In 1917, Georgia O’Keeffe spent a few days in Santa Fe, New Mexico, and was instantly smitten. “There is so much more space between the ground and sky out here it is tremendous. I want to stay,” she wrote to her husband, the photographer Alfred Stieglitz. By 1929 she was back, and soon spending most of her time in the southwestern state. In 1940 she bought a property on Ghost Ranch, a 21,000-acre retreat and education centre located close to the village of Abiquiú in Rio Arriba County. She installed large picture windows, and furnished it in mid-century style, but the house itself was traditional, built from adobe (earth, clay and straw) and in the style of indigenous populations. O’Keeffe was known as the “Mother of American Modernism,” but for her, the ancient and the cutting-edge merged comfortably in New Mexico. As design writer Helen Thompson (Elle Decor, Country Home and Architectural Digest) points out, after moving to the area: “Every painting she did is of the geology, of the mountains outside the window and those plateaux. They’re of the land.”

Thompson is about to publish a title with Monacelli, which explores the connection between New Mexico’s landscape, its ancient buildings and 21st century architecture, working with photographer Casey Dunn. It’s the third book the pair have made together, after two other very successful collabora- tions, Texas Made/Texas Modern: The House and the Land, and Marfa Modern: Artistic Interiors of the West Texas High Desert. Their new publication is titled Santa Fe Modern, and focuses on 20 houses in the town, each quite distinct but equally ar- resting in their combination of the age-old and the cutting- edge. Thompson says she didn’t want to just make a coffee table book and she’s nailed it – Santa Fe Modern would look good in the centre of any room, however, it also provides a much deeper conversation and approach to the natural and built environment. Thompson’s sheer enthusiasm for Santa Fe comes across, and well it might. “I lived in Austin, Texas, for all of my life, but I came up here to work on this publication and just stayed,” she laughs. “I like it here.”

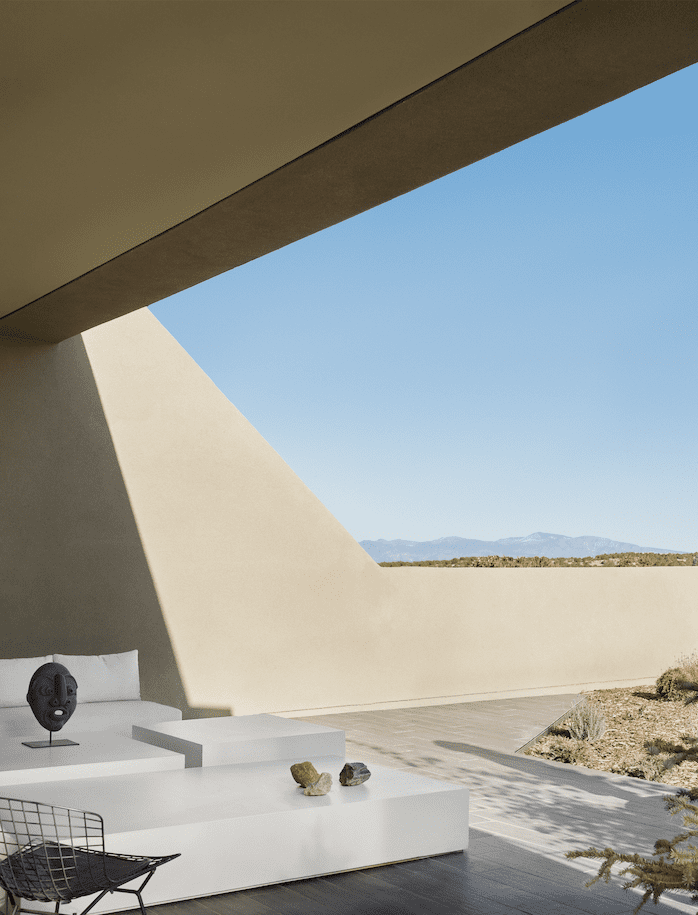

It’s easy to see why. Surrounded by the Jemez and Sangre de Cristo Mountains, Santa Fe sits on a desert plain, which gives it the open skies and sense of space that so struck O’Keeffe. It also gives a clear scope of the land, and the ages- old processes that have made it. It’s easy to think in terms of eons not epochs there, and to therefore collapse the distance between planetary time, indigenous peoples, 20th century Modernism and contemporary inhabitants.

New Mexico has long attracted artists and their patrons – including Mabel Dodge Luhan, who originally invited O’Keeffe the area, or more recent makers such as the minimalist sculptor John McCracken and art dealer Max Protetch. Thompson says the desert landscape draws in free spirits because it’s so far removed from conventional lawns and white-picket fences. The quality of the light in Santa Fe is also a pull, though, because the city sits at 7,000 ft above sea level. Whatever the reason, the city packs a cultural punch well above its size, home to just 85,000 people, dozens of private galleries, and an institution called SITE Santa Fe, which ran the USA’s first international art biennial in 1995.

