Breathing is political. Over seven million people die each year from the effects of air pollution, with 91% of the world’s population living in places where outdoor air quality exceeds WHO guideline limits. 8.43 million premature deaths are attributed to it annually, making the air we breathe the largest environmental threat to human health worldwide. In this context, the statement “I can’t breathe” has immense resonance. It’s also a keystone of the Black Lives Matter movement, originating from 2014 and the last words of Eric Garner, a 43-year-old unarmed Black man who was killed after being unlawfully arrested and put in a choke hold by a New York City police officer. These words have been uttered by far too many unarmed Black Americans facing similar fates at the hands of law enforcement. Following the death of George Floyd in May 2020, the phrase became widely known, roaring across the world amidst enormous protests; it carries a grotesquely long history of marginalising carceral systems.

In 2024, breathing remains a contested battleground. Today, as Israeli occupation and genocide rages on in Palestine, “I can’t breathe” is an ongoing plea. As one instance: the 77-year-old renowned Palestinian painter Fathi Ghaben recently passed away in Gaza after being denied permission to leave the region to seek medical treatment abroad for chest and lung illness. A few days prior to his death, a relative of Ghaben’s uploaded a video to Facebook in which Ghaben, clearly sick, makes repeated pleas of wanting to breathe. The video was an attempt to build pressure for him to be able to leave for treatment in Egypt, given that Israeli airstrikes had incapacitated the Palestinian healthcare system. Ghaben’s condition had deteriorated from increased smoke inhalation due to the bombardments. In the end, absolutely nothing was done. Sadly, Ghaben passed away on 25 February 2024.

Now, the Irish Museum of Modern Art (IMMA) makes breathing the curatorial focus of a major new exhibition. The artist lineup for Take a Breath, and its accompanying programme, is mammoth: luminaries like Ana Mendieta, Hajra Waheed, Khadija Saye, Lawrence Abu Hamdan, Marina Abramovic and Pamela Singh have works on display. Each piece treats the act of respiration as a nexus of intersecting conditions – being human, of course, with breath being the signal of life; sociopolitical factors that determine air quality and access; the state of the climate; and wider post-colonial and political situations affecting who has the right to breathe freely, or not.

In Take a Breath, multimedia artist, scholar and writer Belinda Kazeem-Kamiński (b. 1980) tenderly approaches these brutal politics through Respire (Liverpool) (2023), a film that “references the precarity of Black breathing and proposes breath as a means of individual and collective liberation.” Previously shown at the 2023 Liverpool Biennial, curated by Khanyisile Mbongwa, the work shows Black people from the region, all of different ages and genders, blowing into a bright red balloon. A soundtrack made by Kazeem-Kamiński and Bassano Bonelli Bassano, a frequent collaborator, plays in the background. It’s a slower, mellower rendition of Keep On Keeping On (1971) by American singer-songwriter Curtis Mayfield; this version leaves more room for the sound of wind and, of course, breathing. Some listeners hear the ocean. “It’s quite a journey, starting high up and, then, in the wake of the piece, the sound goes down. You can really feel it in your body; the sound reverberating.” The viewing experience is entire, with the film activating all the senses. Each breath you take feels more pronounced, and one’s heart rate may regulate in tune with the song’s peaks and valleys. We’re introduced to a gently controlled, artistic modulation of what it means to experience your body and to be in the moment.

“The whole piece is around this idea of Black breath being precarious,” Kazeem-Kamiński elucidates. “When people first hear about Black breath, they might ask: ‘What does it mean, Black breath? Like, is Black breath different than white breath?’ But, when we start to speak about Black Lives Matter – and a quote like ‘I can’t breathe’ – we quickly realise that it has another dimension.” The song Keep On Keeping On was selected, in part, as a metaphor for how Kazeem-Kamiński sees Blackness: as perseverance, continuity and resilience “despite it all.” Here, respiration is at once a gateway to peace and pleasure, and also a “somatic, bodily response to violence.” The pushing of air in and out of our lungs is, at its foundation, merely a mechanism. Yet, it represents a spectrum between “catastrophe and aliveness.” In this film, it becomes an instrument, constantly toeing, testing and measuring the line in-between life, death, freedom and oppression.

Kazeem-Kamiński’s body of work is undergirded by Black feminist theory and the influence of being taught by renowned literature and Black studies scholar Christina Sharpe. It’s also informed by authors Octavia E. Butler and Fatima El-Tayeb, as well as artists Otobong Nkanga and Yinka Shonibare – her “first art love.” For Kazeem-Kamiński, the present is “of an everlasting colonial past: a past without closure.” As a result, she is fixated on exploring the concept of the gaze, and what it is to see or be seen. “Whenever we look at something or someone, we think we know something about them, which, in turn, means we start to categorise, group and objectify whatever, or whoever, it is we encounter. I want to show how this is not an innocent act. There’s a lot of power at play.”

