The world’s first plastic, Bakelite, was invented in 1907 by Leo Baekeland. The material was designed to be both light and durable, formed from a condensation reaction of phenol with formaldehyde. Since then, the substance has become ingrained within societies across the globe, with nearly half of the world’s plastic having been made since 2000. Scientists now predict that the ratio of plastic to fish will be at 1:3 by the year 2025, with the scales tipping the other way soon after.

Mandy Barker (b. 1964) is a prolific British photographer whose work has been published in over 50 countries with the likes of Time, The New Scientist, The Guardian, UNESCO and the World Wildlife Fund, amongst others. Her images, which communicate the severity of the waste age in startling and haunting specificity, have been praised by numerous figures, including the imitable David Attenborough. Her work is now on show at David Brower Center, Berkeley, California, as part of the National Geographic exhibition, Planet or Plastic?

A: When did you start working with plastics? Was there a certain moment that opened your eyes to the issue?

MB: I was a graphic designer, so I’ve always been involved with visual communication, but it was my own experience of finding plastic washed up on my local beach about 15 years ago that really disturbed me. I grew up in Hull, a port on the east coast of the England. Growing up there, I spent a lot of time walking the beaches and collecting natural objects such as stones and driftwood. Over time, I began to notice more and more manmade waste washing up on this particu- lar shoreline, which is also a nature reserve that deer, seals and rare birds inhabit. At this same time, I was studying for a Master’s Degree in photography and I realised that I could use images to inform and educate others about the issue. I presented this idea to the class of 30 students asking if they had heard of marine plastic pollution, and at this time only three people had. I decided then and there that this was an issue people needed to know about, perhaps people who didn’t live near to the sea and couldn’t see what was going on.

A: You’ve been photographing plastics for over 12 years – how has the landscape evolved in the last decade, and, in turn, how have your responses changed since then?

MB: In terms of research, more problems concerning plastic pollution have been identified since I first began; plankton are now eating microplastic particles in the marine environ- ment. The world’s addiction to fast fashion and plastic cloth- ing is a massive problem for many reasons. Particles from car tyre wear is causing toxic runoff. Now, the most detrimental plastic floating through our seas is not simply the floating bottle or food container, but what these objects become when they ultimately break down: microplastic particles are infiltrating organisms at the base of the food chain, and the toxins that they carry affect us all when they’re released.

A: Before moving onto some of your more widely recognised images of “shoals” or “soups”, you primarily worked with images of singular discarded items – PVC gloves, fishing lines, carrier bags and cartons – labelled with the number of years it would take for the item to de-compose, anywhere between one year and an indefinite amount of time for polystyrene. How did these works serve as a test-bed for some of your newer pieces?

MB: INDEFINITE was my first project. It came about from research on different types of plastic and the lengths of time they take to degrade. It horrified me that a fishing line could take 600 years to dissipate in the ocean. I created this series to make people think about the products they con- sume on a daily basis, and ultimately to try and lead them to choose alternatives. Since this series was created in 2010, research by polymer scientists states that all of the conven- tional plastic ever produced, unless burnt, is still with us.

A: Where do you start your research, and how do you select which sites to visit? Can you talk us through the creative process that gets you from point A to B?

MB: My work usually begins with research that I have read about online from ScienceDirect, Marine Pollution Bulletin, and the OceanPlastic List. If there is something I’ve read that I didn’t know about previously, or that I find particularly appalling, then it’s probably fair to say that other people don’t know about it either. This is how I began: with no one having heard about the problem. I have been invited by organisations including Greenpeace and the UK Foreign and Commonwealth Office to join expeditions around the world, accompanying scientists to document what’s been recovered from some of the most remote locations.

A: How do you shoot each selection of plastic?

