Nederlands Fotomuseum – the Dutch National Museum of Photography – has more than 6.5 million objects in its archives. That makes it one of the most significant collections in the world. Founded in 2003, the gallery is a mainstay of Dutch history, tracing how the camera has equally documented and influenced the course of the nation’s identity. This almost unparalleled influence is only set to grow, with the collection estimated to reach 7.5 million by 2028. It is only natural, then, that the museum would eventually outgrow its surroundings. This month, Nederlands Fotomuseum opens a new site at the renovated Santos warehouse in Rotterdam, offering innovative ways for visitors to experience the art and technique of photography, how it is made and why it matters. The monumental nine-story building includes exhibitions spaces, a bookshop and library open to everyone, educational studios, community spaces and a darkroom. It truly is a state-of-the-art site. The premises opens with two exhibitions: Rotterdam in Focus, which puts a spotlight on the city from 1843 to today, and Awakening in Blue, celebrating the timeless beauty of cyanotype. We caught up with Martijn van den Broek, Head of Collections, and Grace Wong-Si-Kwie, Head of Presentation and Public Outreach, to chat about the future of the museum ahead of the grand opening.

A: The move to the Santos warehouse marks a new chapter for the Nederlands Fotomuseum. How did this major undertaking first come about?

MvdB: The move to the Santos warehouse came from both necessity and ambition. For many years, the museum’s expertise, collection and international reputation had outgrown its former home. Our team and collection are truly world class, but the previous location limited our ability to make a strong impact in the city and to fully realise our ambition of becoming a state-of-the-art centre for photography. When the opportunity arose to acquire the historic Santos warehouse, everything came together. The building is not only architecturally impressive but also deeply embedded in the history of Rotterdam. It offered the scale, quality and location needed to properly house a collection of more than 6.5 million photographic objects and to make the full breadth of our work – collecting, conservation, research, exhibitions and education – visible to the public. This transition was made possible by the generous support of the Droom en Daad Foundation, which shared our conviction that this national collection deserved a permanent, purpose-built home. The move to the Santos warehouse therefore represents much more than a change of address: it enables us to rethink what a photography museum can be in the 21st century; open up our collection and expertise to a wider audience; and strengthen the international position of Dutch photography.

A: The new building makes storage and restoration visible to the public. How does this openness change the way you want visitors to understand photography?

MvdB: Photography has become more widely used than ever. That means that the image is often only seen as the story it tells. This is quite logical in the digital world. Photography is perceived as immediate and effortless, but behind every physical object in our collection usually lies something fragile, as well as a great deal of specialist knowledge, care and time. By opening up our depots and conservation studios through glass walls and curated displays, we invite visitors to see photography as material heritage that needs to be actively preserved. This openness also helps visitors to understand photography as a process rather than a finished product. They can observe how each shot is conserved, restored, described, digitised and studied, and how decisions are made about storage, display and interpretation. In doing so, we reveal the human labour and expertise that underpin the collection and ensure its survival for future generations. Ultimately, this transparency fosters a deeper appreciation of photography’s vulnerability and value.

A: The Santos warehouse is tied to global trade and colonial routes. Did this history influence how you thought about the collection or the exhibitions shown here?

MvdB: Absolutely. The Santos warehouse itself is a powerful historical symbol — it was originally built to store coffee imported from Brazil, linking Rotterdam to global trade networks and, indirectly, to the colonial histories that shaped those economies. Being housed in such a building naturally prompts us to reflect on the broader contexts in which photography was produced, collected and circulated. This awareness influenced how we approach the collection and curate exhibitions. For example, we highlight works that document colonial histories, such as photographs from the former Dutch colonies by Kassian Céphas and Augusta Curiel, situating them within a wider narrative of global connections, trade and power dynamics. It also encourages us to be critical and transparent about the provenance of objects, and to create exhibitions that don’t just present aesthetic images but invite discussion about their contexts.

A: What have been the major challenges or opportunities of curating the first show in this new space?

