Carrie Mae Weems’ (b. 1953) ethereal photo-portrait The British Museum (2006) embodies many of the larger themes within the current exhibition at Gagosian New York. Curated by Antwaun Sargent (b. 1988), the show presents work by contemporary Black artists who construct and reclaim ideas of physical, personal and cultural space. In the image, Weems faces away from the camera in a black dress, lifted very slightly by the wind towards the grand neoclassical colonnade of the Museum entrance. A group of school children rushes in ahead of her, their small frames emphasising the imposing scale of the Doric columns. Yet the artist remains stationary, as if on the cusp of something unspoken.

The British Museum is a subtle work which arrests the viewer’s attention gradually rather than suddenly. It’s part of a 2006 series, titled Museums, in which the artist is pictured at a range of cultural sites redolent of the Greco-Roman heritage of western history, most of them built during an era of European military expansion and control modelled on the imperium of Rome. Like all of the multimedia artist’s work, including the iconic 1990 photo-sequence The Kitchen Table, Museums is concerned with the spaces that African American and Black people inhabit; whether and on what terms they can call those spaces home, and how these environments are shot through with political and psychological issues – from racism to sexism – which continue to impact lives today.

Sargent’s curatorial focus on “space” is broad enough to incorporate a wide range of uses of the term – from institutional and cultural space to emotional and psychic domains. However, it seems to be the imaginative and literal engagement with public space that forms the most coherent thread across the work on display here, produced by a total of 12 artists. In particular, the exhibition features the first large scale autonomous sculpture by Ghanaian-British architect David Adjaye (b. 1966), whose epoch-defining Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture, unveiled in Washington DC in 2016, brought the design history of West Africa to the US capital.

The three-tiered façade of the Washington structure evokes 20th-century Yoruban craftsmanship, whilst paying homage to the ironwork of enslaved and free African Americans in Louisiana, South Carolina and elsewhere. The architect’s new work, Asaase (2021), created for the Gagosian show, consists of a maze of nested earthen walls climbing to a conical vortex, alluding to the Tiébélé royal complex in Burkina Faso and the walled city of Agadez in Niger, amongst others. The piece indicates Adjaye’s ongoing engagement with the diverse ethnic and cultural origins of West African design – a source of plunder for European artists in the early 20th century – by drawing upon regional motifs associated with leadership and autonomy.

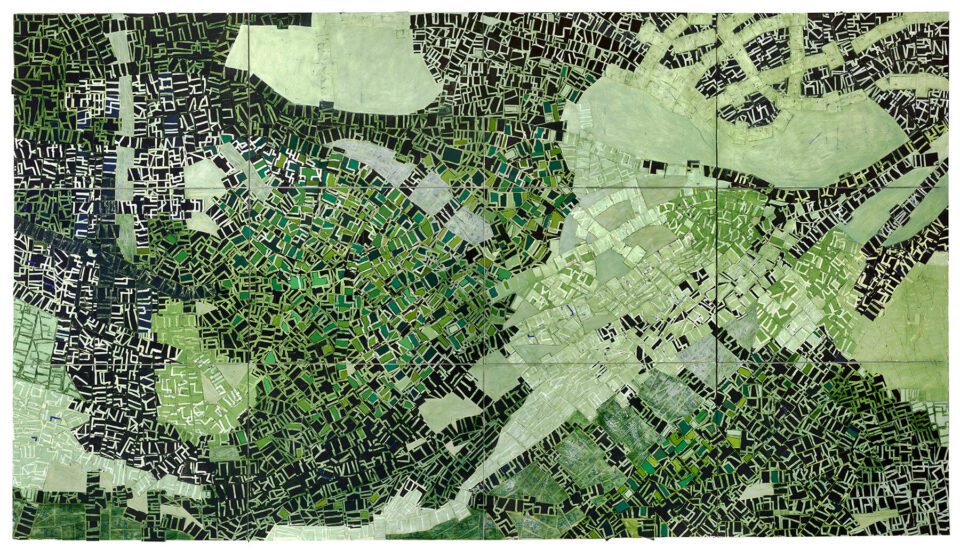

Whereas Adjaye works with space in a literal sense, offering civic structures and sculpture suffused with imagery of emancipation, painter Rick Lowe’s (b. 1961) abstract compositions have a subliminal topographical presence, as if the artist were counter-mapping the urban realms of the US South. That said, the Texas-based artist is perhaps best known for establishing a practice at the boundaries of creative work and community activism. In 1993, Lowe founded Project Row Houses, converting a series of shotgun houses – small domestic residences associated with urban poverty – into studios for artists exploring African-American culture. Since then, the complex has grown to incorporate dozens of properties, providing living and social space as well as creative facilities.

In a new series of canvases for Social Works, Lowe memorialises the 1921 Tulsa, Oklahoma Riots using a loosely cartographical approach, filling his frames with detailed, regular mark-making. These visually dense works reference the prosperous African-American district of Greenwood, Tulsa, known as the Black Wall Street, which was attacked and razed by white supremacists in the early 20th century with the covert support of many city officials, killing 36 and injuring 800. In imaginatively transforming street plans and aerial views of the neighbourhood, Lowe offers a memorial for an environment never allowed to flourish.

Elsewhere in the exhibition we find Theaster Gates’ (b. 1973) mixed-media homage to house DJ Frankie Knuckles, Linda Goode Bryant’s (b. 1949) fauna-based installation referencing her work with urban farming co-op Project EATS and Lauren Halsey’s (b. 1987) Afrofuturist-influenced “box” sculptures, daubed with commercial signage and graffiti. Like Bryant, Titus Kaphar (1976) is a community organiser as well as an artist, whose NXTHVN collective in New Haven Connecticut provides residences, fellowships and professional development opportunities. Alongside his own painting in Social Works, Kaphar has selected works for display by five former NXTHVN Studio Fellows: Zalika Azim (b. 1990), Allana Clarke (b. 1987), Kenturah Davis (b. 1984), Christie Neptune (b. 1986) and Alexandra Smith (b. 1981). Many of these younger names engage with ideas of psychological space and Afro-Surrealist allegory, suggesting that, for a new generation of Black artists, it is perhaps the imaginative frontier that must also be reclaimed.

Social Works runs at Gagosian West 24th Street, New York, until 11 September Find out more here.

Words: Greg Thomas.

Image Credits:

1. Christie Neptune, Untitled (2021).© Christie Neptune. Courtesy of the artist and Grant Wahlquist Gallery, Portland, Maine, and Gagosian.

2. Carrie Mae Weems, The British Museum (2006–). © Carrie Mae Weems. Courtesy of the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York and Gagosian.

3. Rick Lowe, Black Wall Street Journey #5 (2021). © Rick Lowe Studio. Photo: Thomas Dubrock. Courtesy of the artist and Gagosian.