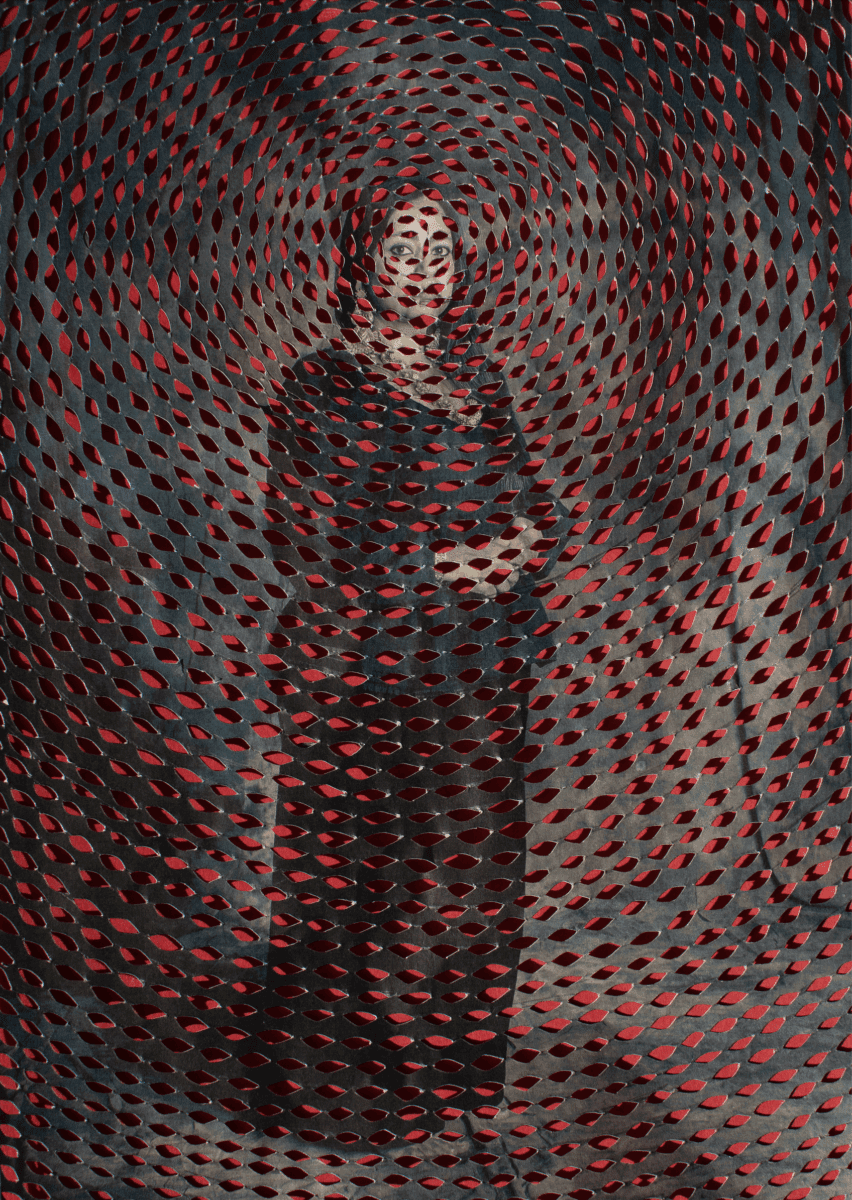

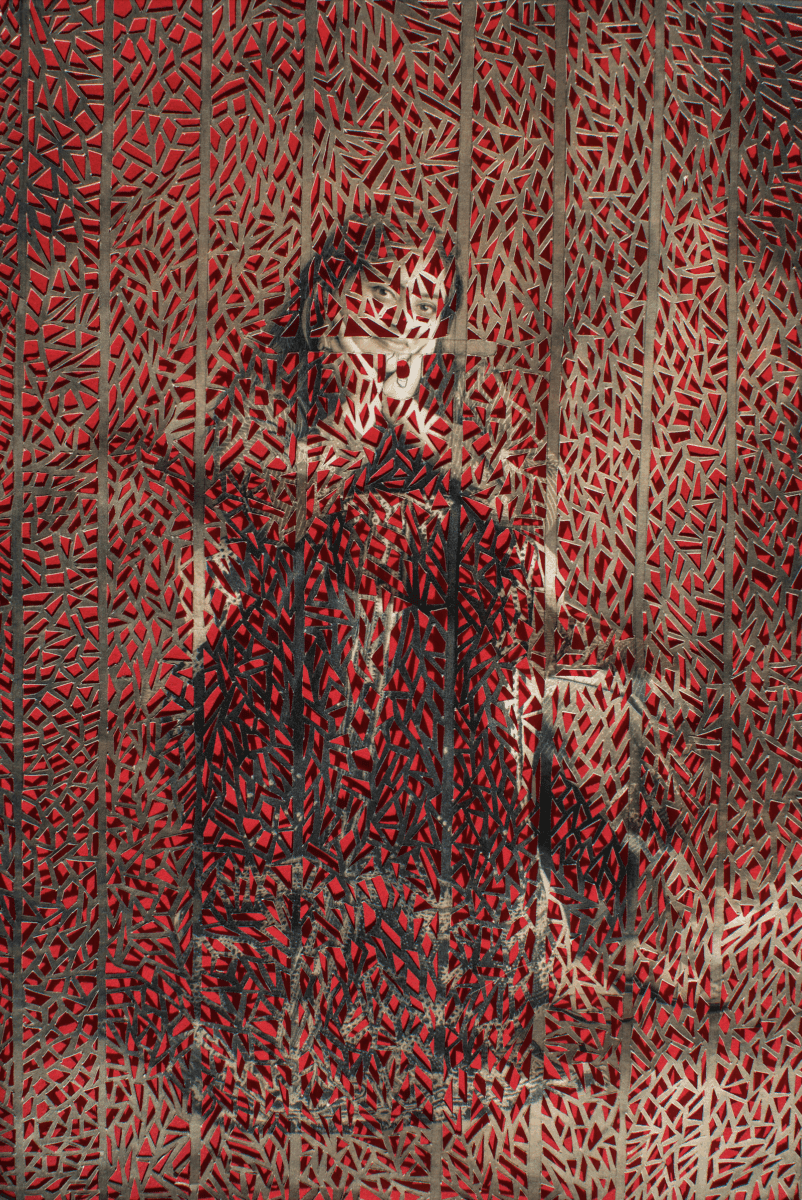

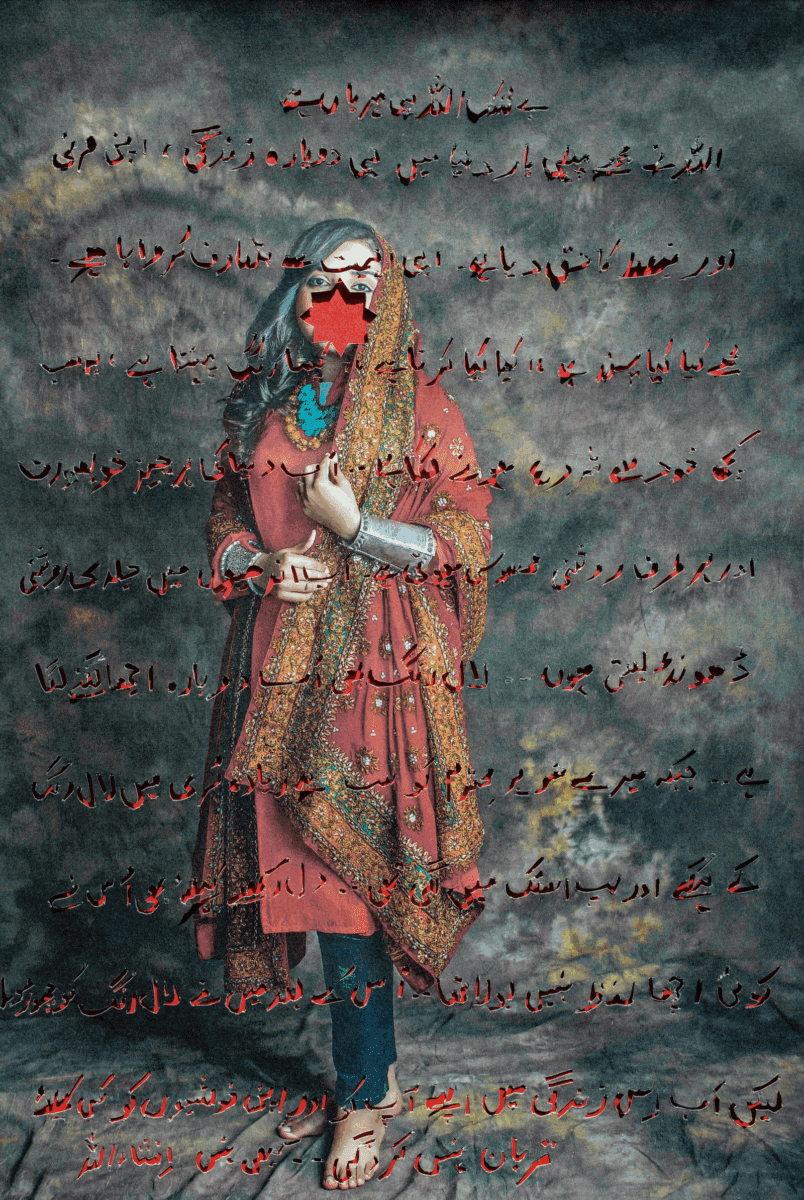

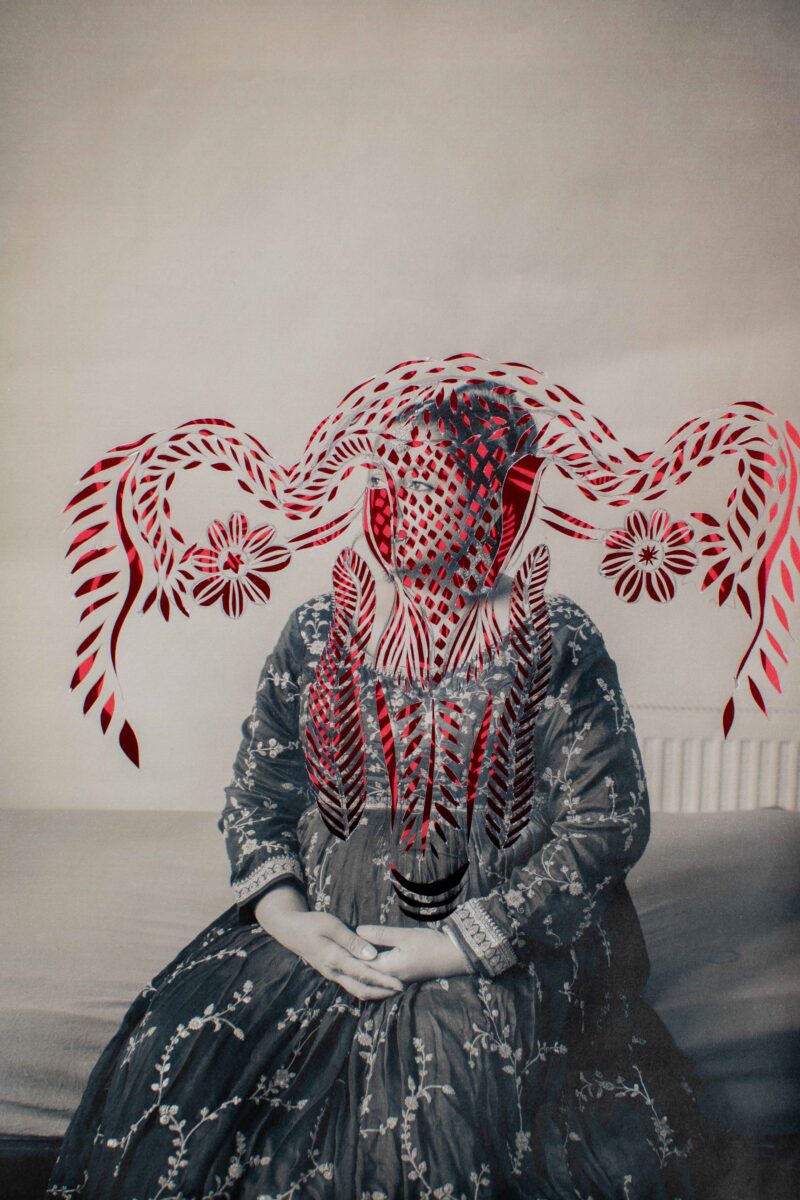

There was an ancient form of torture used in Asian countries called “Lingchi.” The literal translation is “death by a thousand cuts.” The concept forms the basis of a deeply moving series from artist Sujata Setia. A Thousand Cuts is based on in-depth interviews with South Asian women who have experienced domestic violence. The subjects shared their personal experiences, working in collaboration with Setia to create an image they felt reflected their identity. The pictures are printed on fragile A4 paper before being cut in elaborate patterns, revealing vivid red below. It is process that simultaneously reflects how abuse can chip away at a person’s self-esteem, whilst also representing a process of reclamation and agency. Setia’s work has recently been announced as the winner of the Wellcome Photography Prize, as well as being shortlisted for the 2025 Aesthetica Art Prize. She’s also previous