How can architecture create a more inclusive and connected world? Bo Bardi’s structures offer lessons about how to rebuild and repurpose.

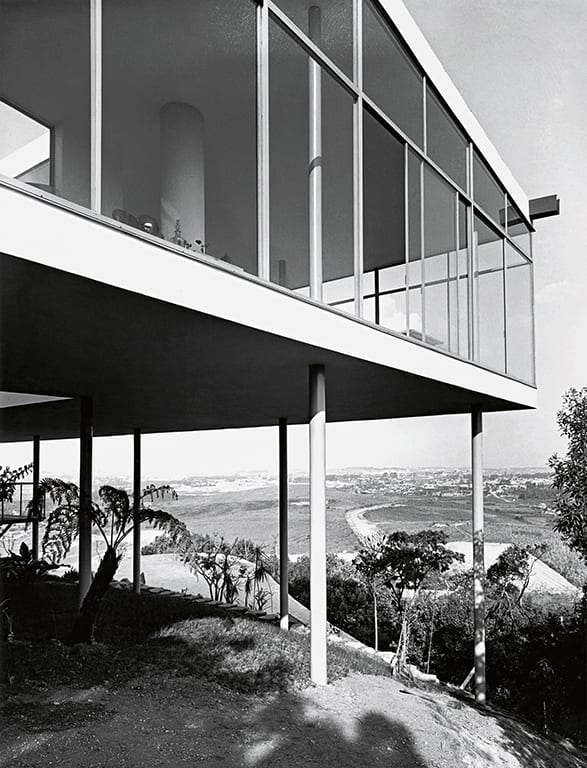

“In 1951, Lina Bo Bardi (1914-1992) built the Casa de Vidro, or Glass House, in the hills of what is now São Paulo’s wealthy Morumbi neighbourhood. Perched in the remnants of the Atlantic Forest, its long glass walls are not only surrounded by greenery, but actually wrapped around an interior courtyard of trees that Bo Bardi planted. Nature rises through the heart of the house, growing upwards through the centre of the structure, embracing pillars and staircases.

In Brazil today, deforestation of the Amazon has been legitimised by President Jair Bolsonaro. On a wider scale, the decimation of natural habitats and the destruction of biodiversity is, as researchers believe, creating conditions for new viruses to pass onto humans. At a time when the future of cities is uncertain – when doors are locked to the outside world – the legacy of Lina Bo Bardi (Née Achillina Bo), raises important questions about how architecture needs to change. Against a backdrop of the climate crisis and a global pandemic, how can we plan to live with the organic world in a more inclusive way? How should we live with each other?

A touring retrospective celebrating Bo Bardi’s career, titled Habitat, was planned before the Coronavirus outbreak, due to open at the Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago, on 13 June. “The idea for her was not to provide solutions but to encourage people to ask questions and to see difficult situations,” says Julieta González, curator of the show. “I think that we could all benefit from such an approach in the face of the crisis that we are living through today.”

Bo Bardi’s legacy goes beyond design, spanning cultural theory, museology, pedagogy, anthropology and theatre. However, the many strands of her practice are united by the fundamentals of community, survival and shelter. González notes: “Lina was an advocate of sustainability – of paying attention to local resources, both material and human. Her problem-solving approach empowered individuals and provided the tools for dealing with material hardship by making do with whatever means were available.”

This way of thinking was shaped by Bo Bardi’s direct experiences with war. In 1939, she left the Rome College of Architecture and moved straight to Milan. There, she worked as an architect, illustrator and editor at a time when, in her words, “nothing was built, only destroyed.” In 1943, the offices she shared with designer Carlo Pagani were blown to bits by an aerial bombardment. She would continue to see many more ruins in the years to come, not least in 1945, when she toured the south of Italy with Pagani and the photographer Federico Patellani, whilst documenting the devastation that they encountered along the way.

What can be built from ruin? How do we take devastation and decay and turn it into something meaningful, hopeful and helpful? Bo Bardi took these important questions to Brazil in 1946, a matter of months after she married the critic and curator Pietro Maria Bardi. She soon moved to São Paulo when her husband was invited to establish a museum of art in the city. In Brazil, Bo Bardi found a new starting point for architecture – one born from the memory of shelled-out buildings and makeshift refuges that she had witnessed in Europe. She reflected on structures in which the lines between inside and outside were tested and broken.

The Casa de Vidro was Bo Bardi’s first major architectural project, drinking from the well of Italian and American modernism that was prevalent at the time, but there are hints of something else at work. The house comes from a pre- or post-apocalyptic vision – a treehouse habitat where the walls are nearly transparent between the inhabitants and their surroundings: between civilisation and wild forests.

“When designing her house, she wasn’t just looking at the humans that would occupy the space,” says the architecture historian and theorist Beatriz Colomina, who, as part of the Habitat exhibition, co-authored an essay on Bo Bardi alongside the architect and theorist Mark Wigley. “She was taking account of all these other species. Plants, of course, are hugely important. This notion of paying attention to the non-human in architecture makes her totally contemporary.”

Wigley adds that this approach is political: it flattens a hierarchy, subverting a perceived order between “us” and “them.” He continues: “Bo Bardi crafts a philosophical position of another hospitality, in which you don’t privilege the human over the non-human, which then creates all sorts of transgressions of typical behaviour about gender and about technology.” It is this way of thinking that sets the Casa de Vidro apart from other modernist glass houses. If the likes of Ludwig Mies van der Rohe’s Farnsworth House or Charles and Ray Eames’ house are open to natural light but keep plants, insects and the elements at arm’s length, Bo Bardi’s Casa de Vidro contends with letting them in.

