Rieko Whitfield is a Japanese-American artist whose experimental pop music from her debut EP Regenesis has been making waves in the London art scene. As a current artist in residence at the Tate Modern and a recent graduate of the Royal College of Art, she has been gaining a cult following through live performances at the V&A and the ICA.

Regenesis is part of a larger world-building project that centres on life, death, rebirth and the power of community in embodying alternative futures. It will be available to stream on all platforms in October.

A: In Issue 113 of Aesthetica, we feature images from Regenesis. What is it about your pop music that makes it experimental?

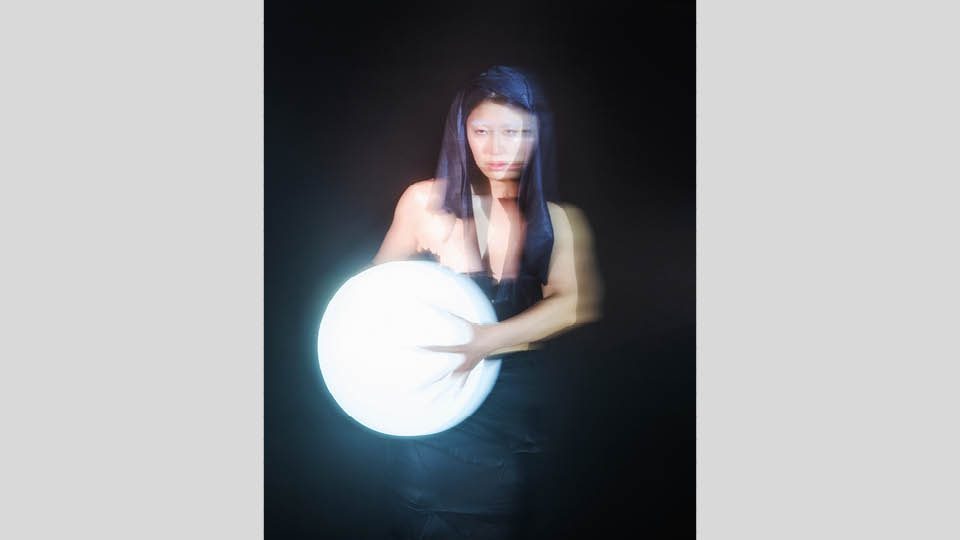

RW: Regenesis is my debut EP dropping 14 October. I categorise my work as “experimental pop” as a musical genre, but I would say it’s my entire approach to music that is experimental. My live shows exist between music and performance art, and the four tracks on Regenesis weave whispered incantations with sounds of water, acapella harmonies with distorted guitar, dissipating screams with echoes of techno beats. Regenesis is a sonic spell for spiritual expansion and collective healing.

A: How much does performance art influence the creation of Regenesis? Or is it that you start with an idea, and then the music and performance germinate from the original idea?

RW: The path to my professional music career is unconventional, almost accidental, because after a long hiatus I started songwriting again for my performance art. I filmed myself performing the songs that would eventually make up the Regenesis EP in front of a green screen in my living room during the COVID-19 pandemic, and those videos started gaining traction as soon as I put them online.

The whole project started from a vision of a supernatural entity during a meditation, and I created a sonic and visual backstory to channel this being to heal a post-apocalyptic Earth. I think my ability to channel is my greatest gift, whether it be through my voice, my body, or my presence, and this translates well to what I do on screen or on stage as a musician.

This being said, music has always been a core part of who I am. I started classical violin training at four and continued with piano lessons on and off, but I really fell in love with songwriting when I picked up my first guitar at age 12. I was organising gigs in my hometown in Southern California, sometimes playing in bands, and spent pretty much every weekend going to shows to support my friends. Being on the stage is really part of my DNA.

Specifically in regard to performance art, I see it as live witchcraft. A true performance artist can alter the entire energy of a room with just their presence. We turn stages into portals.

A: Your recent performances at V&A and the ICA have gained you a cult following in London. How important is this for you?