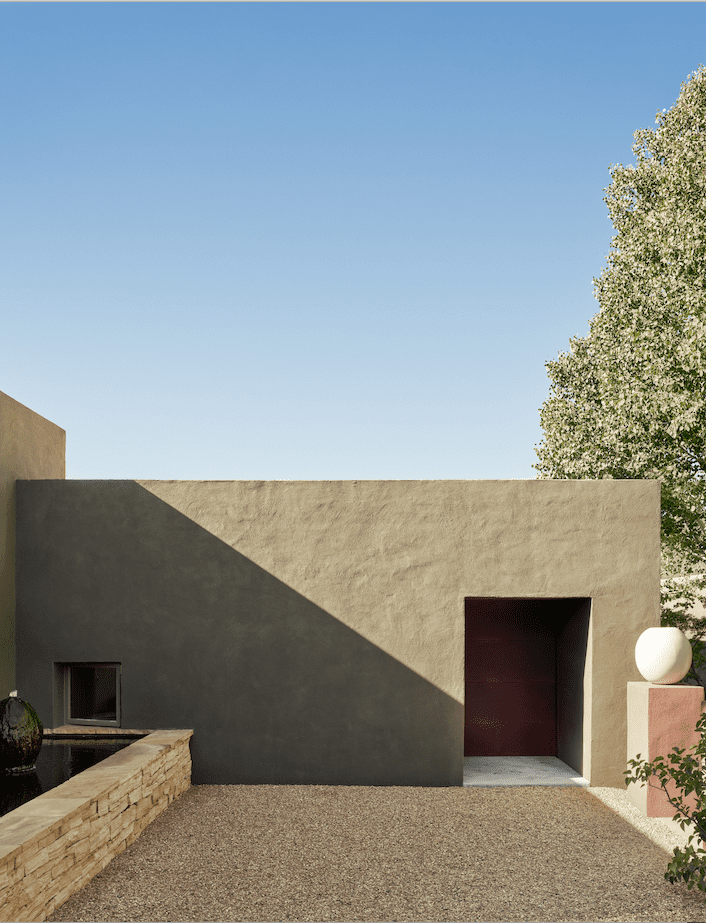

Santa Fe is also the capital of New Mexico and was officially founded in 1609 by Spanish settlers, which makes it the oldest capital in the USA. However, it was inhabited long before that by the local Pueblo or Native American communities, some of which live on today (having survived the arrival of the Europeans). The Tesuque and Nambé Pueblo are not far, and indigenous low-level adobe and cliff- side houses can be seen across the state and beyond. Simple and stark, these homes have a minimal look that echoes 20th century Modernism, and O’Keeffe wasn’t alone in noticing the links. Local architect John Gaw Meem helped spearhead a so-called “Pueblo Revival” across the 1920s and 1930s, for example, combining this architecture with the international Modernist movement to create a pared-down hybrid.

Gaw Meem, who was born in Brazil in 1894 but settled in New Mexico in 1920, also helped to define Santa Fe’s distinctive aesthetic, leading a committee that wrote the 1957 Historical Zoning Ordinance – strict planning laws that determined that “all future buildings in central Santa Fe adhere to the idioms of the Old Quarter” or, if outside that specific area, be of sympathetic materials, colours and proportions. It sounds onerous and sometimes is, as one of the founders of SITE, Laura Carpenter, ruefully attests in the foreword to Santa Fe Modern, in which she writes of a battle to keep her old town building painted yellow [she argued, successfully, the colour predated the laws].

However, as Thompson points out, using age-old methods isn’t just an aesthetic choice. It’s also a sensible, tried-and- tested response to the environment. “It’s rather harsh here,” she says. “You have to figure out ways to incorporate the landscape. That’s what the big windows do [giving stunning views], but they all also have the large porches that make it bearable to be outside when it’s hot. These are longstanding strategies to deal with desert living. Whilst there are houses that look more contemporary, they resort to former methods.” Thompson is passionate about site-specific architecture, “a Modernism that looks like it belongs,” and as she points out, Santa Fe pretty much demands it. The sun is powerful and temperatures can reach up to 38 degrees centigrade in summer, yet it can also snow in winter – as Dunn shows in some wintry shots. It’s extreme, and that means homes here have to offer protection. One property, for example, has been designed to minimise direct sunshine, so that the owner’s photographs and prints are not destroyed by the light. In Modernist architecture, form follows function, and in Santa Fe that’s a conscious decision and then some.

