To get lost is to release control. It is to resist the compulsion to map, categorise and insist on certainty. In the act of wandering without direction, we open ourselves to chance encounters, to voices and forms that might otherwise go unnoticed. It Requires Getting Lost takes this principle as both its title and its proposition: that by surrendering the desire to know, we might learn anew. The exhibition asks what if uncertainty is not a deficit, but a resource? What if the murky, the tangled, the ungraspable could guide us toward different ways of being in the world? It is a show about humility as much as imagination, about letting go of clarity in order to recognise the strange beauty of entanglement.

The artists gathered here approach this proposition from multiple directions, working across film, photography, painting, sound, projection mapping and sculpture. Their works dwell in thresholds between human and non-human, natural and artificial, intention and accident. The conceptual anchor is borrowed from philosopher and activist Bayo Akomolafe, whose call to “get lost together” becomes both a methodology and an ethos. Darkness, in this sense, is not to be feared but embraced – an ecology of not-knowing, where wonder becomes possible precisely because certainty has been set aside.

The exhibition arises from an unusual collaboration: three artists based in the North of England – Gregory Herbert, Malik Jama and Jocelyn McGregor – spent time immersed in the David and Indrė Roberts Collection, one of the UK’s most significant private collections, alongside visits to sites across the British landscape. From Alderley Edge’s wishing well to Yordas Cave in Ingleton, from Stonehenge to canals and gardens, they encountered spaces where human history and natural process blur. Their research was as much about shared experience as it was about individual practice. Herbert describes the process as vital: “These trips have given us the space to reflect on how our work connects with each other and the collection, whilst also building an ongoing conversation about our entangled relationship with the earth.” This emphasis on art-making as a collaborative wandering, is central to the exhibition’s tone.

Abakanowicz’s monumental textile sculptures anchor these explorations. Her woven forms, simultaneously fragile and resilient, embody collective presence and vulnerability. They resist being read as singular; instead, they appear human, vegetal and architectural all at once. In dialogue with the younger artists, they remind us that to get lost is also to dissolve the boundaries of the individual self, to recognise that identity is porous, interdependent and constantly in flux.

