“Diaspora”, by definition, is a population or community living outside of their traditional or historic home country. For some, this is a voluntary process, moving in pursuit of employment, economic prospects, to be with family or follow educational opportunities. For others, it’s the result of fleeing persecution, danger or natural disasters. It can be a deeply traumatic experience, as was the case with those displaced via the Atlantic slave trade between the 16th and 19th centuries, and leave a legacy through the generations. All of these realities are true for various members of the Black diaspora in the USA. Los Angeles County Museum of Art presents artists working in Africa, Europe and the Americas to expand understandings of the Black diaspora. Exhibiting creatives include some of the biggest names in contemporary art, including Ibrahim Mahama, Igshaan Adams, Lorna Simpson and Yinka Shonibare, as well as emerging talent like Chioma Edinama, Tunji Adeniyi-Jones and Widline Cadet. Artists featured in the exhibition interpret their heritage through the clues and motifs their predecessors left behind. Some reflect on the impact of the slave trade, while others respond to migrant experiences in this century. We spoke to Dhyandra Lawson, Curator of Imagining Black Diaspora, about the process of putting the show together, why this new perspective on the Black experience is so important and what she hopes audiences will take away from visiting the show.

A: Imagining Black Diasporas brings together a diverse range of artists from across the African continent, the Americas, and Europe. How did you approach curating such a wide-ranging, multi-regional exhibition?

DL: I began by assessing LACMA’s contemporary holdings by Black artists from outside the United States. The project grew from there. The museum has limited works by artists from South Africa, for example, so that became a region to focus my research and make acquisitions. I wanted the exhibition to be primarily collection-based so that we would be making investments in artists, rather than just borrowing their work. I wondered if I would find related expressions of experience among different artists. For example, I juxtaposed a video work by Mark Bradford featuring footage of Martha and the Vandellas dancing in the streets, with a film by Sammy Baloji featuring Faustin Linyekula dancing in Lubumbashi copper mines. The works have very different focuses, one examines the distinct history of the 1965 Watts Uprising in Los Angeles and the other mining conditions in the Democratic Republic of Congo. Yet together, they reveal the artists’ shared use of movement to resist oppressive forces. I hope viewers will find these diasporic echoes throughout the exhibition — artistic strategies that express related experiences of being.

A: The exhibition includes both established and emerging artists. How did you approach balancing historical weight with fresh perspectives?

DL: Artists born in the eighties and nineties are reaching a mature point of their practice. I wanted to introduce new voices among works by established artists to find relationships and create friction. As I organised the exhibition artists made comments like, “I was in residency with so and so…” Or “this person was in my grad program…” or “I had drinks with them in Dakar…” and so forth. A community revealed itself – not only a community, but I saw how ideas were being shared internationally. In the 20th century, Pan-African networks of exchange happened through print media; such networks have expanded online, through global residencies, fairs, and other international meetings.

A: How do the artists on display address the ever-increasing globalisation of the modern world?

DL: Black artist-led residencies founded in the last quarter century have fostered new global exchanges. Many artists in the exhibition have diasporic practices. They were born in one place, but their parents are from another. They move to work or study, and they exhibit around the world. Zohra Opoku, for example, was born in Altdöbern in East Germany and now lives in Accra. She has participated in residencies in Dakar, Dubai, and Salvador da Bahia. These global exchanges are shaping art practices and art markets. I found that fragmentation was another aesthetic response to a globalised world. The Black diaspora, encompassing so many cultures and eras, is vast and crowded. Artists use fragmentation as a language to respond to the cacophony of history.

A: You said that: “Often art historians focus on Black artists’ biographies or write evocative accounts of their experiences of oppression, before critically examining their innovations or use of materials…Imagining Black Diasporas highlights Black artists’ aesthetic decisions to amplify their insights.” Could you tell us more about what this means and how it informed your curation?

DL: Following the murder of George Floyd, a wave of art exhibitions in the United States centered Black people’s identity. I observed that many of these projects either highlighted Black joy or experiences of oppression. Such categories troubled me because they limit the complexity of human experience. I craved more scholarship about aesthetics and the way artists use materials. I focused on formal analysis as a way into artists’ biographies and their socio/political situations, rather than the other way around. Historically, Pan-African exhibitions have focused on cultural exchanges in countries adjacent to the Atlantic because of the Middle Passage. Whilst the impact of the transatlantic slave trade is the subject of many works on view, I tried not to make it a dominant theme, preferring to highlight artists’ experiences today.

A: Many of the exhibiting artists engage with political and social issues that are happening around the world today, such Adam Pendleton’s exploration of the “stand-you-ground” laws that exist in 38 US states and gained widespread attention during the Black Lives Matter protests. Where do you see the role of artists and galleries in advocating for social justice?

DL: Artists respond to the world around them and that includes making statements about injustice. Exhibition spaces such as galleries and museums should be safe spaces for people to speak about politics.

A: The show is split into four sections: “speech and silence”, “movement and transformation”, “imagination” and “representation” Tell us more about what these mean and why you chose to divide the experience like this?