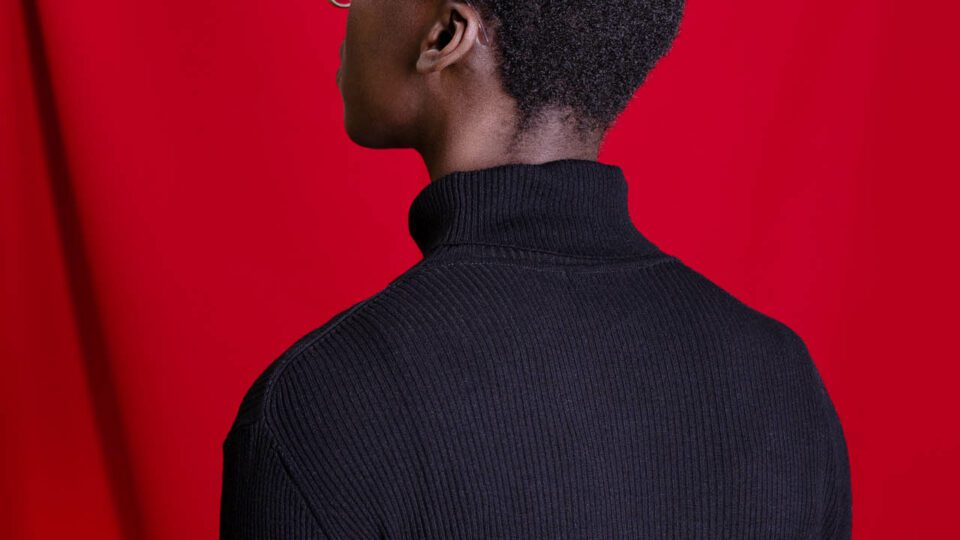

This idea is a common critique of the colonial origins of anthropology, and it shines through in Kazeem-Kamiński’s photographic series In Search of Red, Black and Green (2021). The subject of this triptych looks beyond the frame and away from our eye line. They are always shown in the exact same position, the only difference being the colour of the backgrounds: red, black and green. The combination is a callback to the many flags of African nation-states, which were established post-colonisation and post-independence. “The three equal horizontal bands, going from top to bottom, constitute the tricolour flag variously referred to as the Pan-African flag, the Black Liberation flag and the African American flag – multiple names for one symbol of the liberation of Black people.” Here, colour, subject and gaze come together to connote post-colonial freedom and the Saidiya Hartman-coined “incomplete project” of liberatory resistance amongst the Black diaspora and elsewhere. The three shades are also present in the flags of many Arab states, including Palestine.

Today, Kazeem-Kamiński is represented by Wonnerth-Dejaco Gallery, Vienna. But she took a non-traditional route to get there. “I was always interested in art, and I always wrote around this context, but I never did visual work myself. I made my first series in 2013; it was about childhood memories and growing up as a woman of colour in the German speaking context. You can see that I come from research and theory in this first project, because I was just asking people for childhood memories.” Her practice remains investigative, research-based and process-oriented, exploring the gaps in public archives and filling voids in their collections. Still, Kazeem-Kamiński’s practice defies categorisation. “I’m not an historian … that’s not what I’m really interested in. I want to bring marginalised viewpoints right into mainstream society.”

The artist studied International Development, focusing on theory, museology and post-colonial studies. This comes through in Unearthing. In Conversation (2017), about Austro-Czech missionary, writer and ethnographer Paul Schebesta (1887-1967). The film deals with the violent history of archival material and the trauma of colonisation. “I stumbled across a photograph that shows him and an African man. I asked myself: how is it possible to speak about the violence I see here, without reproducing it?” Yet, Kazeem-Kamiński is clear that, sometimes, this can’t be done. “The video is about what it means to not succeed, because there is nothing you can do to make this violence go away. But that’s the work: finding connections between here and there, then and now … understanding what these people and events mean to us.”

Other artists in Take a Breath echo the themes of Respire and branch elsewhere. Turner Prize-winner Lawrence Abu Hamdan is exhibiting Air Conditioning (2022), which looks at the Lebanese airspace over 15 years, tracking instances of interruption, surveillance and violation, specifically by Israeli aircraft. It’s a work in conversation with the concept of “slow violence”, coined by Rob Nixon in his 2011 book Slow Violence and the Environmentalism of the Poor, which investigates the damage caused by long-term environmental degradation, pollution and environmental racism. There are also pieces engaging with the Anthropocene and Indigeneity.

One of the most famous works on view is Ana Mendieta’s Burial Pyramid (1974), which addresses the body’s relationship to nature. Inhalation and exhalation play a significant role here, as the Earth moves with Mendieta as she breathes. We’re reminded of the growing interest in breathwork as a tool for mindfulness; it encompasses various practices and techniques of controlling, slowing and manipulating one’s breath. For some, the words “just breathe” have become cliché, but the subject remains a focal point for researchers looking into how to alleviate symptoms of stress or anxiety.

The entire viewing experience of Take a Breath is designed to mirror this sentiment. The final chapter of the show allows its audiences to pause, spend time reflecting – and even meditating – in response to the artwork they have just encountered. It’s a considerate curatorial method that takes care of its viewers. Moreover, it offers a moment for the themes and concepts to sink in. Rather than swiftly moving on to the next part of our day, we’re encouraged to digest what we have seen. This strategy is slowly appearing elsewhere. Acts of Creation: On Art and Motherhood at Bristol’s Arnolfini, curated by Hettie Judah, included yoga mats and a colouring and play area for children and mothers. There was also a relaxation and leisure space to draw, sit down and read.

Experiencing art in large institutional exhibitions, especially those which tackle complex and immediate issues, can be intensely overwhelming. As Kazeem-Kamiński’s Respire demonstrates, our bodies can be victims of somatic violence. Our breathing might quicken; we can leave a show not rejuvenated, but drained. It is heartening to see Take a Breath move towards compassionate curation, providing a blueprint for how big topics can be tackled in a mindful yet affecting way.

ake a Breath | IMMA, Dublin | 14 June – 17 March

belindakazeem.com

Words: Vamika Sinha

Image credits:

1., 2., 4.,6. © Belinda Kazeem-Kamiński, In Search of Red, Black, and Green, (2021). 3-C prints on paper, each 80 x 119.3 cm.

3. & 5. © Belinda Kazeem-Kamiński, Unearthing. In Conversation (2017), video, color + sound, 13 min.