GWSK: The first exhibitions in the Santos warehouse have been both a tremendous opportunity and a challenge. On the opportunity side, the building’s state-of-the-art facilities — climate-controlled galleries, advanced lighting and open depots — allow us to display extremely delicate and historically significant works that were previously hidden. For the first time, visitors can see fragile negatives, vintage prints and conservation processes up close, creating a much richer, more immersive experience of the collection. At the same time, this visibility brings challenges. We had to carefully balance the narrative of the exhibitions with the technical requirements of preservation, ensuring that works are protected while still being accessible. Coordinating the opening exhibitions — Awakening in Blue and Rotterdam in Focus — meant integrating historical, aesthetic and contemporary perspectives in a way that resonates across multiple floors and formats, from cyanotypes to city photography spanning 180 years. Another challenge has been the scale: the sheer size of the new museum allows us to show more, but it also requires a curatorial strategy that guides visitors through the space thoughtfully, preventing them from feeling overwhelmed. Overall, the first exhibitions in the Santos warehouse will set a precedent for how the museum can merge scholarship, conservation and public engagement in a single, cohesive experience.

A: The Gallery of Honour of Dutch Photography shows the development of photography in the Netherlands from 1839 to today. How did you decide what from the vast archive should be included?

MvdB: It was a deeply considered process because the collection spans over 180 years and contains millions of objects. In addition to pieces from the collection, loans and works by photographers can also be seen here. We worked with a team of photography experts to identify images that are not only artistically outstanding but also socially and culturally significant. The goal was to tell the story of Dutch photography in a way that highlights both its historical evolution and its ongoing impact. We focused on several criteria: the innovation or mastery of technique; the influence of the photographer; the way the image reflects Dutch society or culture at a particular moment; and the capacity to resonate with contemporary audiences. This is why the gallery includes iconic works by Anton Corbijn, Ed van der Elsken, Rineke Dijkstra and others, alongside images that may be less known but capture pivotal moments or perspectives. Ultimately, the Gallery of Honour is curated to show the richness, diversity, and depth of Dutch photography, giving visitors both historical context and a sense of discovery.

A: Why was it important to give visitors a direct role in shaping the show through the 100th photograph?

GWSK: This was significant for several reasons. First, it emphasises that photography is not just a historical record but a living, evolving medium that continues to resonate with people today. By inviting the public to participate, we break down the traditional barrier between curator and audience, making visitors active contributors rather than passive observers. Second, it creates a sense of ownership and engagement — audiences can see their voice reflected in the exhibition, which encourages deeper connection and curiosity about the images and the stories behind them. Finally, it highlights the democratic and participatory nature of photography itself: what is considered meaningful or iconic is not fixed, but shaped by dialogue and shared experience. In this way, the 100th photograph becomes a bridge between the museum’s curatorial authority and the public’s perspective.

A: Awakening in Blue: An Ode to Cyanotype celebrates the enduring appeal of the artistic technique. How do you balance honouring its history and exploring its contemporary applications?

GWSK: Cyanotype is a medium with a rich and tangible history, and we wanted the exhibition to acknowledge that legacy while also highlighting how contemporary artists are reinterpreting it. By presenting a few early blueprints alongside modern works, visitors can see the technique’s original purpose and craftsmanship. At the same time, the new generation of artists uses cyanotype to engage with current themes — ecology, colonial histories and the body as an archive — often combining it with installation, textiles and multimedia. This creates a dialogue between past and present, showing that while the process is centuries old, it remains relevant as a tool for experimentation, storytelling and reflection. The design by MAISON the FAUX further reinforces this balance, turning the slow, tactile nature of cyanotype into an immersive, contemporary spatial experience.

A: Rotterdam has been photographed extensively for nearly two centuries. What new ways of seeing the city does Rotterdam in Focus propose?

GWSK: Rotterdam in Focus encourages visitors to see the city in unexpected ways. Rather than following a strict chronological order, the exhibition is organised around associative themes, presenting surprising viewpoints, unusual perspectives, and the layering of historical and contemporary landscapes. This is particularly interesting in Rotterdam, where the old city center has completely disappeared since the bombing in May 1940 by the Nazi’s. From early 19th century cityscapes to drone and panoramic photography today, visitors can experience the city through both intimate and expansive visions. The exhibition also highlights lesser-known archival gems, rare stereoscopic images and new commissions, showing how photography interprets the urban fabric. Ultimately, it invites audiences to question how the city evolves, who it belongs to and how collective memory is shaped through the lens of photographers.

