If you consider Martin Parr, the word “prolific” doesn’t begin to do justice to the British photographer. An artist compared to everyone from playwright Alan Bennett to seaside postcard artist Donald McGill, he’s been active since the 1980s – when The Last Resort captured the good folk of seaside town New Brighton and propelled him into the public eye. His work has since been shown in over 80 exhibitions globally, while his photographs have been published in over 145 books.

This week sees the cinema release of I Am Martin Parr, an affectionate documentary tribute. “Martin never stops,” says Lee Shulman, the visual artist behind the film. “That was something I really wanted to show. Photography is great, but photography is also about hard work and the good photographers for me are the people that never stop. They spend every day doing their work. And that is Martin. He just doesn’t stop.”

Schulman, who has lived in Paris for 23 years, is sitting with Parr in a hotel in the French capital, as they gently bicker like a long-standing married couple. Now 72, Parr is in cancer recovery and uses a Rollator to get around. “It hasn’t actually stopped me wanting to go out and take pictures,” he explains. “I can’t scramble over rocks anymore and I can’t go for nice country walks, but I’m alive and well so I can’t complain!”

Parr and Shulman first met in 2018 at the Arles Photography Festival, and since collaborated on Déjà View, which paired Parr’s images with amateur photographs discovered between the 1950s and 1980s (Shulman runs The Anonymous Project, an initiative dedicated to collecting and preserving mid-century colour slides). Their friendship was “love at first sight,” jokes Shulman. “My wife used to say, ‘You spend more time with Martin than me!’ Which is still the case!”

Still, it’s not hard to see where his and Parr’s interests dovetail in capturing British iconography. Eschewing the idea of doing a traditional cradle-to-the-grave portrait, Shulman suggested that he and Parr go on a road trip. “It couldn’t be better timing. It was the coronation [of King Charles III]. This was great. Timing is everything in life. So we kidnapped Martin, stuck him in a van and we went around the U.K., and revisited some of the famous and infamous places that he photographed in his books.”

Contributors to the documentary include the likes of Grayson Perry and David Walliams, but the real juice comes from Shulman’s interviews with the mischievous maverick. “I wanted him to tell his story,” says Shulman, who made the choice to only feature audio of Parr’s answers in the film, cut to the footage they filmed across what he calls “the summer of Martin.” “He constantly interviewed me, hoping to get a better take,” groans Parr. “You know how it is with directors! He’d ask the same questions again, hoping the answer is more eloquent than the last one.”

Parr’s work effortlessly captured Britain at its most tragicomic, but it’s not escaped criticism, with some believing that his uncanny eye for photographing working-class Britons was patronising. “When he started and he showed The Last Resort…it was very controversial,” says Shulman. “I mean it was controversial in London, not in the north where he shot the pictures. People were very happy with it. But the institutional world of art was very shocked.” Parr seems not to care a jot. “You’re always an outsider,” he remarks.

The film arrives in an era of Instagram and the iPhone, when the proliferation of digital imagery has arguably diluted the power of the image. But Parr disagrees. “There will always be pictures that rise to the surface. That’s how we remember the world really. It’s easier to remember the world through still images than through film. Like the Vietnam War – you’ve seen all that rolling film but, ultimately, it’s the images from the great photographers that went there that you’ll remember.”

Parr made the transition to shooting on digital years ago and never looked back. “Once you’ve made the jump, there is no going back. And it’s weird to me when all these young people are obsessed with doing analogue photography.” But in a time when everyone is an amateur photographer, armed with a camera-phone in their pocket, there has been a conscious rise in interest in photographers like Parr. So whatever next? A biopic of his life, maybe? But who could play him? “I hadn’t really considered that,” smiles Parr. “You got any ideas?”

I Am Martin Parr is in cinemas now.

Words: James Mottram

Image Credits:

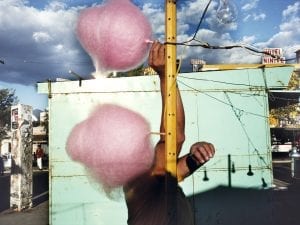

1,3 &5. New Brighton, England, 1983-85. Martin Parr. © Martin Parr / Magnum Photos.

2. Elland, England, 1983-85. Martin Parr. © Martin Parr / Magnum Photos.

4. Wedding at Crimsworth Dean Methodist Chapel, Hebden Bridge Calderdale, 1977. Martin Parr. © Martin Parr / Magnum Photos.