Installations that clear the air, light waves that reflect upon rising sea levels, a net that cleans up space junk: this is the work of Daan Roosegaarde.

Daan Roosegaarde (b. 1979) grew up in the Dutch town of Nieuwkoop. He spent his days roaming in the tranquil countryside surrounded by water, building forts and tree houses. He still taps into that playful sense of idea generation today, whilst tackling some of the most pressing environmental issues of our time. “I’m on a mission for clean air, clean atmosphere and creativity,” he says, building a world of possibilities where solar-powered stones or smart coatings illuminate bike paths and highways, ancient algae light up streets, smog becomes jewellery and space debris turns into fireworks. Roosegaarde’s practice is interdisciplinary. It encompasses art, architecture, design and engineering all at once. Seeking to reverse humankind’s destructive tendencies by rendering the otherwise intangible forces of nature visible, this citizen-artist manages to invite contemplation as well as call for action on a grand scale.

It is with equal measures of idealism and pragmatism that Roosegaarde illustrates the dangers of rising seas in Waterlicht (2016-2018). The work uses LEDs to offer a striking horizontal membrane of blue beams that floats in mid-air, extending over a large space with a swaying, wave-like motion. This virtual flood serves as a potent reminder of how water can both give and take life. Roosegaarde explains: “Experience the vulnerability and power of living with water.” For its initial presentation in Amsterdam, Waterlicht illustrated what would happen if levels rose in the Netherlands, itself an aquatic wonder of sorts that relies heavily on embankments for protection – a quarter of the country lies below sea level and almost 60 per cent of the geography is susceptible to flooding, teetering on the edge of destruction. Ultimately, the land would become inhabitable. This is a truth that, in Roosegaarde’s eyes, should never be forgotten. “Without design and technology, we would drown. At the same time, we’re always trying to live with nature. That kind of balance is in the work I make.”

Waterlicht, as a collective experience, attracted 60,000 people in one night across Amsterdam’s Museum Square. Since then, the installation has travelled to various Dutch cities as well as to some of the largest metropoles worldwide, including Dubai, London, New York and Paris. Roosegaarde may be inspired in part by Romantic ideals from the Dutch Golden Age, but he remains keenly aware of the need to harness nature in order to better live in harmony with organic matter. As such, Waterlicht lends a poetic dimension to tackle a very present, problematic issue.

The installation has a mind of its own, changing along with the natural light or humidity of its surroundings and causing raindrops to appear to float when they hit the blue projections. Whilst the result is aesthetically pleasing, Roosegaarde capitalises on the sense of wonder that the work elicits, banking on people’s attention to offer sustainable solutions. His “landscapes of the future” reflect the concept of “schoonheid” – a Dutch word pointing to both purity and beauty. “That’s where the magic happens. My role is to demonstrate the potential of a new world and not be scared but be curious.” Roosegaarde’s new monograph, available from Phaidon, is an invitation into a world of intrigue.

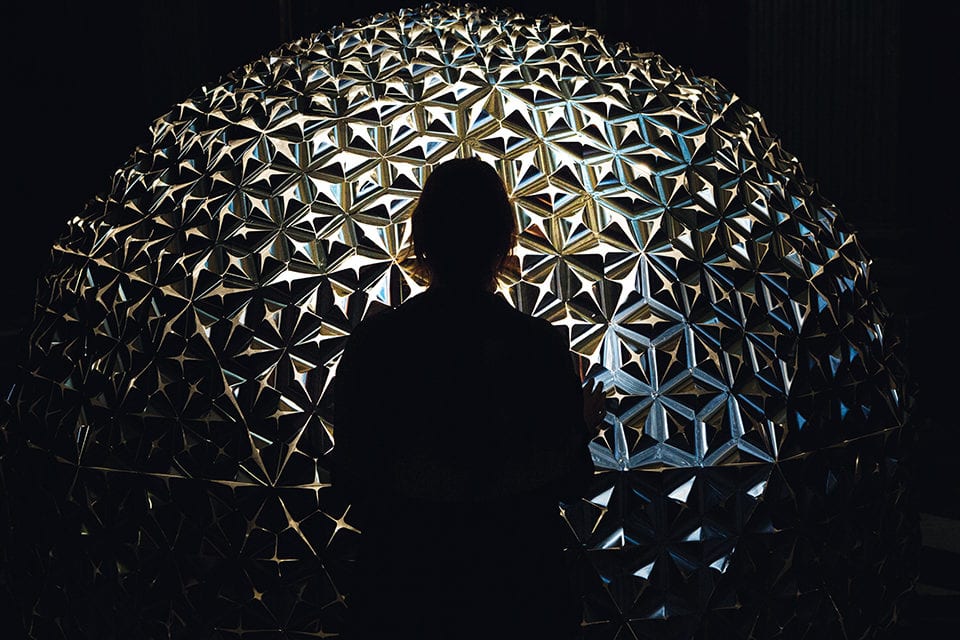

The title produces a sense of wonder, starting with early works that question the possibilities of the digital age. Many of these examples were largely indoors and focused on technology as both concept and medium. First realised in 2006, Dune, for example, features a techno-natural topography of cattail-like fibres which light up and emit sounds when “welcoming” approaching visitors. Hundreds of them are strewn like blades of grass or underwater worlds. The pole-like sculptures also react to speech with noises and movements. Similarly, when Lotus Dome (2010) was installed inside the 17th century Sainte-Marie-Madeleine church in Lille, it presented an overwhelming vision. Mimicking a lotus flower, the silver structure “bloomed.” Hundreds of smart foils – which covered the surface – unfolded organically in response to the heat of a visitor’s hand.