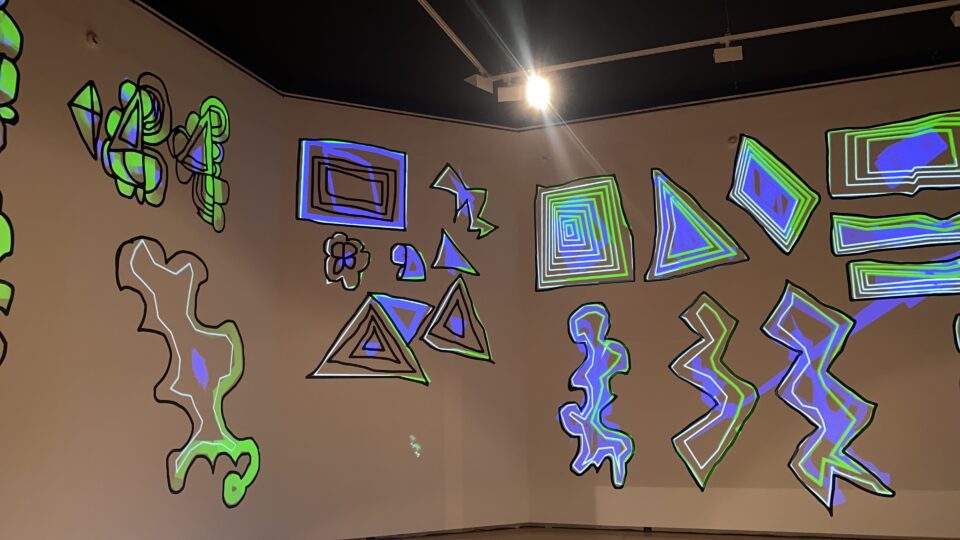

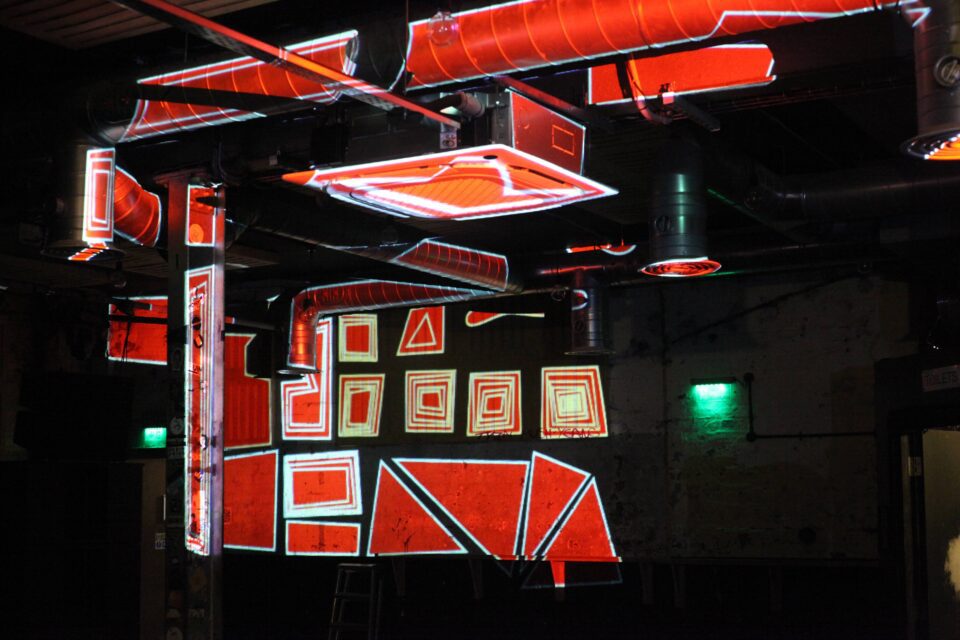

Alongside them, Noémie Goudal stages landscapes that trouble perception. Her work often reveals the constructed nature of what we take to be natural, creating environments that feel at once geological and theatrical. Malik Jama recalls being captivated by her interventions: “I saw art that looked like a cave in a car park by Noémie Goudal and I liked her waterfall too.” This joy in discovery is mirrored in Jama’s own practice of projection mapping and photography, where the everyday is reframed as something wondrous. The echo between Goudal’s illusions and Jama’s digital transformations speaks to the show’s central motif of the cave—both literal and metaphorical – as a site where new understandings emerge.

Pierre Huyghe’s practice similarly inhabits the space between artifice and organism. His worlds within worlds – where living creatures, machines and systems coexist – resist closure. They cannot be fully known, only encountered. To get lost in Huyghe’s work is to acknowledge that we are not the central agents of the world but participants within larger ecologies. His contribution resonates with Herbert’s interest in how organisms interact with their environment, extending the exhibition’s focus on entanglement as a way of thinking and making.

Leon Kossoff might seem, at first, to sit apart from these dialogues. His thickly worked canvases of London streets and figures do not speak of caves or ecosystems. Yet his painterly immersion offers another form of getting lost—an absorption in gesture and process, in the density of urban life as lived matter. Kossoff’s presence suggests that entanglement is not limited to landscapes or non-human environments, but is equally present in the vitality of human cities, where bodies, buildings and histories mesh together.

Wolfgang Tillmans adds yet another register, sharpening our awareness of perception itself. His photographs hold light and atmosphere in suspension, making us conscious of the fragility of seeing. In his images, the cosmic and the intimate overlap; a fragment of paper, a flare of light, a portrait of a friend all speak to the interconnectedness of things. Tillmans’ work, recently celebrated in a major retrospective at MoMA, resonates here with McGregor’s bodily sculptures and Herbert’s ecological experiments, each attentive to the delicate weave of presence and absence.

At the centre of the exhibition are the new works by Herbert, Jama and McGregor. Herbert’s investigations move between sound, sculpture and ecology, attuning us to the feedback loops that sustain life. Jama’s photographs and projections carry the immediacy of his delight in discovery – “I’ve liked taking pictures, walking around seeing things … I’m happy it happened,” he says, his words underscoring a practice that celebrates attention itself. McGregor, meanwhile, brings her hybrid sculptures into dialogue with both her peers and the collection, extending her interest in bodily and organic forms into something more subterranean, part cave, part creature, part landscape. “It’s like having a conversation through art-making,” she reflects, capturing the spirit of the whole project.

The exhibition is conceived as a cavernous, underground space, one where visitors are invited to leave behind certainty and descend into darkness. This staging is not a gimmick but an allegory: in the shadows of not-knowing, other forms of knowledge might surface. The works do not offer solutions or definitive answers; instead, they propose orientations, sensitivities and fragile hopes. By refusing the polished clarity of mastery, they suggest that it is precisely in uncertainty that possibility lies.

In a time defined by the drive for data, clarity and control, the exhibition makes a daring argument: that perhaps we need to get lost. To be at ease with the unknown is not to abandon responsibility, but to cultivate humility, to learn to live more responsively in a world that is continually shifting. The artists gathered here do not instruct us on how to act; rather, they invite us to wander, listen and embrace the subterranean, as a space of transformation. In darkness, there is not absence but another kind of vision, one that might allow us to respond more tenderly, more imaginatively, to the challenges of our time.

It Requires Getting Lost is at Castlefield Gallery, Manchester from 1 November – 22 February 2026: castlefieldgallery.co.uk

Words: Shirley Stevenson

Image Credits:

1&4. Gregory Herbert in collaboration with Professor Katie J. Field, Making-with, 2021. Film still.

2. Gregory Herbert, Sensory Room, 2022. Bluecoat, Liverpool. Photo: Harry Meadley.

3. Malik Jama, Scratch Night at The Lowry, 2023. Projection mapping.

5. Malik Jama, Something On The Wall, 2022. Projection mapping.

6. Noémie Goudal, Warren, 2012. Lambda print, 111 x 137 cm (43 34 x 54 in). Edition of 7 + 2AP. © Noémie Goudal. Courtesy the artist and Edel Assanti.