received Genesis Imaging Award for FORMAT Festival 2025 and a Sony World Photography Award. We spoke to the artist about the making of the images, the role of photography in giving marginalised communities a voice and how her images are breaking down cultural stigma.

A: How did you start working behind the lens?

SS: Mine is the story of a trailing partner, an immigrant, a survivor of child abuse – someone carrying the weight of trauma and the colonial hangover of being a brown woman navigating identity in a new country. I moved to the UK in 2009 after getting married. The emotional residue of my past, compounded by cultural isolation and a loss of self, led to a profound sense of disorientation and depression. Then my daughter, Aayat, was born, and in taking pictures of her with an old amateur camera, I found an unexpected way back to myself. Photography became more than documentation; it became a form of therapy and a means of translating an inner landscape for which I had no words. What began as a personal act of healing slowly evolved into a practice of visual activism.

A: Where did the initial idea for the series come from?

SS: Almost everything I’ve made stems from lived experience, whether it’s childhood trauma, intergenerational violence, or witnessing the quiet resilience of those around me. These aren’t abstract “themes” I’ve chosen; they are landscapes I’ve personally walked through. My work begins with questions: What happens to a person when grief is inherited? When silence is taught? When shame becomes cultural memory? A Thousand Cuts was shaped by these inquiries. It grew out of a need to heal from growing up in a home where violence was the norm, but it also sought to hold space for others.

A: A Thousand Cuts is rooted in trust and shared experience with domestic abuse survivors in South Asian communities. How did you navigate the emotional responsibility of this task, and what does collaboration look like in such an intimate context?

SS: The featured women shared things they’d never been allowed to say out loud. They are survivors of domestic abuse, cultural gaslighting, emotional abandonment, sexual violence and the suffocation of financial and social control. I spent months listening. Sometimes I would just sit with them, without pressing for narrative clarity or artistic output. I wasn’t collecting information; I was forming relationships. I entered the room with my own vulnerabilities. The work was built on mutual grief. I wanted the project to move away from western or colonial ideas of authorship or extractive participation, instead taking a more decolonial approach – one grounded in consent, open dialogue, and clear, continuous communication. I didn’t impose the language of “agency” onto them. Instead, we co-created a process that was fluid, honest and entirely non-judgmental. There was a recurring emotion that every survivor described: a feeling of being torn apart from within. These inner ruptures became the visual imprints on the final artworks, represented through the hand-cut patterns that define A Thousand Cuts.

A: You also worked with the charity SHEWISE to produce this series. Why was this partnership important?

