with someone if you don’t know what they’re like – and if the only thing you know about them is what you’ve observed, then the question is do you even know them at all?” The casting of Australian rising star Mia Wasikowska as Simon’s beloved Hannah is ingenious; Ayoade affirms: “she has a sort of enigmatic quality,” and appears simultaneously shy, troubled and yet quietly aware of her beauty – a conviction brought out by James during the second half of the film. “If anyone can cast Mia in something then they will; she’s timeless in a way.” Discussing both leads, Ayoade says that they “have an intelligence that’s hard to act – certain things and personal qualities, that are unactable.”

Ayoade continued to work on drafts with Avi, Eisenberg and Wasikowska were identified during this process, and were the only actors they auditioned for the roles. “It’s difficult to think of better actors than them,” Ayoade comments. The choice of Eisenberg, who has recently shot to fame due to award-winning roles in Zombieland, The Social Network and Now You See Me may seem like a commercial move (or at least a certain help rather than hindrance); however, Ayoade dismisses any notion of tactical casting: “I don’t know what makes people go and see something, but you’d hope that audiences know that Jesse’s never bad, so there’s at least stock of trust there. I think you make a movie for one person that you love rather than what a bunch of people might love. Perhaps it is counter-intuitive, but if you try to think for an audience then you’ll make something that no-one will like at all.”

Instead, it seems that Ayoade chose Eisenberg simply because “he is extraordinary, and there aren’t many actors who could play both parts and have that precision. He’s technically brilliant but also spontaneous and instinctive; he goes for the reality of things.” It’s true that Eisenberg’s performance is natural and believable, perhaps because he is an actor who really “lives” his part: “If my day ended playing Simon, I would go home miserable,” Eisenberg muses. “It was a relief to play James, because Simon was so self-hating and miserable. I definitely took on their traits. I was full of ideas when I was playing James, but playing Simon, I was so shut down; and I would want to do the scene over and over again.”

Playing two roles, in the same clothes and often superimposed so that both Simon and James appear onscreen at once, Eisenberg portrays two completely opposing characters using only differing facial expressions, tone of voice, gait and posture. Ayoade comments: “Even in a still frame, a close-up still frame, you could tell which one (Simon or James) was which. It was remarkable. Just by thinking differently he changes his appearance.” Ayoade enthuses: “It was essential that the two characters looked exactly the same as, according to the story, there’s no real reason why one person should prefer James to Simon – not because one is dressed differently to the other, or does his hair in a certain way – but they’ll both come into a room at once, and everyone will turn round and look at James rather than Simon. The movie needed to have the logic of a bad dream.” This dreamlike quality is not only achieved through the film’s central narrative, but wholeheartedly through its production design, which avoids any geographic or temporal location. Instead Ayoade achieves an other-worldliness that is necessary “as the doppelganger story is slightly mythological; you don’t want the story to be ‘once upon a time in Folkestone.’ You want it to be more generalised.”

The filming took place over a 53-day shoot, not in Folkestone, but surprisingly in a Crowthorne aircraft hangar – something that Ayoade describes as “intense because the idea was to make it all quite industrial, with hard lighting.” Additionally, the filming took place entirely at night. Ayoade continues: “It was thought that the environment wouldn’t be comfort-led – none of the chairs are cozy and none of the instruments are ergonomic – it was all built for durability rather than being consumer-driven, in any way.”

The sets are minimal and comprise overtly false-looking props, which carry the same warped humour as the narrative, reflecting what Ayoade details as “how they would have (wrongly) imagined the future in the 1950s, with everything overdesigned and massive computers doing everything.” There is also a nod to Brutalist architecture and, with Simon’s /James’ office cubicles, even the old Holborn post office sorting room, Ayoade recalls: “They would have these tiny cubicles and big chutes, and the letters would all shoot right down to someone just sitting there sorting them.” Not only do these sets reinforce the idea of a hierarchical structure, but the mix of eras is necessary to portray the idea that someone could “be totally invested in their job, in a clerk sort of way,” something he sees as “almost impossible in the modern world.” This slight jarring of reality is something that Ayoade believes “has slightly gone out of the window now – films seem to be either complete fantasy or to have a phoney advert realism, which is slightly better than your life, but pretends its real as everyone says ‘er’ a lot.”

Neither Ayoade nor Eisenberg are blockbuster disciples (tellingly, Eisenberg was compelled to work with Ayoade after watching Submarine twice over), because sometimes: “You don’t feel that involved as there’s less of a point of view and more of a distance.” Therefore Ayoade highlights Edward Hopper’s paintings, the work of David Lynch and the subjective style of Hitchcock as key influences: admiring “the idea of showing someone, demonstrating what they look at; and what they think afterwards. Doing something through a character’s eyes is something I like about films.”

Ayoade’s focus upon the individual is incredibly noticeable within The Double, and the way that he handles the brief appearances of Chris O’Dowd, Craig Roberts, Sally Hawkins, James Fox and Paddy Considine is (as is typical) far different from the conventional and recognisable “cameo” appearance. Ayoade muses: “You’re always trying to make the best case for each character – regardless of their position within the story.” The cameos are never just “showing face,” but are fully-fledged personalities with clear function, and often appear in scenes that are suggestive of theatrical tableau.

With Yasmin Paige, Noah Taylor and Wallace Shawn also playing substantial roles, Ayoade’s background seems to have provided him with a strong foundation of talented people to work with: “I’m aware it’s unusual, but I’ve always worked with them and it seems odd not to have them in, if I can, because they’re great actors. Ultimately a film is entirely about the actors; they’re the people that you follow and it’s their faces and emotions that are magnified, so really, they’re the final conduit between the audience and the film. I think it was Aki Kaurismaki (the Finnish director) who said that ‘all you really are as a film director is a football manager standing on the side-lines.” You can will something to happen, but you aren’t actually playing; you can sway the actors, but ultimately it’s them doing it.”

Ayoade’s cast are equally praising of him; Wasikowska said: “I haven’t had an experience that has been this fulfilling in all areas. He has a really sensitive way of dealing with actors and getting the best out of us.” And Eisenberg notes that working on The Double was “the most interesting experience I’ve ever had. Every scene was located in this ambiguous place and time. He never wanted anything to be standard. Often, an actor comes with his own strange ideas, and the director shapes them into a normal movie scene. Richard takes actors’ strange inclinations … and pushes them further.”

Although there is a thematic divide between the warmly lit, youthful “coming-of-age” story, Submarine, and the claustrophobic, cramped world of The Double, Ayoade’s dry wit and subjective dramatic approach clearly connects the two, creating what Eisenberg describes as “an aesthetic that is totally his own.” On the subject of personal style, Ayoade is as modest as ever: “I think style is the residue rather than the aim: it’s what comes naturally; it’s the thing of yourself that you can’t get rid of.”

Chloe Hodge