DL: The themes derived from finding aesthetic connections among artworks. When I researched the collection I found that language, for example, was a common thread. It may be the only way to communicate the feeling of experience. Then again, words can fall short. Artists in the “speech and silence” section explore the power and limits of language. Abdoulaye Ndoye, Adam Pendleton, and Theaster Gates used the written word as a motif. Helina Metaferia reworked archival images to project from a void where Black women’s voices were muted. Sanford Biggers honoured subjects who can no longer speak for themselves in a sculpture from his BAM series on view. Tavares Strachan implicates viewers in the title of his work, We Are in This Together, eliciting them to respond.

A: How did you see LACMA’s commitment to expanding its collection of Black artists informing this exhibition? Could you speak to the importance of institutional support in amplifying the voices of Black artists on a global stage?

DL: Imagining Black Diasporas debuts 42 recent acquisitions from LACMA’s collection. 63 of the 70 works on view derive from the collection. These acquisitions demonstrate the museum’s commitment to investing in the work of Black artists. LACMA’s new David Geffen Galleries, which open in 2026, move away from the model of the 19th century encyclopedic museum. With no “front” or “back,” the one-level building removes hierarchy, giving works by world cultures equal prominence. Moving forward, LACMA will continue to expand its programming and collections of Black Diasporic art. Institutional support is essential to giving artists a platform and to sustaining their practice. I hope the model of making acquisitions toward exhibitions, rather than relying on loans, will become routine.

A: What do you hope viewers will take away from visiting the exhibition?

DL: One insight I hope viewers will take away is that diaspora, a word traditionally associated with displacement, signifies creation and connection too. People reinvent their heritage through art. I hope viewers will leave with a sense that people are interdependent.

Imagining Black Diasporas: 21st-Century Art and Poetics is at Los Angeles County Museum of Art until 8 August 2025: lacma.org

Words: Emma Jacob and Dhyandra Lawson.

Image Credits:

1&4. Arielle Bobb-Willis, New Jersey, 2019, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Purchased with funds provided by the Ralph M. Parsons Fund.

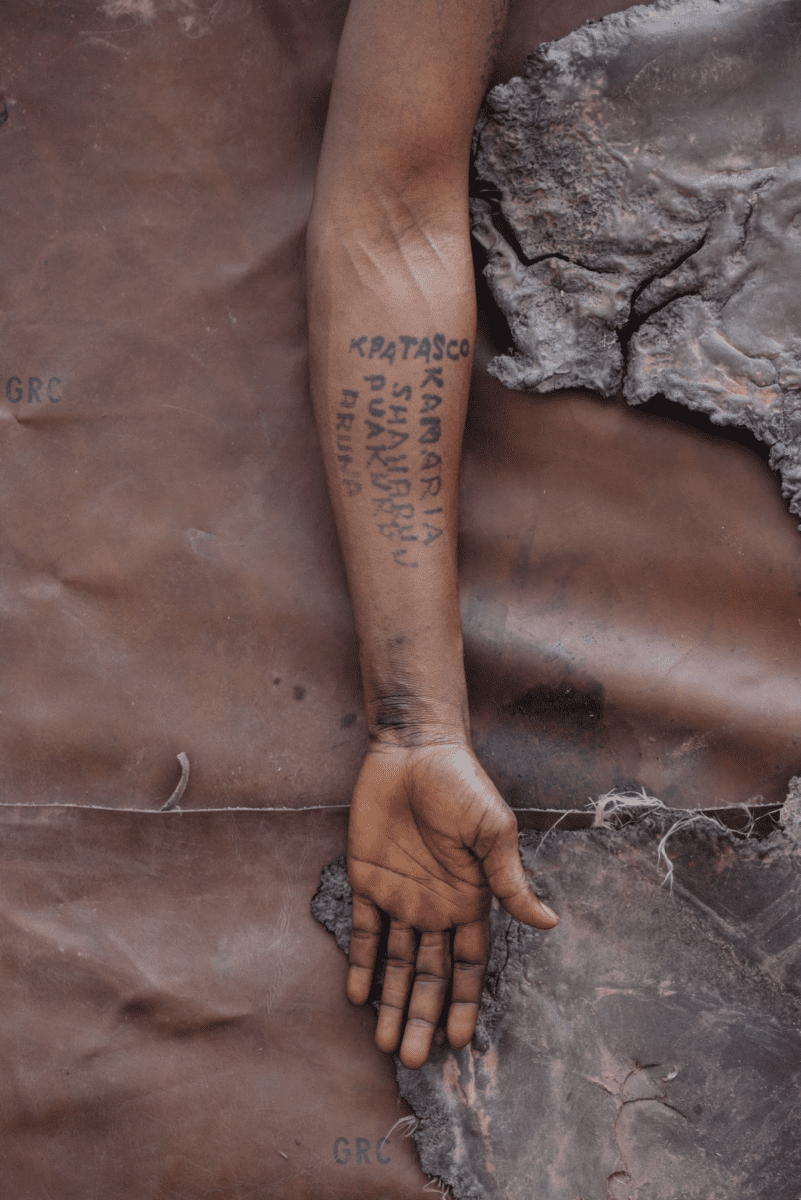

2. Ibrahim Mahama, KAMARIA KPATASCO GRC, 2019, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, purchased with funds provided by the Ralph M. Parsons Fund, © Ibrahim Mahama, photo © Museum Associates_LACMA.

3. Widline Cadet, Seremoni Disparisyon #1 (Ritual [Dis]Appearance #1), 2019, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, gift of Avo Samuelian and Hector Manuel Gonzalez, © Widline Cadet, photo © Museum Associates_LACMA.