For nearly all of photography’s 180-year history, women have shaped the development of the art form. The High Museum of Art in Atlanta delves into its permanent collections to present a survey of women image-makers from the 19th century onwards. Initially intended to open last year on the centenary of the 19th Amendment – marking women’s right to vote – the show will now run until Summer 2021. Sarah Kennel, Curator at the High, describes Underexposed: Women Photographers from the Collection as “an extraordinary opportunity to expand the history of photography and bring greater recognition to the many women who have contributed to and led the field.”

A: Can you tell us a bit more about the story of this show, perhaps especially with reference to the centenary of the 19th amendment?

SK: Indeed, this exhibition was intended to mark the 100th anniversary of the passage of the 19th amendment, but Covid threw a wrench in our scheduling. In a way, that doesn’t really matter, as anniversaries are just reminders to do things we should do anyway. The other impetus was a reflection on the High’s own exhibition history, which has featured many superb monographic exhibitions, but mostly on male photographers (in some ways reflecting the fact that our largest monographic holdings are by male photographers).

A: The exhibition includes work from across the history of the photographic medium, including beautiful 19th-century cyanotypes by Anna Atkins. Can you tell us about the role of women in the early development of the photography?

SK: The few 19th century pieces in the show remind us that women have always been at the forefront of photographic practice. Atkins was the first (known) female photographer in Britain, and also the first person to produce a photo book! Her work combined new ways of imaging the world with a contemporary impulse to categorise and create visual taxonomies, so it lies at the intersection of science, photography and culture. But many other women practiced or contributed to photography in the 19th century.

Some were superstars, like Julia Margaret Cameron, but others have yet to be really researched, like Mary Dillywn. Considered the first female photographer in Wales, she is still far less known than her brother, John Dillwyn-Llewelyn, who was a pioneering photographer in his own right. Finally, we know that women participated in the work of photography from its origins, whether working in factories producing gelatin dry plates or opening their own photographic studios, but so much more research still needs to be done.

A: With reference to the early 20th century work featured in the show, can you expand on how photography reflected ideas of the “New Woman” at this time?

SK: The global emergence of the “New Woman” – as a new icon of female independence – coincided with transformations in photography, and this convergence really led to an explosion of talented women taking up the medium. Along with a general shift toward more women pursuing higher education and professional careers, the shifts in photographic technologies with faster, lighter, cheaper cameras, and the rise of technical schools that offered training in photography, meant that barriers to making and learning about photography were lowered.

Additionally, the rise of the illustrated press in the 1920s and 1930s fuelled both an appetite for pictures but also a recognition that women, as savvy consumers, were equally adept at shaping desire, marketing and creating advertisements, or producing the kind of fresh, innovative fashion spreads or portraits that other women wanted to see. Ilse Bing is a perfect example of the New Woman who is also a new photographer. She first starting making pictures as a teenager with a cheap box camera and then used it as an accessory to her doctoral studies in art history. This encouraged her to pursue photography professionally and she moved to Paris, one of the centres of image production for the press. There she excelled across the board, whether doing street reportage or fashion advertisements or self-portraits.

A: How are the stylistic trends established by the earlier artists featured in the show developed in the more recent and contemporary work on display?

SK: The exhibition deliberately embraces a wide range of photographic styles and processes, in part because it reflects the myriad ways that women photographers have produced work over the past decade. One aspect of the exhibition that fascinates me is the extent to which women, starting in the 1970s, began using the camera in creative and non-traditional ways, whether by going back to the origins of the media to make tintypes or photographs or by combining photography with other media, such as sculpture and collage. This spirit of experimentation characterises much of the work in the show and I think, in many cases, the examples of women successfully forging a career making innovative, non-traditional work encouraged others to follow suit.