Furthermore, it’s not just the climate that’s uncompromising. Santa Fe’s terrain is rocky and mountainous, and, like the indigenous people, newer residents have often found it’s better to go with the flow than try to fight it. Some homes are built right into a cliff – something people have done for thousands of years; the raw rock left on-show to create a jaw-dropping feature in an already impressive property. In another home, the owner couldn’t extend horizontally, because it would involve chiselling away at a hill, so instead, he built on top – a process familiar with Pueblo homes. “The concept of ‘adding on’ is ancient. People here have always built onto their houses in an organic way,” says Thompson.

Santa Fe has a less precious aesthetic than elsewhere though, a place in which “imperfection is welcome.” Accord- ingly, whilst all the homes are extremely beautiful – and some are unquestionably show-stoppers– they’re not neces- sarily “sleek.” Thompson says she didn’t want the publication to look like “a real estate catalogue” and so there are some quirky abodes, such as “a rambling 1940s house” that had a colourful past as a bar / restaurant and “a free-spirited floor- ing scheme.” Materials are brought together in an improvisational way; rather than ripping it up and starting again, the current owners just added in another texture.

Santa Fe Modern also features some relatively modest properties, such as a 900-square-foot home. Designed to be environmentally conscious, this particular house is also quite literally friendly to nature – the living area has two walls of glass sliding doors and, when they’re opened up, birds come and freely fly through. This ability to blur interior and exterior adds a sense of open expanse and possibility to compact residences, but it’s also second nature in New Mexico: “Even the cliff dwellings had gathering space where you could see the sky.” Santa Fe Modern also includes a home in which a James Turrell Skyspace has been installed (a commission that typically costs up to $2 million) for example, a specifically proportioned chamber with an open aperture in the ceiling. Turrell is an avid pilot and considers the sky his studio; so, naturally, his artwork has found a natural home in Santa Fe, with the infamous Skyspace model based on Turrell’s belief that “everyone has a light in them, and we come together to find that light again and again.”

The geography is, therefore, a huge draw. Reaching far back in time, Thompson explains the historical processes that have shaped the landscape and, though she laughs that she “wrote a lot about geology,” it makes for a compelling read. The view from one porch is “not immediately recognisable for what it is”, then adds that it’s actually “a 40-mile-wide depression, one of three large basins that are part of the Rio Grande rift. This rift – or linear zone whose crust is being slowly torn apart – is a 25 million-year-old scar that emerges at Leadville, Colorado, and comes to a stop in Chihuahua, Mexico. Santa Fe is right in the middle of it.”

This attention to the topography feeds through into an appreciation of raw elements, recalling another key tenet of modernist architecture – “truth to materials.” Many properties in Santa Fe feature Viga ceilings, huge wooden rafters which, along with the latillas (or laths) are usually left exposed to view. In Pueblo homes, these Viga beams can simply be mighty logs, the branches and bark stripped off to the wood. There’s also a residence that uses rammed earth for a feature wall, a technique that’s been employed around the world for millennia, but which is particularly appealing here because of the pink or tan colour of the sedimentary rock.

The décor of these residences pays similar attention to natural raw ecologies – just as O’Keeffe decorated her home with simple rocks and shells. There’s a shady courtyard which uses a piece of solid stone for an outside table, for example, surrounded by elegant (and also dusty pink) Driade chairs. There are also many traditional objects and artefacts which are scattered throughout the landscape and its architecture – Zulu clay pots, for example, or Ashanti stools, vintage Navajo blankets or Acoma ollas. Santa Fe’s most stylish homeowners appreciate fine design whatever its provenance, as did John Gaw Meem, O’Keeffe and other Modernist pioneers.

Although it’s not peculiar to Santa Fe, it’s an approach that may be particularly apt here. Perhaps living in this compelling environment, in which the elements, geology and value of ancient traditions are so clear, gives people a different relationship with time – allowing our instincts to recalibrate, and the five senses to be constantly reinvigorated.

Santa Fe Modern is published by Monacelli. monacellipress.com

Words Diane Smyth

Image Credits:

1. Stucco, glass, and stone residence by Studio Dubois. Santa Fe. Photo by Casey Dunn.

2. House by Ralph Ridgeway. Santa Fe. Photo by Casey Dunn.

3. Stucco house by Van Amburgh+Pares+Co. (constructed around an old adobe house.) Santa Fe. Photo by Casey Dunn.

3. Stucco, glass, and stone residence by Studio Dubois. Santa Fe. Photo by Casey Dunn.

5. Stucco house by Van Amburgh+Pares+Co. (Constructed around an old adobe house.) Santa Fe. Photo by Casey Dunn.

6. Stucco residence and landscape by Seth Anderson. Santa Fe. Photo by Casey Dunn.