“When I arrived at the High in 2015, the Museum faced a difficult truth: our exceptional collection and world-class architecture could not exclusively make us essential within the diverse and growing city that we call home. That realisation forced us to change. We embraced inclusivity as a value and as a measurable objective.” So writes Rand Suffolk, Director of the High Museum of Art, Atlanta, Georgia, in his introduction to the Museum’s recent report into Art and Inclusion. Put- ting the years 2015-2020 under the microscope, the report outlines the High’s efforts to ensure its collections, programming, audience and staff are fully representative. The fact the document exists is progress, as are initiatives such as a comprehensive rehang of the permanent collection in 2018, which embraced “growth and diversity through storytelling.”

However, as Suffolk also writes: “we’re aware that we’ve not achieved the full measure of change to which we aspire.” The Metro Atlanta area’s population is made up of 49 per cent white individuals and 51 per cent Black, Indigenous citizens or people of colour, yet 80 per cent of the permanent collection on display is by white artists; just nine per cent of that permanent show is by women. It’s against this backdrop that the High’s new exhibition is taking place – the largest of its kind at the institution, with more than 100 pieces from the museum’s holdings, all by women, some never shown before.

Underexposed includes established greats such as Ilse Bing, an innovator and “New Woman” of the 1930s, whose practice was defined by flat planes and strong shadows in the inter-war period, characteristic of Frankfurt’s growing avant- garde scene. Alongside Bing are the likes of Magnum Photos members Susan Meiselas, who shot to fame making pictures of carnival strippers in Pennsylvania, with bare bodies and questions of performance, vulnerability and reclamation rising to the surface. She went on to work in 1970s Nicaragua, with powerful depictions of the revolution and the Somoza regime. Her images of resistance, insurrection, and a climac- tic farewell to autocracy feels relevant once more.

Amongst those setting the groundwork are less familiar (but nonetheless noteworthy) names, such as Sheila Pree Bright, Mickalene Thomas and Jill Frank. And whilst this radical exhibition stands as a well-needed correction, what emerges isn’t the worthy sense of a museum dutifully “fulfilling its quota.” Instead, it’s a vibrant re-imagining of photography, with an intense investigation of identity. Jill Frank notes: “I was struck by the way this show simply reveals a history without a male perspective altogether. Photography, more than other artistic media, was historically relegated to those with access, means and privilege. The art world is characterised by institutional misogyny, but this show avoids a reductive critique. The way it is curated offers an alternative version of the past, taking viewers from the 1800s to our present moment without the canonised conventional perspective of the white male.”

Underexposed was conceived by Sarah Kennel, the Donald and Marilyn Keough Family Curator of Photography, and Maria L. Kelly, Curatorial Assistant of Photography, and both were keen to show that women have been involved with images from their inception – not just rewriting the narrative retrospectively or “filling in the gaps.” Such examples include Anna Atkins, who created groundbreaking botanical cyanotypes way back in 1843. Light and simple chemical processes resulted in impressively detailed blueprints of specimens, from algae to ferns, and pushed the connec- tions between art and science in considered ways.

In its bulk, however, Underexposed is divided into two halves. The first half includes a section which runs from 1920 to the 1950s, and features Margaret Bourke-White, Dorothea Lange and Imogen Cunningham, who broke through when advancements in photography, media and feminism meant they had a fighting chance to do so. This half also includes a section on the technical and conceptual innovations made by women artists from the 1970s to the present-day, and includes practitioners such as Barbara Kasten and Sheila Pinkel alongside innovative contempo- raries such as Meghann Riepenhoff and Elizabeth Turk.

The second half takes a slightly different approach, pinpointing personal, social and cultural dimensions of gender and identity in the last 50 years. There’s a mini section on domesticity and feminine ideals, for example, which emerged as Kelly and Kennel looked through the High’s collection and found that the home recurred as a subject for women photographers – a reflection of the ongoing gender imbalance in domestic work, and on the ideologies surrounding the home’s interiors as a distinctly feminine space. Julie Moos’ 2001 Domestic (Betty and Toni) shows two women side-by-side, one Black and the other white; it’s left to the viewer to consider their relationship. Sheila Pree Bright’s Suburbia series (2008) shows interiors of Black- owned homes around the Atlanta area, giving a platform to the multi-ethnic middle class, and African American suburbia – a landscape traditionally excluded from the media.