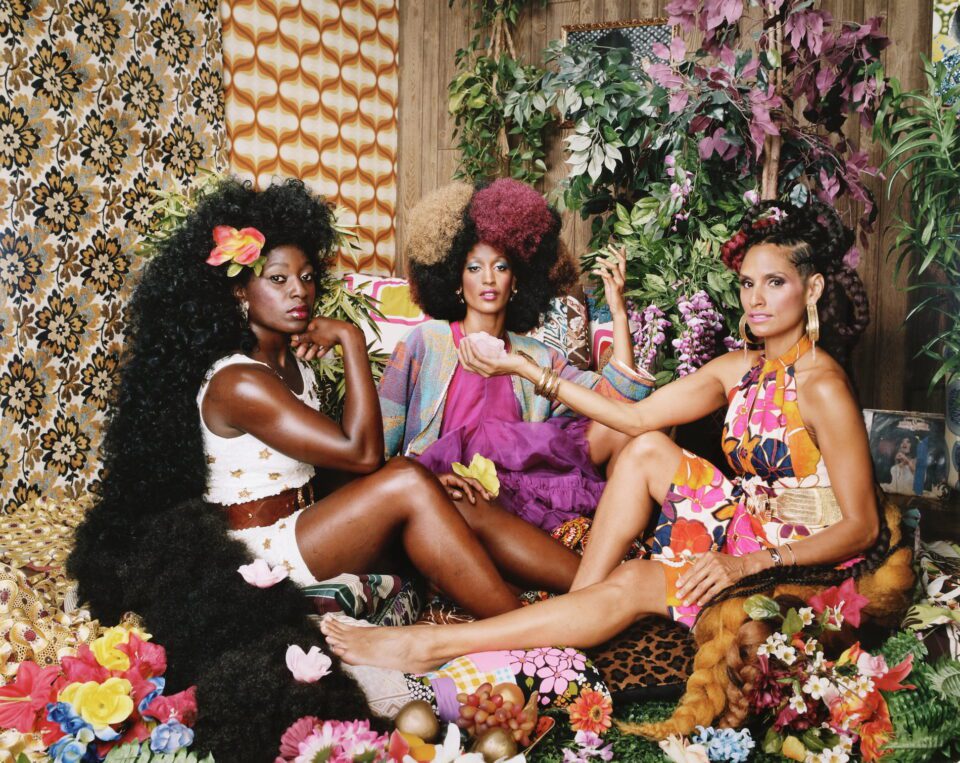

A: Mickalene Thomas’s Trois Femmes Deux offers a restaging of Manet’s Déjeuner sur L’Herbe, inserting black femininity into the scene. How are tropes of black womanhood explored and subverted in this show?

SK: The last part of the exhibition focuses on “strategies of identity,” or how women have used the camera to explore the ways that photography has contributed to mass media depictions of gender, femininity and sexuality. Artists like Mickalene Thomas, Xaviera Simmons, Lorna Simpson, Magdalena Campos-Pons and Carrie Mae Weems explore the intersections of identities.

How have BIPOC women been represented through photography and mass media? How can BIPOC artists use the camera to offer powerful alternative representations of selfhood? Thomas’s Trois Femmes Deux gives agency and thrilling beauty back to women who have so often been the object, rather than the subject, of the gaze, while Xaviera Simmons’s work inserts the artist into a tradition of Western landscape photography, asserting the presence of Black women in a history that has historically excluded or marginalised them.

A: Could you tell us a bit more about how women photographers have interrogated the personal, social and cultural dimensions of gender and identity, as well as ideas of domesticity and femininity?

SK: As my co-curator Maria Kelly and I started combing through our collection, certain themes emerged consistently; themes we did not see as frequently with male artists. These include powerful and sometimes very funny representations of the domestic sphere. For example, Susan Harbage Page’s work examined the uneasy links between white Southern feminine identity and racial terror in the form of the KKK, while Sandy Skoglund’s exploration of the dark side of the suburban dream took the form of a horde of black squirrels running amok on an otherwise picture-perfect patio.