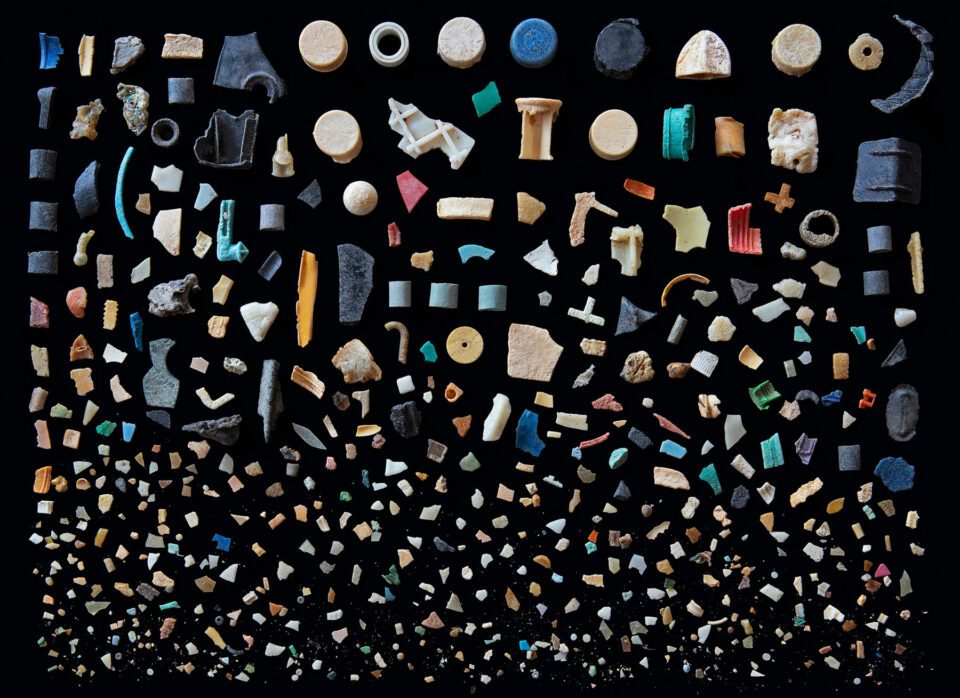

MB: Initially, I experimented with a large format camera and film, hanging plastic from recovered fishing lines and floating on water, but it just wasn’t possible to achieve the depth or scale necessary to duplicate the random way that vast amounts of debris come together in the sea, or to clearly identify each item. To achieve this, I now take varying sizes of plastic, scattering them on a black background. This, combined with a slow shutter speed and a single directional light source, creates the overall feeling of suspension.

A: Your series often include exact numbers, from the particles found within the bodies of animals, to the latitude and longitudes of where debris has been recovered. Today, in the climate crisis, it’s hard to conceive of the vast damage being placed on the planet. The degrees of warming are near indiscernible. How important is it that we remind viewers of explicit numbers and locations, when, for many of us in the global north, the effects are being seen, for the most part, elsewhere?

MB: My images have to be accurate to be believed. It is essential to the integrity of my work that I don’t distort in- formation for the sake of making an interesting image, and that I return the trust shown to me by the scientists who have supported my practice. It is essential that I pass on accurate data and research to the viewer, the public, NGOs, the government etc, otherwise there would be no point in doing it. Science is not subjective; it has no room for aesthetics or emotion, so in that sense, the work of an artist and a scientist are opposed, but we are, in this capacity, seeking the same outcome. It is critical for me to pass on this message: that the global north has primarily created this problem, with the effects mainly being seen in developing countries, most of whom do not have a waste infrastructure.

A: In your journeys across the world, is there a certain kind of plastic, or brand, that recurs time and again?

MB: I recover more or less the same type of plastics all over the world; they’re just adorned with different logos. It is difficult to know where an item has entered the ocean or its journey, but in 2019, I took part in an expedition to Henderson Island, which is an uninhabited location in the middle of the South Pacific Ocean. I had seen photographs of the island before I arrived, but nothing prepared me for its effect. Turtles had weaved their way around tons of debris in order to get out to sea; birds were removing plastic from their nests on a daily basis; at the back of the beach, endemic flora was covered by littered bottles and single- use items. It was truly shocking to identify plastic from over 25 different countries, with 45 major brands and logos rising to the surface again and again. All of it had travelled more than 5,000 kilometres to reach these shorelines.

A: A stark, black background is a recurring aspect, not only providing contrast against the debris, but mimicking the depths of the ocean. Within the frames, the objects are akin to shoals of fish or jellies. What function is there in using photography as an act of imitation?