There is also a broad section on portraiture and self-por- traiture, subverting the prevailing masculine and hetero- sexual perspective of women’s bodies in the art world. “That section focuses on images of girls and women, made by girls and women, from photojournalism and civil rights to portraiture and conceptual works,” says Kelly. “It does pose the question if there is a ‘female gaze’ present, but we leave that up to the viewer to decide. Rather than dictate who is a suitable model or keep with established norms of women as models, we instead invite you to consider how the con- ditions of making a work, including the gender identity of artist and subject, shape and condition what you see.”

This includes photojournalist Kael Alford, for example, who was in Iraq at the start of the war in 2003, and often depicted women; her access was very different to that of her male counterparts, simply by virtue of her assigned sex. This section also includes Doris Derby’s Grass Roots Organizer, Mississippi (1968), however, an image showing a woman actively involved in the Civil Rights Movement, which has an important history in Atlanta. The subject is politically active in the moment, very far from the archetype of an objectified model presented for (male) titillation. This section also includes a piece by Mickalene Thomas titled Les Trois Femmes Deux (2018) however, which references Édouard Manet’s The Luncheon on the Grass (1863) but replaces the two (clothed) white men and (naked) white women with three glamorously dressed, confidently posing Black women. It’s part of a wider project in which Thomas takes icons of art history and destabilises them, quite literally putting Black femininity and sexuality into the picture.

Jill Frank, meanwhile, launches a very different conversation on photography and power, one that questions re- ceived conventions of both portraiture and societal values. Frank focuses on adolescents – subjects she finds compelling precisely because they haven’t yet found fixed identities. “As we grow older, we learn to close up a bit, but youthful people are more open – more in flux. From childhood to adulthood, through hormonal and physical challenges and mood shifts, there are so many ‘firsts’ and so many surprises in youth. It seems like your body and mind are always in motion and open to change. Photography has the ability to reveal the nuance, beauty and unease of adolescence. Conventional portraits are so fixed, so authoritative – I like the idea of using that formality to document a demographic in a constant state of change.”

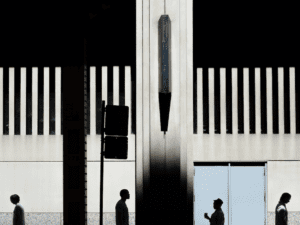

Frank has two portraits in Underexposed, both of the same young woman, and both shot in Athens, under 100 miles from Atlanta. The portraits come from her 2016 series, everyone who woke up at the yellow house, which shows 20 portraits of 10 young people starting their day after a night of drinking and partying, two pictures per individual. The youngsters are tired from their exertions, too tired to strike a pose, yet at the same time their expressions are constant- ly on the move. A young woman picked out by the High is visibly upset in one image, for example, more stoic in the other. Distress, pain, anguish and uncertainty reign.

Frank shows these two images, and the other pairs in the series, as large-scale, double-sided portraits – canonising scenes which might otherwise be considered unimportant, but at the same time, suggesting that traditional, one-shot portraits convey a fake monumentality. In her installations, you have to walk around the whole frame to see the two different takes, and neither one has compositional authority. At the same time, their sheer scale valorises the moments.

Frank makes important assertions on democracy and the ethics of documentation through imagery. “Big fancy por- traits are usually made of established professionals, but I think lives of everyday youth are equally important. I am drawn to under-celebrated moments of social victory and defeat. I purposefully interact with subjects that could be considered superficial or culturally recognisable, banal or clichéd. I think photographs can contradict, loosen, or challenge the preconceived notions about different people, places and activities. I am taking ‘serious’ portraits of a scenes that are, quite often, viewed as trivial.”

It’s a deceptively simple premise with far-reaching implications – Frank’s piece is informed by Pierre Bourdieu’s concept of habitus and 1950s American sociology of deviance, both of which consider social status, who has the power to decide what’s important, and why. These are questions intimately related to Underexposed, and to the ongoing work at both the High and at other pivotal cultural institutions in 2021, as they – in timely fashion – seek to question their conventions and collections anew.

High Museum’s Sarah Kennel continues: “Recent events – the US election of 2016, women’s marches, the rapid growth of the Black Lives Matter movement – have made all institutions recognise that we can’t keep kicking the can down the road and that incremental progress is not enough. But beyond acknowledging that institutions must change, there’s no consensus yet on how to do that exactly. Creating programming that centres voices that have been traditionally marginalised is only one small piece within this.”

Words: Diane Smyth

Underexposed is at High Museum of Art, Atlanta, Until 1 August. | high.org

Image Credits: Jill Frank, everyone who woke up at the yellow house, 2016. Courtesy of the artist.