Examining the use of photography to question the nature of accepted

truths and subjective realities, the images sit between fact and fiction.

Max Pinckers’ Margins of Excess – a photographic series most recently exhibited as part of Belfast Photo Festival’s 2019 edition themed Truth and Lies – focuses on the stories of six characters based in North America. All of them received nationwide attention in the press because of their attempts to realise a dream, but were presented as frauds by mass media. These included Rachel Dolezal, a civil-rights activist who was born white but believes herself to be African American – and Richard Heene, who reported that his six-year-old son had been carried into the skies of eastern Colorado in a 20 foot-wide, flying saucer-shaped helium balloon.

A: Your work speaks to the post-truth era. In fact, you were travelling in the USA when the dialogues about fake news reached a climax. How did this affect you?

MP: When I began Margins of Excess in July 2016 – together with my wife Victoria Gonzalez-Figueras – the term “fake news” wasn’t around yet, and the idea of post-truth wasn’t as common as it is today. Although the series wasn’t conceived as a project about alternative facts, during the production, I did look at some of the alternative news locations but I chose not to keep these threads in the work as I felt it would undermine the emotional power of the protagonist’s personal stories, which express extreme idiosyncratic versions of reality. The intention was not to make a documentary that was accusatory of either the mainstream USA media or the people that I interviewed, but rather to point out that personal truths are sometimes in conflict with general shared ideas, and that when attempting to tell these stories in the form of images, we may come closer to a representation in which both are plausible. In relation to fake news, it does seem that true power lies in the transformation of politics into a strange theatre where nobody knows what is accurate or false, keeping any opposition constantly confused. This has ushered in an age of hyper-individualism, where people’s personal and subjective beliefs are more important to them than facts that may refute them. Yet, it’s important not to forget that truth of course does exist. We just seem disconnected and confused about the form in which we receive this information.

A: Can you describe the different types of imagery in the book and the strategies used to differentiate them as part of a larger, interconnected series?

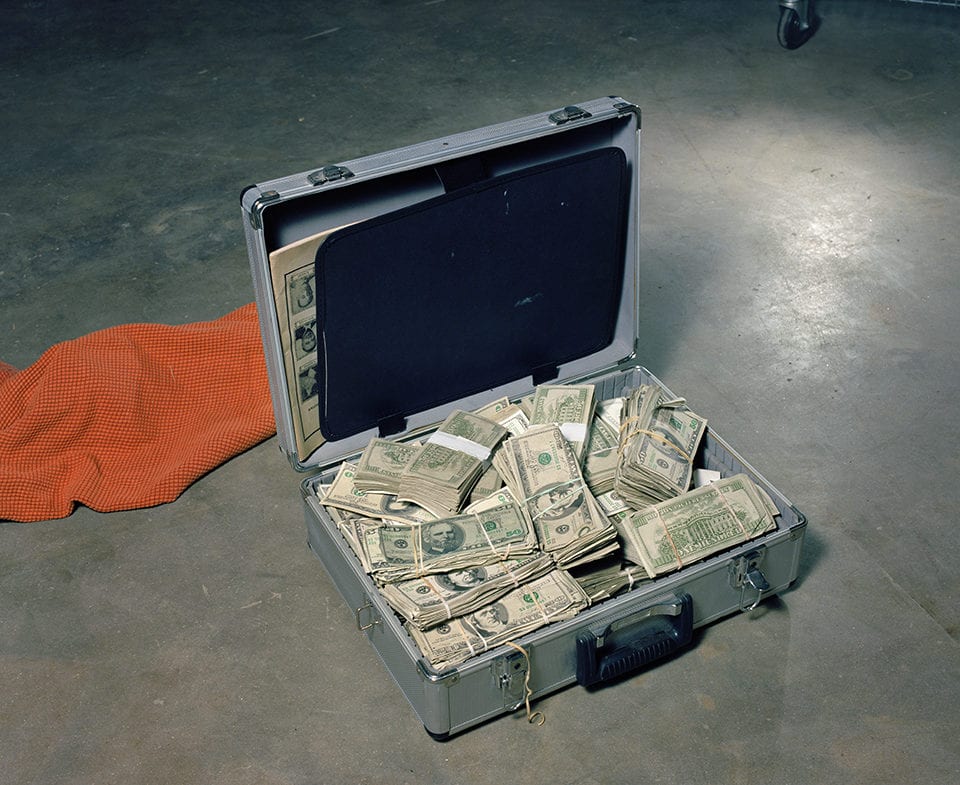

MP: The protagonists are represented in the form of a portrait, sometimes accompanied by shots of their personal living spaces or details of interiors, archival photographs or news footage. They are embedded in various registers of text: a headline and an entire press article from a newspaper source (on grey paper), a first-person quote overlaid onto an image, and a four-page interview in the form of a monologue. Entwined within this structure are image sequences that do not directly relate to the life of the protagonists in a documentary sense, but rather contribute to the narrative as imaginary associations. Because the stories deal with how people attempt to materialise their intimate dreams and desires, they provided the space for me to use my own imagination in visualising these fantastic narratives with symbolic photographs made whilst on the road in-between visits.

A: Can you provide an example of one of the protagonists and how you embedded further layers of meaning?