RW: My community is everything to me. As someone who has moved around my whole life, and an immigrant many times over, I know how special it is to have found my people in London. There’s an edge to this city, and a kind of experimental energy in the art and music scenes here that I feel blessed to come up in.

I’ve also noticed my music tends to attract a certain kind of audience, especially queer people and people of colour, and this is something I cherish. I think the desires for healing and liberation that my music speaks to are universal, but it holds a different weight for people from any marginalised background. There is also a kind of punk, subversive energy in my work that comes from both my personality and my involvement in various subcultures, from my early days in metal music or the queer clubs I tend to frequent now, that comes across in my work.

A: Do you think there is a certain point at which you would like to continue to maintain a cult status, or would you like to bring your music to a wider world and see what happens (whether it be positive or negative)?

RW: Part of my reason for embracing the vernacular of “pop” is because I wanted to reach wider audiences outside of the insular art world. I’m appreciative of the recognition by prestigious art institutions so early in my career, but at the same time I never intended to make work exclusively for people who already have the privilege of access to these spaces.

Even though I was fortunate enough to be trained as a painter, I didn’t really grow up with art I would consider relevant to contemporary culture. I remember being blown away by an Olafur Eliasson work at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art when I went to tour universities as a teenager, and I ended up moving there with dreams of contributing my creative visions to what felt to me like a major metropolis.

I did however grow up constantly listening to music and watching music videos. I didn’t know much about galleries or museums, but I did know about my favourite singers, songwriters, guitarists, and heavy metal bands. There was something so cathartic in the intensity of it – the live shows, the subwoofers, the community of misfits in mosh pits.

Now I think the concept of what contemporary pop music can be is uncharted territory. And what excites me about the art I am drawn to is this crossover between performance art and experimental music at the intersection of galleries, museums, DIY spaces and nightlife. It just feels so much more aligned to real life than the colonial mausoleums of permanent collections, or artefacts inaccessible to most people for acquisition. Music is a pure emotional, vibrational force that belongs to everybody in the present.

I don’t really see popular exposure as positive or negative – all it does is amplify whatever intention or political position you had already held as a human being. There was a time in my life when being seen, being perceived, felt incredibly unsafe. Now I recognise that it is imperative for people like me to work through these shadows and allow ourselves to shine, in societies that teach us to hold shame around being in the spotlight.

Particularly for those who are driven by social change, we can’t be afraid of taking up space. We need artists in the broad sense of the term to gain platforms and provide the voice and the vision for a more compassionate future.

A: Regenesis is part of a larger project that explores concepts and ideas around life, death, rebirth and the power of community in embodying alternative futures. How long have you been working on this larger project?

RW: I started working on Regenesis in its original form – a moving image work of speculative mythology drawing from Japanese creation myths structured as a three-act “opera” – back in 2021 during my postgraduate studies at the Royal College of Art. As you know, this was featured in Issue 104 of Aesthetica as well.

Since then I have professionally re-recorded the music from the opera (co-produced and mixed by Jared Bennett and Ben Gardiner, mastered by Enyang Ha), and have been performing Regenesis live in spaces ranging from museum lates to club nights. So this project has been in a constant state of rebirth and reinvention for the past two years.

A: What are some of the challenges you face in a longer-term project?

RW: I think my brain is wired more like a designer than an artist, constantly prototyping at every stage of a project. The most challenging aspect for me is deciding when a work is in its finished form. Now I am proud to say Regenesis is finally complete.

A: Where do you think Regenesis will go next?

RW: Once I release my EP on streaming platforms, I am ready to let Regenesis go. I’ve already written my next EP, and am beginning to write the first songs of my debut album. Of course there will be shows and tours, and Regenesis will always be an important part of my journey, but I think in hindsight this will mark a time of my life when I was figuring everything out for the first time as I was navigating the art world, the music industry, and my identity as an artist.

A: You are a recent graduate of the Royal College of Art. How has your experience prepared you for a longer-term career in the creative industries?

