Barbara Kasten has been making boundary-breaking experiential art for over five decades. Her constantly evolving practice incorporates a diverse range of mediums, with the interplay of light and perception at its core. Aesthetica speaks to the artist about materiality, abstraction and creative perseverance in line with a new show at Kunstmuseum Wolfsburg.

A: Works is your first ever European museum show. Is this a big moment for you?

BK: I’ve always been identified as a photographer, but I don’t accept that label. I really want people to see that I have worked across many different disciplines, and not just relied on the photograph to express myself. The show at Kuntsmueum Wolfburg is a survey rather than a retrospective. Anybody who sees it will experience examples of the work through the years, but the complete picture is still out there. I’ve also created a new sculpture, which is made from metal forms that the gallery uses to build walls and delineate space. When I saw them, I thought they were really interesting as objects and that’s what I try to do: to use a material in a way that it’s not intended. The piece is almost like a Vladimir Tatlin sculpture, it’s very high with a metal structure and inserted panels of colour plexi glass so that the light filters through and creates a pattern on the floor which is a photogram.

A: When did you first become interested in photography and more specifically, photograms?

BK: The photogram – which merges materiality and light – intrigued me after I first became aware in the 1970s of [László] Moholy Nagy’s experiments. This combination has been the focus of my practice ever since. I am concerned with recording the imperceptible and unusual relationship of objects which can be transformed by light. To me [photography] is essentially a medium to record – because photography needs a subject– but I’m more interested in how it can capture a moment.

For me, it’s all about perception – how materials interact with light. It’s about finding a moment where the light does something that we wouldn’t and couldn’t notice. Take, for instance, the colour shadows that feature in a lot of my works. If I didn’t have the light on that grouping of objects you wouldn’t see those shadows, which become an experience where two things play against each other. It’s no longer an object with a shadow because the shadow has as much to say about the composition as the object.

A: For your series Architectural Sites, you built “stages” to transform existing buildings such as the World Financial Centre and the Whitney Museum of American Art. Where did this idea come from?

BK: The concept evolved from my work in the studio where I created constructions in front of the camera. I used geometric mirrors to incorporate surrounding perspectives. I use a large format analogue view camera that is stationary – unlike a handheld camera that allows a photographer to move around the subject to find alternative views.

I grew up in Chicago – a city renowned for its architecture. When I was offered the opportunity to document Post-Modern buildings in New York for an article in Vanity Fair, I moved from the studio set to real, enormous settings of famous architecture. This provided a huge change in scale, and a challenge in creating a movie-like production. It was extremely satisfying that I continued the project on my own with museums in California and Atlanta.

A: Do you generally have a composition in mind when you’re creating, or do you assemble the pieces and see what arises?

BK: Normally, my interest is in material and its properties, so there’s a lot of controlling and experimentation. It’s a very fluid, intuitive process of working. It’s like I’m doing something in order to then cancel it out. I’m building something that looks like an object, but I don’t want it to look like an object, so I cancel it out when the light hits and the shadows create other fleeting subjects. The shadows are like building blocks – but they’re not there so it creates a contrast between the real and the unreal. People also call my work “otherworldly” – but it’s not really that.

A: It feels like your work operates within an in-between space?

BK: And that’s exactly where I want it to be – not defining anything – but creating a new moment: a new experience, a new perception. I think of it as a political tool because it can open people’s minds to something that isn’t concrete. An abstraction challenges the way you see and defies pre-conceived notions.

A: Are you afraid of failure?

BK: People think that art making comes from some sort of gift from above. In some ways, it is a gift, because you need a unique kind of perseverance. Failure is part of the process. You don’t give up, you don’t just say ‘okay this is not working’ and forget it – you keep bending and moving and working in a direction. For me, that’s not towards a pre-conceived sketch or idea, although there might be some sort of directional mode. I just completed a design for a 60-foot-long public art mural. I’ve never done anything that long and I’ve never made a public artwork, so the process was unique for me. That kind of thing makes me rethink everything. The process is the most important thing.

A: Are you in the studio every day?