MP: Herman Rosenblat (1929-2015) was a Jewish-American author known for writing a fictitious Holocaust memoir titled Angel at the Fence (2009). In Rosenblat’s account, his future spouse threw him apples whilst he was held in a German death camp. In relation to this, I photographed an orange being thrown over a fence. I have the freedom to manipulate the representation of these stories since they are rooted in imagination anyway. The choice of this fruit is simply because an orange is more beautiful against the bright blue background of the sky (and also references John Baldessari’s Throwing Three Balls in the Air to Get a Straight Line, 1973). This narrative strategy is key to understanding the intention behind the work, where there doesn’t need to be a binary opposition between what is “real” and what isn’t. Margins of Excess provides a continuous fluctuation between different hierarchies of truths and their relativity towards each other, coming to terms with reality rather than attempting to rationalise and objectify it.

A: Why did you decide to focus on six characters?

MP: In documentary photography especially, the single subject tends to dominate the photographer’s intentions and approach, overshadowing the reflexive nature of the work (especially when dealing with sensational subjects or stories). By combining different layers, the reader is required to reflect on the connections between them, instead of being absorbed in the individual stories. The narratives of six protagonists are not divided into clearly defined chapters, but flow over into each other as if zapping on television or flipping through a magazine, interrupted by sensational mini-news tales that deal with different visual interpretations of authenticity. For example, Jay J. Armes’ section is preceded by a television news report of a Virgin Mary statue at Saint Mary’s Church in Indiana reportedly crying with tears running down the statue’s cheek. The Heene family sequence flows over into an early UFO hoax from 1953 in which a monkey is mistaken for an alien. Ali Alqaisi’s narrative skips from the US military accidentally dropping an atomic bomb on US soil, to the first cloned military dog, “Specter.”

A: Many of the images are self-aware, both as entities that exist between fact and fiction and as wider symbols or tropes. Can you speak a little more about this?

MP: I experienced the USA as one big cliché, an exaggeration of its own stereotype. It is a place of pure superficiality derived of substance (like coffee without caffeine, alcohol-free beer or butter without fat), like a photograph. I began working with young actors in New York City and Hollywood to produce pieces that could be used as empty templates, or a kind of “stock photojournalism” – empty containers of the perfect trope, employable in whichever context for whichever tragic event. Classic examples that the media applies after terrible events are close-ups of people embracing each other, or portraits of spectators crying. These images have a huge emotional impact on the readers as they can easily identify with them, much more so than images of the actual transgressive event. Works like these, made with actors, are woven throughout the book. They seem to weep in our stead like an ancient Greek choir. The cover of the book bears one such image, made on Trump’s inauguration day.

A: Interpretive texts are excluded from the book and installation. It means that the significance of some images remains hidden. Why did you make this decision?

MP: Text is mostly used directly in relation to visuals where it is necessary to move the narrative forward. I like to embrace the multitude of meanings inherent to photographs, which continually change depending on the context and time they appear in, and who looks at them. Many of the sequences in the book have distinct references and reasons for being constructed, although I prefer not to disclose this. Much of the pleasure of delving into a complex body of work lies in the reward of noticing and understanding its meaning. Much of this is in the detail. There are clues and references in the various texts that relate to certain images, but that are harder to find. For example, in an interview, Ali Alqaisi describes that he had his bathtub removed because it gives him anxiety, having been waterboarded 17 times during his time at Abu Ghraib prison. Just 16 pages prior there is an image of a void in Alqaisi’s bathroom where his bathtub used to stand, next to which a second image depicts a Middle Eastern-themed diorama exhibit from an American military museum. It displays a collection of plastic water bottles under a flatscreen that reads “in war, nothing is as it should be.”

A: This approach, and the layers of information, is the exact opposite of today’s mode of instant gratification. How does it produce a different type of critical reader?

MP: I’m interested in how there’s a necessity for documentary to be reflexive about its own constructions. That we as documentarians should try to communicate to our readers that they should not just take for granted the (visual) information that they consume, but critically reflect on what currency this may have in our visual economy. In an age of endless newsfeeds, clickbait, narcissism, bite-sized infotainment, personalised advertising, confusion, and simplistic good versus evil narratives, documentary should embrace the complexity and ambivalence of the reality with which it tries to comprehend. But I also find it important that my work expresses itself in an aesthetic form that is accessible to anyone, and functions on different levels of interpretation, without being too hermetic or self-referential.

A: Since 2010 you’ve had over 100 exhibitions, won over seven awards and published eight books. What’s next?

MP: In 2014, I went to the Archive of Modern Conflict in London, where I encountered a collection of original documents from the British Ministry of Information relating to the Mau Mau emergency crisis in Kenya in the 1950s. Kenyan freedom fighters took arms against the colonial administration. The events leading up to Britain’s exit from Kenya have become part of a carefully curated history. This includes a skewed representation of the Kenyan fight for independence through a well-oiled propaganda machine of imperial rule. (According to the Kenya Human Rights Commission, an estimated 160,000 Kikuyu were placed in concentration camps and 90,000 people were executed, tortured or subjected to violence). For the past four years, as part of a PhD project at the School of Arts / KASK in Ghent, I have been collaborating with Mau Mau veterans who are now over 80 years of age, creating reenactments in which they claim their roles as victims instead of perpetrators. The reconstructions confront the spectres of colonial oppression.

Sarah Allen