After these experiments, Roosegaarde gradually shifted to increasingly large-scale assignments where technology was used as a mechanism for social innovation, achieving specific results, or more precisely, responses, in urban spaces. To reduce the deadly air pollution that plagues many major cities, he sought to build “environments that can heal us” with a Smog Free Tower (2015-present) that cleans the air in public spaces. Having been situated in the likes of Beijing, Tianjin and Rotterdam, the seven-metre aluminium tower uses only 1,170 watts of green energy and positive ionisation. It can clean up to 30,000 cubic metres of air per hour and the area around the structure becomes 20 to 70 per cent cleaner than the rest of the city. At an installation in Kraków, small dogs could smell the fresh air from afar, abandoned their owners and rushed toward the tower. Rabbits crowded at the Rotterdam site. “If nature can sense what is good for them, why can’t humans?” Roosegaarde asked. Couples have proposed or gotten married with Smog Free Rings made from compressed smog particles collected by the tower. Each purchase contributes some 1,000 cubic meters of clean air to a city. In another spin-off, bicycles have been designed to absorb polluted air, cleaning and distributing it back to the cyclist as they ride around the landscape – as tourists or commuters.

At 39 (turning 40 this July), Roosegaarde has churned out a lifetime’s worth of projects – nearly half of which have been self-commissioned. Now, he is looking at the potential of anticipated or actual human interactions. This is the basis for a range of new tasks for those in his eponymous studio, where a mingling of engineers, architects and scientists push the boundaries of what those respective disciplines consider possible. “It’s sort of a West Side Story of two gangs who don’t belong to each other but have this common love to create, to perform, to engage and to explore.” The pieces often take years to develop, with the artist ready to acknowledge that it’s challenging at first to know an idea is a good one, something that at first is just “like a taste in your mouth.” His team spent two years harnessing the unique properties of bioluminescent algae – some of the oldest micro-organisms – that will produce prolonged natural light when touched in the right conditions. Polymer shells filled with the algae illuminate when they are touched in Glowing Nature. Roosegaarde, who is eager to find functional applications for research, is now developing blueprints to use the plant for self-sustaining, responsive street lamps.

Glowing Nature was first presented in 2017-2018 as part of Icoon Afsluitdijk, an innovation programme commissioned by the Dutch government along with two other projects: Gates of Light and Windvogel. The latter involves “smart” energy-generating kites that can supply up to 200 households thanks to the push and pull of their cables connected to a ground station. The specially produced fibre lines emit a green light. It composes a visual symphony in the night sky in one of many efforts to show the beauty of green energy. “I’ve always had a fascination for technology and science, but it’s about the people and their interactions, like with Gates of Light. It’s both functional and fancy at the same time,” he said. The largest of the three commissions, it is conceptual on a massive scale. Permanently lining the 32-kilometre Afsluitdijk Dam, the work draws attention to the 60 soaring concrete floodgates. Lines made of reflective material surround the structures, originally produced by Dirk Roosenburg in 1929, the grandfather of architect Rem Koolhaas. Headlights from passing cars cause the lines to shine brightly, underscoring the huge slabs of concrete that protect the land and – in extension – people’s lives.

In a tribute to Vincent van Gogh, a bicycle route connecting the town of Nuenen – where he lived from 1883 to 1885 – to Eindhoven glimmers at night with countless small stones covered in a unique phosphorescent coating. Ripples and swirls of light recall one of the artist’s best-known works: The Starry Night (1889). The installation also serves as a public safety function. In collaboration with construction engineering company Heijmans, Roosegaarde uses similar techniques to develop smart roads whose traffic lanes harvest solar energy during the daytime and illuminate at night for eight hours without any additional source of energy.

In his most ambitious project yet, Roosegaarde is turning to the universe. Space Waste Lab, a collaboration with the European Space Agency, looks at capturing the more than 29,000 little pieces of broken rockets and satellites floating around the Earth. These bits of debris can damage existing satellites and disrupt digital communications. In extension to their technological problems, visually the junk looks like the paint splatter of a Jackson Pollock. This is taking the monumental to another level: “There’s not a lack of money or technology in this world, but perhaps a lack of imagination.” The floating junk has since been identified with large LED-powered beams that use real-time tracking information. The plan is to capture the shards with a net and drag them to Earth, where they will burn when hitting the planet’s atmosphere and, in the process, eject an astronomical display of “shooting stars.” It is set to be premiered at Dubai World Expo 2020 or the Netherlands’ Floriade 2022. In the offing are plans to use the debris for 3D printing of future moon habitats and even to build a giant sun reflector that would help reduce the climate crisis.

We live in a geological epoch defined by humankind’s negative impact on the environment – the Anthropocene. It is in such a moment of vast, near irreversible change that Roosegaarde’s vision is much more optimistic and completely necessary. It’s one where human beings are a small part of deep time with the potential to leave the environment a better place. That’s no small feat, and one that requires an uncanny amount of creativity, something he calls the “true capital” that distinguishes man from machine. “It’s obvious that we need to change. We do this for two reasons – out of love or out of fear. We can scare people with numbers or doomsday scenarios, some of which are really true, but my job is to generate interest in the future.”

Olivia Hampton

Daan Roosegaarde is published by Phaidon. www.phaidon.com | www.studioroosegaarde.net

Lead image: Daan Roosegaarde, Waterlicht, 2015 – present.

Artwork © Daan Roosegaarde.