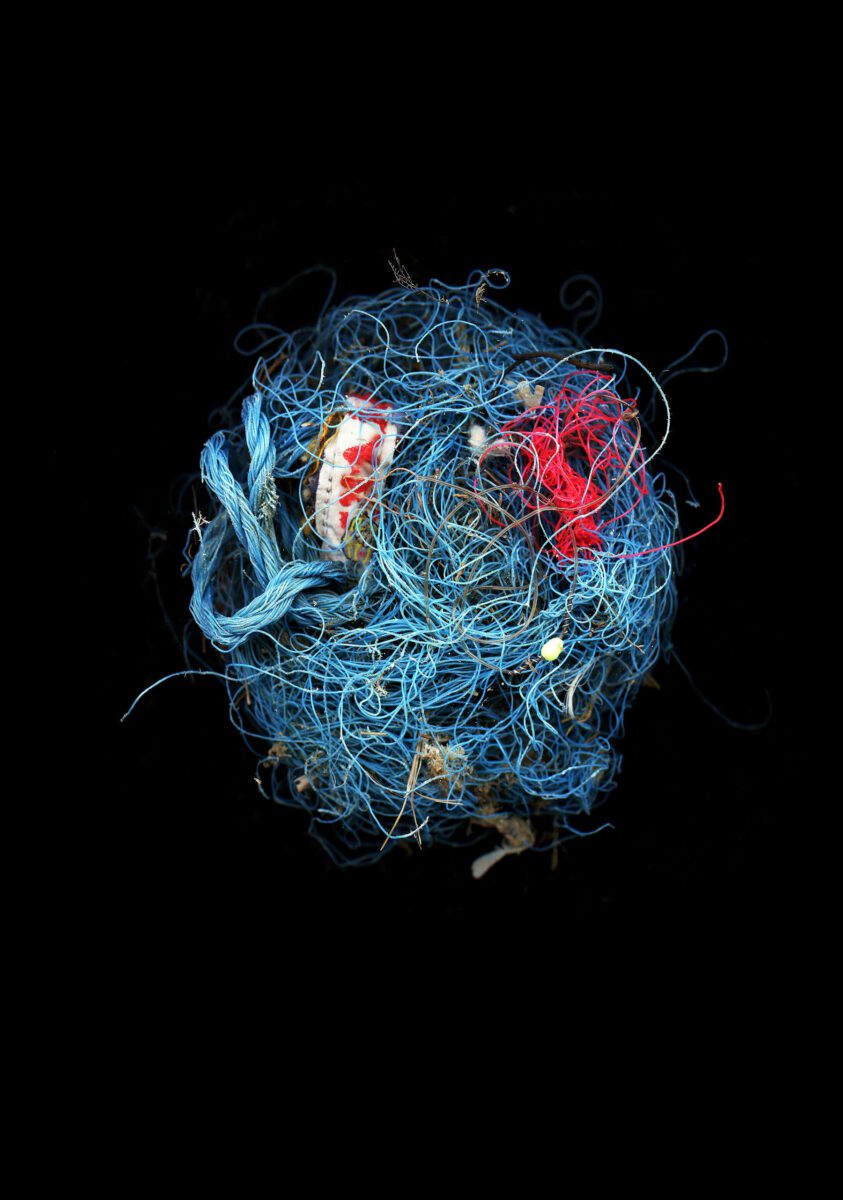

MB: I mimic shoals of jellyfish or plankton to make people initially think that they are looking at a natural creature, perhaps floating in the water column, or under a microscope. It is on closer inspection, the “arrest of interpretation” that then pulls the viewer in and holds their attention for longer. In combination with the caption describing the content, audiences are given the shock or “stab in the back” which will hopefully stir something in their conscience.

A: Whilst your works draw attention to the sheer mass of waste pervading the oceans, they are, still, mesmerising. How do you think this kind of “aesthetic attraction” serves to share the damaging ecological message?

MB: If art has the power to encourage people to act, to move them emotionally, or at the very least make them take notice, then this must be vital to stimulating debate, and, ultimately, change. If I didn’t believe my work did any of these things then I wouldn’t be motivated to continue.

A: In SOUP: 500+, the opening image, the presentation is meticulous, offering a kind of circle, or indeed a cycle of destruction laid out in full. In what way are you calling upon visual semantics, or subliminal information, to express the severity of the waste age?

MB: This piece is a representation of more than 500 pieces of plastic that were found in the stomach of an Albatross chick. People see different things in this image – an iris, a stained-glass window, for example – but really, I created it as a “full stop”, to end the first SOUP series and to the issue itself. I hope this piece will become stored in viewers’ memories, for them to recall through cognitive processes. I hope it will influence their wider conceptual reasoning.

A: What do you have planned for 2022 and beyond?

MB: I have some major solo exhibitions planned in 2022, and I will be artist in residence at The Society of the Four Arts, Palm Beach, Florida in 2023. I am currently working on a long-term project and new approach which I hope will lead to action and international legislation concerning the over consumption and overall manufacture of plastic.

Words: Kate Simpson

Planet or Plastic? David Brower Center, Berkeley, until 4 March. browercenter.org

Image Credits:

1. Mandy Barker, SOUP: 500+ (2011). Representing more than 500 pieces of plastic debris found in the digestive tract of a dead Albatross chick in the North Pacific Gyre.

2. Mandy Barker, INDEFINITE – 600 Years . Monofilament & Macro filament Fishing. Line (2016).

3. Mandy Barker, EVERY… Snowflake Is Different (2011, detail) White marine plastic collected in two single visits to the shoreline at Spurn Point Nature Reserve, England. Courtesty of the artist.

4. Mandy Barker, 276 INSIDE-OUT (2012). 276 Pieces of plastic recovered from the stomach of ONE 90-day old Albatross chick from the Island of Midway, Courtesy of the artist.

5. Mandy Barker, Lost At Sea (2016). Marine plastic debris was recovered from six different continents and six different oceans to represent the hidden world of plastic under the sea. Commissioned by Ikea.