RW: What I got out of my postgraduate studies is the luxury of time and space to hone my mission. It was a time for me to ask myself questions like: why was I brought into this world to be an artist? What are the messages I am channelling as a vessel for my life’s work? It might sound grandiose, but ultimately I don’t feel like my art is really about me as an individual. When a muse whispers in your ear, this is a gift and a responsibility to the culture that I don’t take lightly.

Being at art school, you also get a crash course on the current discourses in the Western art world. Besides a brief stint at Central Saint Martins on an undergraduate exchange programme, my master’s degree was my first time enrolled in a serious art institution. I had such a sense of imposter syndrome until I realised the freshness, almost naivety of my perspective played to my advantage. Sometimes it’s better to learn the rules before you break them.

I also met so many talented collaborators through the Royal College of Art, and many who I consider my closest friends.

A: As a current artist in residence at Tate Modern, what does a typical day look like for you?

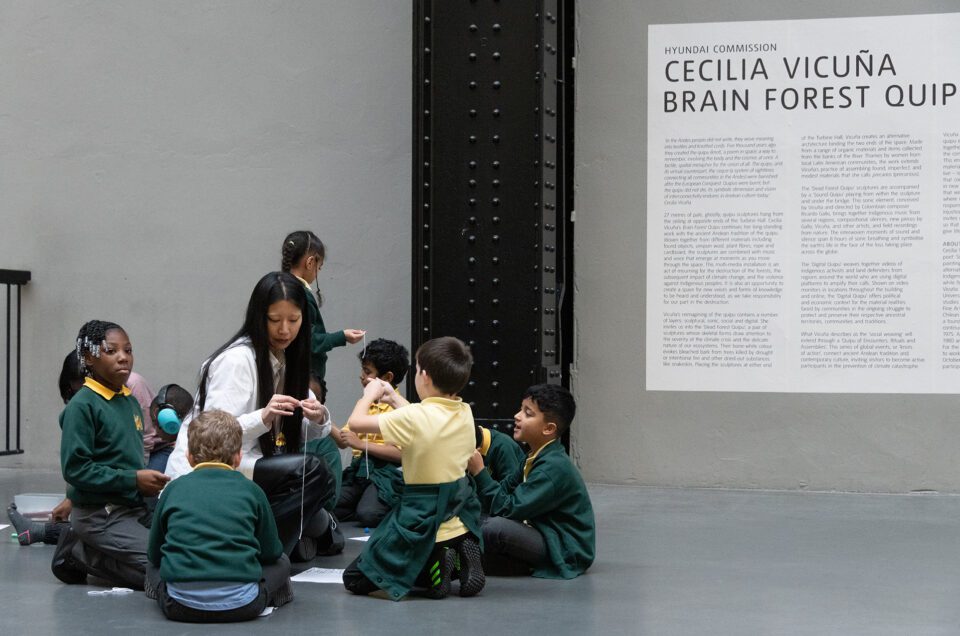

RW: I run workshops relating to works in the Tate Modern collections that resonate with my practice. I primarily worked with Cecilia Vicuña’s 2022 Turbine Hall commission Brain Forest Quipu.

As a schools workshop artist, I engage with younger audiences, often neurodiverse or from underrepresented backgrounds, by hosting guided meditations and automatic writing workshops within Vicuña’s installation.

Quipu is a lost form of communication using knots, indigenous to the Andes of South America, with the entire installation resembling the ghost of a dying forest. In my workshops I had my participants tie knots in a thread to mark tactile timelines of their most formative memories, then through visualisation and writing exercises, channel messages through their past, present and future selves.

Sometimes we would fold up our writing into “Brain Pods” of hope and anticipatory grief, and tie them into our own installation on the rails of the viewing deck overlooking the Vicuña. Other times, I would record the participants reading lines from their writing, and parade around the Tate Modern blasting their voices on a giant speaker. Either way, we undeniably take up space in this institution.