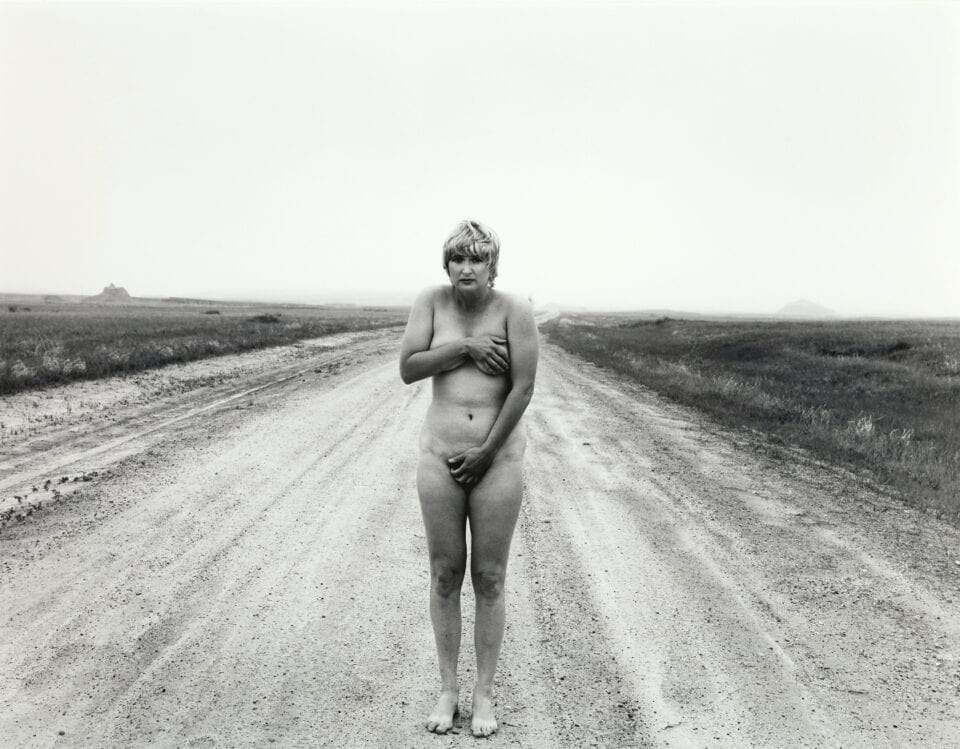

Other photographers have examined the implications of being female and being photographed and looked at, either by using their own bodies as the materials for their art (including Judy Dater and Nancy Floyd) or exploring how women are looked at, generally, with Susan Meiselas’s powerful series on Carnival Strippers. I think what ties many of these works together is an awareness of the power of the gaze along with an awareness of the power of photography to uphold or confront or undermine the gaze and normative notions of identity.

Underexposed runs until 1 August. Find out more here.

Words: Greg Thomas.

Image Credits:

1. Sandy Skoglund (American, born 1946), Gathering Paradise, 1991, dye coupler print, 47 x 60 ½ inches, High Museum of Art, Atlanta, gift of Mr. and Mrs. James L. Henderson, III, 1991.270. © Sandy Skoglund.

2. Mickalene Thomas (American, born 1971), Les Trois Femmes Deux, 2018, dye coupler print, High Museum of Art, Atlanta, purchase with funds from the Friends of Photography, 2018.214. ©Mickalene Thomas / Artist Rights Society (ARS), New York

3. Judy Dater (American, born 1941), Self-Portrait on Deserted Road¸ 1982, gelatin silver print, High Museum of Art, Atlanta, gift of Lucinda W. Bunnen for the Bunnen Collection, 1982.274. © Judy Dater.

4. Nan Goldin (American, born 1953), Cookie and Sharon Dancing in the Back Room, Provincetown, MA, 1976, dye destruction print, High Museum of Art, Atlanta, gift of Lucinda W. Bunnen for the Bunnen Collection, 2005.337.10. © Nan Goldin.