BK: Every single day. But it’s not like you go to the studio and you’re constantly creating a work of art, you go to the studio for the environment, the ambience, the mindset of being in a workplace and having my work around me, being able to see it as I walk by. It is a different experience to sitting in front of a painting, but that also needs to happen, you need to put time into examining not only your own work but other works. People spend seconds in front of a work of art, but if you really want to examine a painting, a sculpture, anything that you see in a museum, you really should sit in front of it and spend time looking at it because it changes the more attention that you pay to it.

A: Do you think that communication is somehow essential to your creative process?

BK:The goal is not to communicate per se, but to sort of reveal your inner self and when it’s out there, maybe someone else can identify with even just a fraction of what you’re trying to do. You’re always going to have people who criticise what you do, or don’t understand what you do. They might not even want to understand what you do because it might conflict with some of their own ideas. That’s why art is always the first thing any dictatorial environment wants to suppress. We – as artists – are a threat to anybody who wants to control the way people think.

Millie Walton

For more information about the show at Kuntsmuseum Wolfsburg, click here.

Credits:

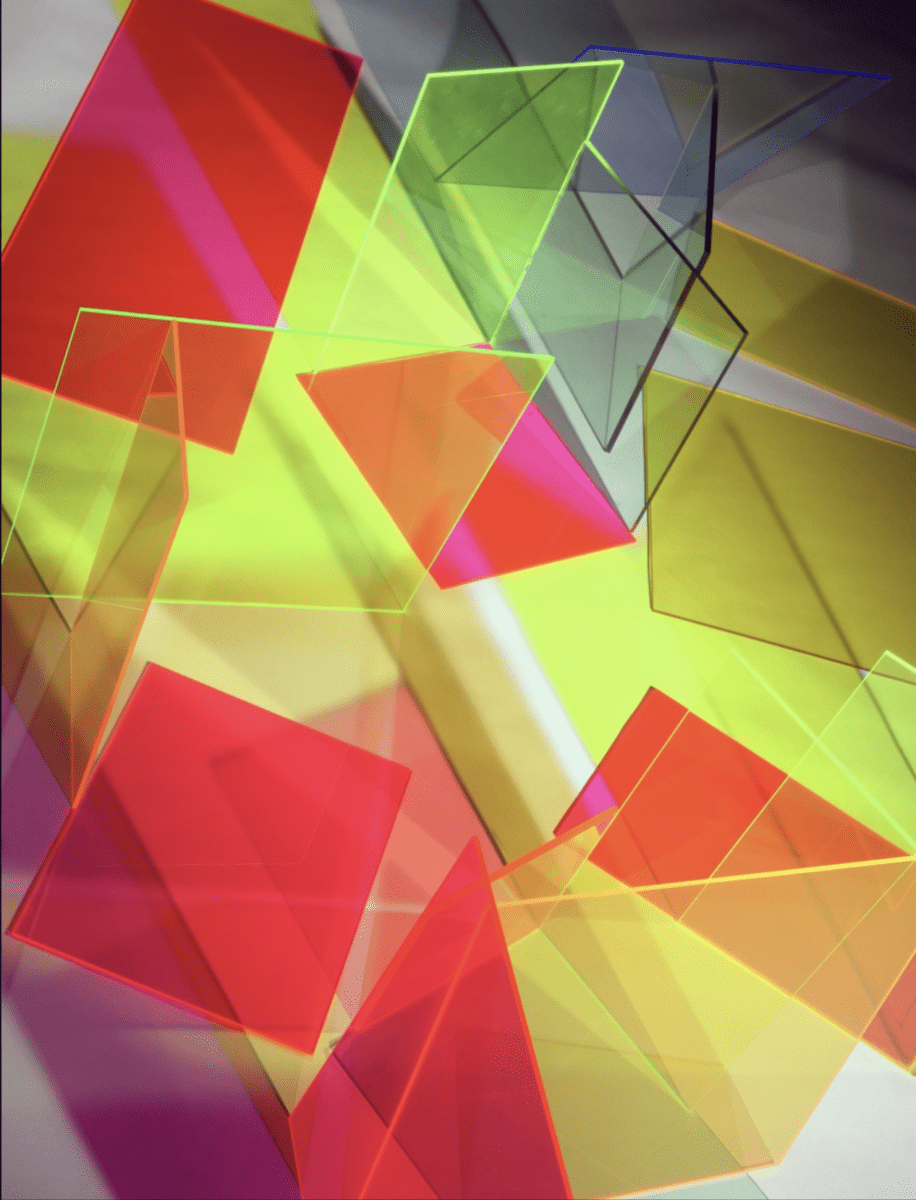

1. Barbara Kasten, Architectural Site 8, December 21, 1986, Cibachrome © Barbara Kasten, Courtesy the artist.

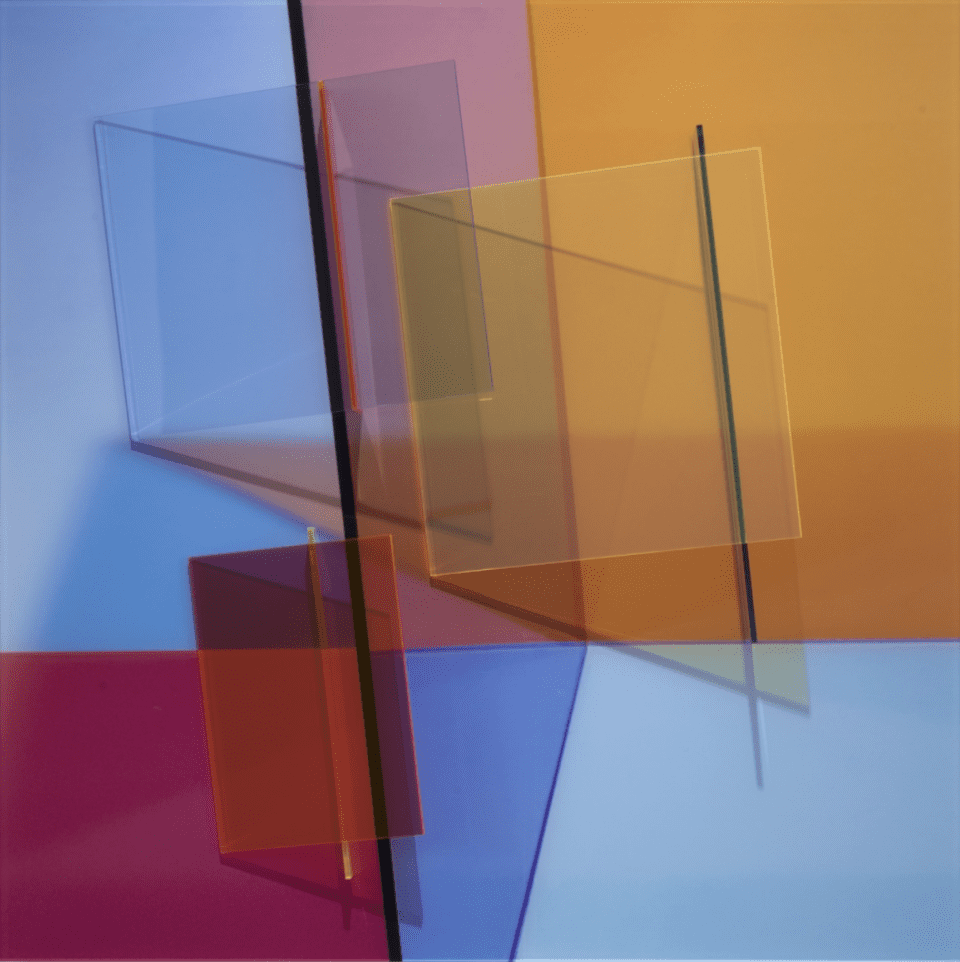

2.Barbara Kasten, Collision 5 T, 2016, Digital Chromogenic Print © Barbara Kasten, Courtesy die Künstlerin, Bortolami, New York, Kadel Willborn Gallery, Düsseldorf und Thomas Dane Gallery, London.

3.Barbara Kasten, Triptych I, 1983, Polaroid Polacolor, Collection Monika Schneetkamp © Barbara Kasten, Courtesy the artist and Kadel Willborn, Düsseldorf.

4. Barbara Kasten, Progression One, 2017, Digital Chromogenic Print, fluorescent plexiglass © Barbara Kasten, Courtesy the artist and Bortolami Gallery, New York