Roosmarijn Pallandt discusses her COP26 sound sculpture

The word “photosynthesis” has Greek roots – literally translating as “a putting together of light.” The process first produced oxygen of billions of years ago and keeps it there today. Photosynthesis is essential to life as we know it, and is one of many intrinsic connections between organisms.

Amsterdam-based Roosmarijn Pallandt is a transdisciplinary artist interested in the interdependence of living things. To develop her practice – which spans sound, 16mm film, analog photography and textiles – she has travelled to remote regions, spending time with and learning from nomadic peoples. Her work originates from Indigenous cosmologies, co-operations with plant life, ecological encounters and quantum physics. Pallandt recently presented an audio sculpture at the COP26 summit on climate change in Glasgow. Titled Light Sounds Air, it filled the space with the frequencies of pulsing root systems and photosynthesising aquatic plants. The aim: to draw attention to the regenerative nature of life on earth.

A: Where did your ideas for Light Sounds Air begin, and how did you begin planning the piece?

RP: I was commissioned by the Bonn Sustainable AI Lab to create an artwork hosted by the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change for COP26 in Glasgow. My initial idea was to open all windows of the conference and simply let the weather in. I Imagined the strong Scottish winds being present for a single moment during the discussions and meetings. In the end, that idea didn’t seem impactful enough, but I did like the idea of creating a piece that didn’t need much and that would work within audiences’ imaginations. I decided to focus on light and air.

Together with a local composer, Patrick Farmer, I made a sound sculpture composed of sound vibrations by plants and trees as they pull carbon dioxide out of the atmosphere, Light Sounds Air celebrates the biochemical miracle of photosynthesis – literally meaning “a putting together of light”. It alludes to the collective power of imagination, and the possibility of re-evaluating our place in a much larger universe.

The location was the two main conference rooms where, each day, world leaders would convene. Every night, after the delegations have left, the entire conference space – empty and absent of humans – was immersed in a sound sculpture. The piece was composed of the amplified sounds of vibrations by plants and trees as they pull CO2 out of the atmosphere, transforming light into oxygen. In this way, the artwork resonates with nature’s creative life-giving frequencies, making us aware of the continuous regenerative movement of intelligent systems.

A: The piece filled the conference space with amplified sounds of “vibrations by plants and trees as they pull CO2 out of the atmosphere.” Where did you gather the sound clips for the piece?

RP: All of the sounds were gathered in UK ponds and forests miles away from the conference centre. It was important to me that the sounds were all recorded in the UK. To get the field recordings, I collaborated with Dolphin Ear Global Microphones and composer Patrick Farmer.

A: How important was the geography for the source material?

RP: Light is key to photosynthesis, and ultimately forms the piece. So, the weather was an important factor. Yet it was the dramaturgy that had my main focus. The gesture, the placement and the resonance within this given setting were all essential to me.

A: In what ways does your sculpture tap into an anti-anthropocentric stance – favouring a symphony of sounds as an ecosystem, rather than one, singular voice?

RP: The work emphasises an ecosystem of vibrations and pulsations within plants. These are balanced through myriad relationships, constantly adjusting in resonance with others. The frequencies of our environment affect us as we live inside in them – it’s a dynamic interaction.

A: In what ways might sound, as opposed to visuals, be best suited to tackling the climate crisis? We exist in an age of over-saturation and image dissemination, which has done little to persuade us of the catastrophe laid out ahead of us. What, inherently, does sound offer audiences?

RP: We live in an age where, whilst some of our senses are oversaturated, others are deprived. The sounds within my recent work lie beyond the domain of our hearing. They are an invitation to expand our relationship with the sensory elements of the world – noticing our environment as a whole.

A: How does this work compare to some of your previous pieces?

RP: For nearly 12 years, I have been travelling to various corners of the world where I meet with communities who form harmonic relationships with their environments. Many of these peoples have a strong belief in the spiritual essence of their surroundings and permit the elements to dictate their pace of life. Some communities engage in rituals, songs, prayers and chants which constantly change in a harmonious rhythm orchestrated by their surroundings. The woven tree bark textiles from the series A-un, for example, document modulating pulses over time – giving rise to different spatial forms, textures and densities. There might be an immediate connection between all places and moments as universal modes of invisible waves.

A: Tell us briefly about the exhibition in Mexico City, Index 5: Estancias.