One teacher wrote me feedback that the experience of creating and displaying work alongside the Vicuña helped contribute “to the independence and identity of the group growing up and becoming adults.”

Another teacher broke into tears when they saw the face of one of their non-verbal autistic students light up as they heard their own voice played back through the speaker to the audience in the hall.

In my eyes, if the interactions throughout my residency have made positive impacts on the way even one child views their place in the world, then I know I have done my job well.

A: What advice resonates most with the students?

RW: I close every single one of my workshops on my residency with this message: “Your stories matter just as much as anyone else’s exhibited in the Tate Modern. Thank you for sharing yours in this space.”

A: How do you balance your daily work with your approach to a multidisciplinary practice?

RW: I wish I could say I spend all day in the studio making music, but really a big part of my daily work is production.

And as the scale of my productions have grown larger, my practice has become increasingly more collaborative. One of my favourite elements around music is world-building, and crafting the vibe across cultural industries like film and fashion is really exciting. I loved storyboarding for the music video of my single Ashes to Ashes with director Deividas Vytautas, choreographing in the dance studio with movement director Yen-Ching Lin, moodboarding for shoots with photographer Mika Kailes, and working with stylists like Matt King and Jahnavi Sharma to shape my sartorial aesthetic.

I am also the director of Diasporas Now, a performance art platform championing artists of the global majority, founded in 2021 at the Royal College of Art with Paola Estrella and Lulu Wang who I met on my course. This has been a collective practice in curation and community building, and a way to stay tapped into what is happening in the diasporic performance and music spaces.

But when it comes to writing and to conceptualising, that process is sacred. This to me is a spiritual practice, a daily ritual of love, a conjuring of worlds yet to be envisioned.

My life is my art and my art is my life. What I still definitely need to figure out is how to switch off every once in a while. I suppose every artist learns this in their own way, in their own time.

A: What projects and exhibitions do you have coming up throughout 2023 and 2024?

RW: First and foremost, I am focusing on the release of my music video and single Ashes to Ashes on 29 September, and my Regenesis EP on 14 October. I’ve also got a special track I’m working on with Luca Eck which we will release sometime in November.

On the Diasporas Now front, we are planning a UK-wide tour between Humber Street Gallery in Hull, NN Contemporary Art in Northampton and the Institute of Contemporary Arts in London. I’m really excited to be able to curate and commission so many emerging artists of colour through the funding of the Arts Council England National Lottery Project Grant.

Between the Regenesis release, the Diasporas Now tour and bookings for my own shows across Europe, I am really keen to start production on my next EP.

I think this and next year will be transformative ones for me, so I’m preparing myself physically, mentally, and spiritually in anticipation for what is to come. Ultimately, I’m so grateful to be able to do what I love, alongside creatives whose work I also love.

And perhaps most importantly, I’m just grateful to have reached a point in my personal growth where I can allow myself to shine.

All images courtesy of Rieko Whitfield.

riekowhitfield.com I Instagram: @riekowhitfield

The work of Rieko Whitfield appears in Issue 113 of Aesthetica. Click here to visit our online shop.

Image Credits:

1. Photo by Mika Kailes, styling by Matt King, makeup by Chiharu Wakabayashi, produced by Littledoom Studio, shot at Ghost Studios.

2. Photo by Jesse May Fisher behind the scenes of the Ashes to Ashes music video shoot at Somerset House.

3. Photo by Hydar Dewachi at Friday Lates: Sounding Futures at the Victoria and Albert Museum.

4. Photo by Xavier Andrew at Futur.Shock Chapter 3: Purge at FOLD.

5. Photo by Sonal Bakrania for the Artist-led Schools Workshops at Tate Modern (© Tate, 2022).

6. Photo by Sonal Bakrania for the Artist-led Schools Workshops at Tate Modern (© Tate, 2022).

7. Still from the Ashes to Ashes music video, directed by Deividas Vytautas, shot by Charlie Knight, with special effects by Sybil Montet and fashion design by Olivia Ballard.