SS: SHEWISE was instrumental in connecting me with the survivors. From the outset, I was clear with them: I had no predetermined end goal for this work. I didn’t know if it would ever find an audience or be exhibited. It was important to be honest about that. As a survivor myself, I often struggle to trust my own voice. But I knew that if I was to even attempt breaking the cycle of abuse through art, I had to honour these stories in an ethical manner. That’s why the first intervention was made in partnership with SHEWISE. They arranged for caseworkers to oversee my interactions with the women, recognising that I am not a trained mental health professional, nor an expert in the complex individual challenges each person was navigating. These women are not just emotionally vulnerable, they are in the midst of legal battles, caring for children who have witnessed profound trauma, and rebuilding their lives from the ground up. I lack formal training, but my own experiences have shaped my understanding of how distress imprints on the body and mind. I approached each conversation using trauma-informed care principles: never pressing for details, always allowing space, and being mindful of avoiding discomfort.

A: The images are made by applying the Indian paper-cutting technique Sanjhi to overlay each photograph. Why were you drawn to this method and why do you think it’s so effective at expressing your desired message?

SS: To begin with, I felt that photography alone was not a complete or sufficient medium for this work. I was engaging with nuanced personal histories. They are intensely intimate, yet inextricably linked to broader systems of cultural memory, religious indoctrination, institutional power and political discourse. These forces operate on a macro level, but their impact is most acutely felt in the microcosm of the domestic setting. My challenge, and responsibility, was to hold both: to make visible these larger societal structures while honouring the specificity and dignity of the individual. The quick act of taking a photograph, although important, just wasn’t enough. Instead, working with the printed image over several hours, sometimes days, allowed me to spend extended time in a kind of contemplative proximity to each participant. There was also a more difficult, uncomfortable aspect of the process that I felt the need to explore. As a survivor myself, I have long grappled with the question: what compels a perpetrator? In making these cuts – literally wounding the image – I also began to embody, in a symbolic way, the figure of the abuser. There is a rhythm to violence, a disturbing order in destruction, almost like a form of meditation. In engaging with this repetition through art, I sought to better understand the psychology of harm – not to justify it, but to confront it. Finally, the history of the Sanjhi art form itself adds another layer of relevance. Sanjhi was traditionally created by the female consorts of the Hindu god Krishna to capture his attention; an act steeped in longing, performance and patriarchal imbalance. This backstory echoes the themes within A Thousand Cuts: particularly the silent endurance and aestheticisation of female suffering.

A: You also draw on the metaphor of “Lingchi”, an ancient torture method, to reflect the soul-eroding nature of repeated harm. Could you tell us more about how this concept influenced the project?

SS: The true influence behind A Thousand Cuts was the emotional texture of the survivors’ histories. In every single conversation, I heard variations of the same sentiment: “I feel torn apart from within… in a way that I know I am falling apart, yet somehow… just somehow, I am still holding it together.” That haunting resilience amidst fragmentation became the emotional spine of the project. I wanted to represent this through metaphor rather than literal depiction because any attempt to illustrate trauma in overt, explicit terms risks oversimplifying its complexity. The metaphor of Lingchi, or “death by a thousand cuts,” became a poignant way to capture the cyclical nature of abuse: a slow, repetitive wearing down of the soul, identity and body. In the original act of Lingchi, the predator made small, deliberate incisions, not to kill the person immediately, but to prolong the pain. Over time, the victim would stop feeling it altogether. This, to me, echoes what repeated abuse can do, not just in how it’s normalised by the abuser, but more tragically, in how it becomes internalised by the abused. It allowed us to gesture toward that embedded violence – quiet, cumulative, and soul-eroding – without diminishing the complexity of each woman’s story.

A: How did the women involved respond to the series?

SS: I’ve remained in regular touch with the participants. We often comment on each other’s social media posts and stay connected through WhatsApp. This is not a one-time collaboration, it’s a long-term relationship grounded in trust and mutual respect. Each person was intrinsically involved in the making of her portrait. I would discuss potential visual patterns with them and ask how they wanted to be seen. The work belongs as much to them as it does to me. Naturally, they’ve all seen the final series. In fact, just today I messaged the survivors whose pictures are currently on display at the Francis Crick Institute, and several of them replied saying they’ll make sure to visit the exhibition. One of them shared with me that she’s now working on her LLM legal dissertation and is about to start interning at a law firm. My heart is full of pride for her. This is the same woman who was locked inside a house for five months, only allowed out to work in her perpetrator’s restaurant. To witness her transformation has been deeply humbling.