Nederlands Fotomuseum opens at Santos Warehouse, Rotterdam on 7 February: nederlandsfotomuseum.nl

Words: Emma Jacob, Martijn van den Broek & Grace Wong-Si-Kwie

Image Credits:

1. Nederlands Fotomuseum © Photo Studio Hans Wilschut.

2. The Island of the Colorblind, 2018 © Sanne de Wilde (1987).

3. Nederlands Fotomuseum – semi-transparent ‘crown’ façade © Photo Studio Hans Wilschut.

4. Nederlands Fotomuseum – atrium and central stairwell © Photo Studio Hans Wilschut.

5. Nederlands Fotomuseum – restored warehouse interior © Photo Studio Hans Wilschut.

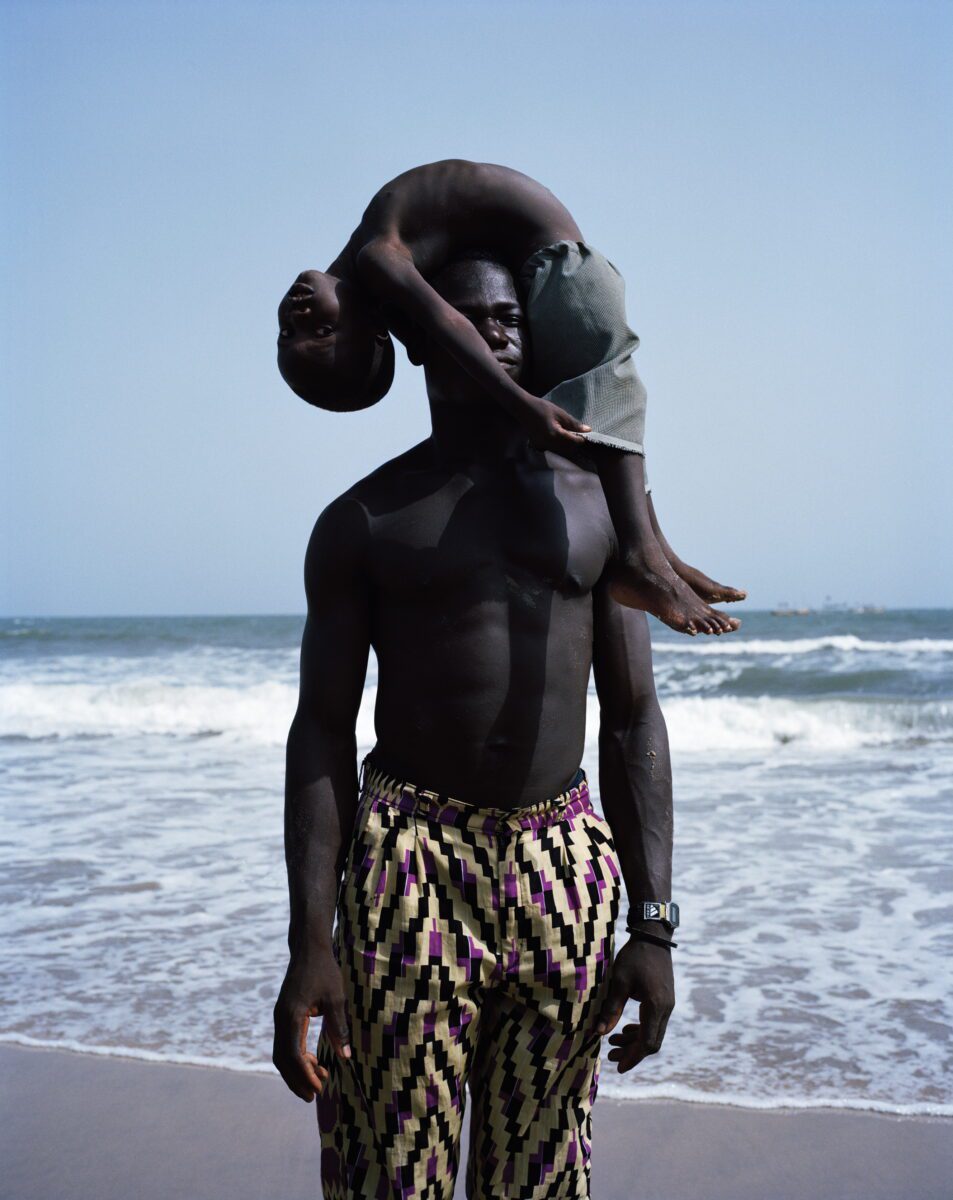

6. D.N.A., 2007 From Flamboya, 2008 © Viviane Sassen (1972).

7. Suzette Bousema, Future Relics 40, 2025 © Suzette Bousema.