RP: Index 5 Estancias was an exhibition with Daniel Buren, Adrian Burns, Enrique Ježik, Perla Krauze, Francisco Larios, Daniel Lezama, Gabriel O’Shea and myself. I exhibited a series ‘Spell for the river Rapid’ based on song by a Japanese shaman, who follows the pulling of the tides, the rise and fall with her voice.

A: What do you have planned for 2022 and beyond?

RP: I am currently researching sounds influenced by measures that we can neither hear or see, but that we can respond to. These include harmonic vibration patterns, ultra-low frequencies and metabolism as way to perceive time. In recent months, and during the pandemic, I have been drawn to volcanic islands, where I am collaborating with researchers, microbiologists and a musician on a composition for the cello, based on 20 years of seismographic data input. Meanwhile, I’ve been working on an artist book based on my interest in, encounters and collaborations with native Shamanism across various Japanese islands over the past 8 years. At the start of February, I will be exhibiting works at the ZONA MACO art fair in Mexico City with my gallery Hilario Galguera.

galeriahilariogalguera.com | roosmarijnpallandt.com

Image Credits:

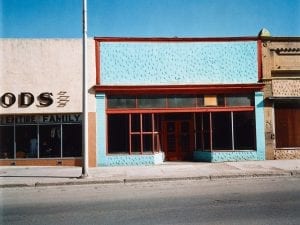

1. N07_1_3, 2019, Platinum Print on Japanese Gampi. © Courtesy of Galería Hilario Galguera, photo: Studio Image Credits: 1. N07_1_3, 2019, Platinum Print on Japanese Gampi. © Courtesy of Galería Hilario Galguera.

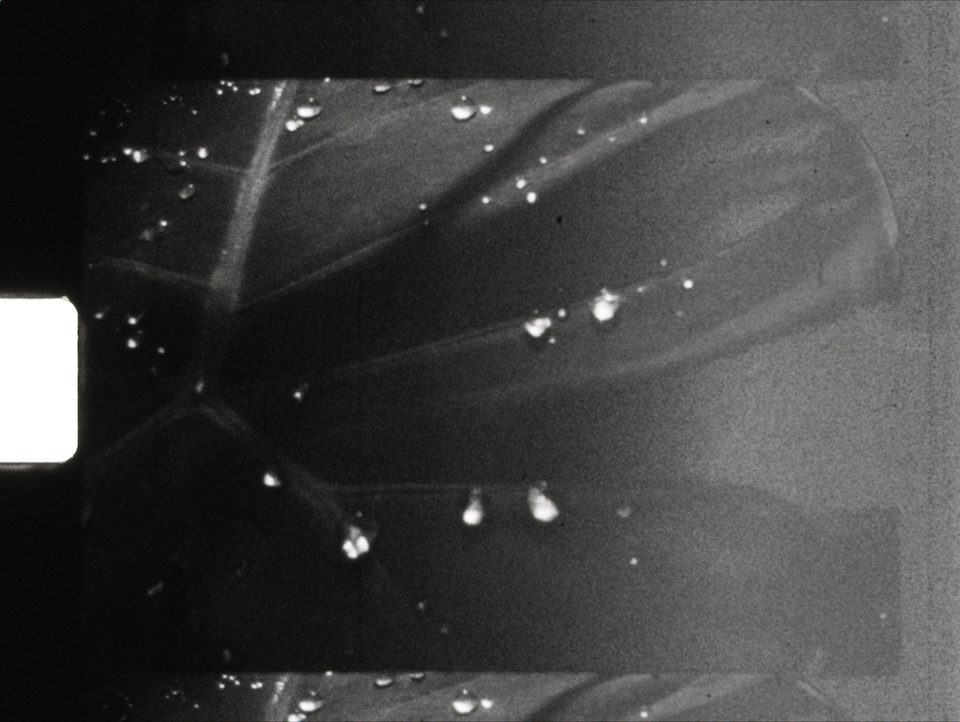

2. Still from Untitled (2021). Super 8, silent, solarized on the pattern of sound. Roosmarijn Pallandt

3. Still from Untitled (2021). Super 8, silent, solarized on the pattern of sound. Roosmarijn Pallandt

4. Portrait, Roosmarijn Pallandt. © Courtesy of Galería Hilario Galguera, photo: Yamandu Roos.