A: You’ve said this project “offers a means of reclaiming narrative.” How did you define the line between anonymity and visibility when telling these stories?

SS: In South Asian culture, concepts like haya (modesty), sharam (shame), parda (veil) and ghunghat (head covering) are more than traditions, they are embedded totems that have shaped the lives of women for generations. We are culturally trained to exist within the realm of invisibility, where silence is seen as dignity and erasure becomes a form of preservation. We, the survivors in this work, come from a collective history where our only place was along the margins. So for this project, the idea was never to force visibility in the conventional sense, but rather to allow the women to reclaim how they wish to be viewed on their own terms. To be seen while remaining invisible is not an act of dishonouring their narratives. It’s a way of asserting agency within a cultural framework that often denies it. It’s a way of saying: “you cannot erase me, even if you don’t see all of me.” That, in itself, is a radical form of strength.

A: What role do you believe photography can play in dismantling cultural stigma around domestic violence and mental health?

SS: Photography, and art more broadly, can be powerful catalysts for structural change, but only when they operate in partnership with other disciplines and with those who carry lived experience. On their own, images can provoke empathy, raise awareness or open dialogue, but without grounding in community, context, and care, they risk becoming extractive or performative. When art is made in isolation, without accountability to those it seeks to represent, it can result in a partial truth. Sometimes, a half-truth is more damaging than silence. For me, the goal has never been to “speak for” survivors, but to speak as one. That’s where photography becomes more than image-making, it is an act of social witnessing.

A: As well as winning the Wellcome Photography Prize, you’ve also recently been awarded the Realisation Grant from the Centre for British Photography and you are part of the shortlist for the 2025 Aesthetica Art Prize. How does it feel to have your work recognised in this way?

SS: These platforms are incredibly important because they amplify voices that have long been silenced. The fact that lived experiences of violence are being recognised as “art” is a historic shift. I can never diminish the significance of these recognitions – they not only validate the work emotionally, but they also enable it practically. The Realisation Grant from the Centre for British Photography will allow me to bring the histories of 15 more domestic abuse survivors into both the public and artistic domains. That’s a huge support. As for the Wellcome Prize, I honestly struggle to summarise what it has meant. I’ve been applying to various grants to pursue a project on child sexual abuse, and while recognition has come, funding has remained elusive. The monetary reward from Wellcome will help me get one step closer to beginning the research phase of that critical work. Looking ahead, I hope to translate A Thousand Cuts into a book. That will require substantial funding and guidance, and if the Aesthetica Art Prize recognition leads to a win, it would be a huge step forward in furthering my mission to speak from the margins through art.

A: What do you hope audiences take away from viewing the series?

SS: I hope viewers engage with the photographs with openness and empathy. My intention was to create works that are visually striking, so they draw people in, not push them away. I wanted to design a space that fosters conversation rather than confrontation. If the work can hold a viewer’s attention long enough to shift perception, spark dialogue or even just allow someone to sit with discomfort without turning away, then it has done its job. At its core, A Thousand Cuts is an invitation to listen.

A Thousand Cuts is the winner of the 2025 Wellcome Photography Prize: wellcome.org

Words: Emma Jacob & Sujata Setia

Image Credits:

1&6. Sujata Setia, “कितनी गिरह?” (How many more Knots?), from A Thousand Cuts (2023). Image courtesy of the artist.

2. Sujata Setia, “मिट्टी के दायरे” (Circles in Sand), from A Thousand Cuts (2023). Image courtesy of the artist.

3. Sujata Setia, “सपनों कि साज़िश” (Conspiracy of Dreams), from A Thousand Cuts (2023). Image courtesy of the artist.

4. Sujata Setia, “मुझसे मुलाकात” (Finding Me), from A Thousand Cuts (2023). Image courtesy of the artist.

5. Sujata Setia, “मेरी हद्द” (The premise of my existence), from A Thousand Cuts (2023). Image courtesy of the artist.