These are vital considerations for architects today, and not ones with easy answers. Conceptually, it’s all well and good to open the doors to your surroundings, but how do you protect yourself from what comes in? “The ethics of the non-human does take us directly into the Coronavirus,” says Wigley. “The concept of trans-species hospitality in her work is also about contagion. It is a philosophy of risk. So, immediately there is this question that we’re all asking as we withdraw into our bunkers and homes: what would Lina do?” Perhaps one way forward is not to limit the answers to the walls of our houses. Instead of asking how to best design our shelters, we should ask how to rebuild and repurpose the fabric of our cities, to safeguard communities whilst forging new public spaces out of pre-existing structures.

For Bo Bardi, these ideas were developed in the re-design of the Museu de arte de São Paulo (MASP). Built between 1957 and 1968, the iconic museum on Avenida Paulista is a vast glass and concrete box, suspended by four monumental pillars. The outdoor ground is minimal, with the exact same dimensions as the museum that hangs above it. Inside, the removal of barriers is even more evident. Bo Bardi hung the collection in glass panes; the public can see the interiors from the street. Within it, they can see the backside of the masterpieces. It is a porous institution fundamentally – an enormous vitrine that makes art visible in thrilling ways.

This anti-elitism would only grow in Bo Bardi’s career. The story goes that the architect’s interest in the northeast of Brazil, and its black African cultural heritage, signalled a crucial turn in her portfolio. There are those that dispute the extent of this shift. Beatriz Colomina and Mark Wigley, for example, claim that Bo Bardi’s outlook has ultimately been influenced by her earlier experiences with war. (“We say that everything you can see of Bo in Brazil you can already see in Italy” Wigley explains.) All the same, Bo Bardi moved to Bahia’s capital, Salvador, in 1959. There she went to work transforming a 17th century sugar mill into the city’s main cultural centre: Solar do Unhão. Designed with a central focus on pedagogy, it became a home for the city’s museum of modern art as well as the Museo de Arte Popular, which was full of objects made from tin, cardboard, wood and string. “By the time she moved to Bahia, Lina was no longer thinking in terms of European modernism and this was reflected in her work, not only in her conception of the Museo de Arte Popular in Salvador as an arts and crafts school, but also in her own design practice,” expands Julieta González.

These threads, of education, destruction, public space and renovation came together most powerfully in 1982 – towards the end of the military dictatorship in Brazil – with the opening of the Centro de Lazer Fábrica da Pompéia (Pompéia Factory Leisure Centre) in São Paulo. Now known as SESC Pompéia, this colossal community centre is built from the remnants of a steel drum factory, which was stripped and sandblasted to expose the reinforced concrete beneath.

In a move about as far from a glass house as you can get, the SESC Pompéia complex has gaping holes instead of windows, rendered deep red with sliding grills. It is hard not to see echoes of the destruction of war in its brutal openings, but even with these bold and alarmingly coloured elements, the building manages to be playful: a place of life rather than death. “There are many lessons to be learnt from that project, not only as a building but as an idea for a radical museum, a school, a leisure centre and a place for conviviality,” González notes. “The fact that it is so alive today, constantly in use and not just an iconic building of the 20th century, attests to the power of her vision.”

SESC Pompéia is a machine for community. Whilst it is temporarily closed during the lockdown, it is a testament to how the ruins of an old world can be repurposed for the new, bringing people together in a myriad of ways. The same can be said of Bo Bardi’s Teatro Oficina (1980-1991), a narrow, street-like theatre space for the company of the same name, built from the burnt-out shell of an earlier theatre.

Made out of painted scaffolding and simple wooden seats, its initial design came from the director Zé Celso, who experienced a vivid acid trip in which he hallucinated he was being trapped against a wall, on the run from the police. The Teatro Oficina is a theatre stripped bare. In an echo of the Casa de Vidro, the seats overlooking the stage also take in a bed of lush plants and a wall of glass windows. It is yet another project of Bo Bardi’s in which nature is not only allowed, but truly welcomed, inside, acting as a kind of healing antidote and a source of peaceful reflection.

“No one can save themselves by design,” Bo Bardi famously wrote in 1990. “Can a beautiful glass save us from thirst? Can a very beautiful dish or a beautiful plate save us from hunger, misery, illness and unemployment?” She recognised that design alone cannot deliver complete salvation, and as we stare into the coming months and years, it is worth remembering that the true task of architecture will be to reimagine political and social structures positively.

Bo Bardi’s philosophy of flattened hierarchies, communality for humans and the organic world, rings true at a time when so much about how we live has been thrown into turmoil. Perhaps the most valuable lesson for architects, and indeed the wider world, is to work with whatever means are available: not to see difficult situations as storms to weather, but as problems that are ready and waiting to be solved.

Thomas McMullan

Habitat is available from Prestel

Exterior view of the Glass House, 1951 (Photo: Henrique Luz) © 2020 Museu de Arte de São Paulo, Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago, Museo Jumex, and Prestel Verlag, Munich • London • New York

MASP, Avenida Paulista, 1968 © 2020 Museu de Arte de São Paulo,

Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago, Museo Jumex, and Prestel Verlag, Munich • London • New York.

Lina Bo Bardi, Oceanfront Museum: photomontage of the model and beach site, 1951. Impression on photographic paper, (Photo: Henrique Luz )18 x 20.5 cm.

Collection of theInstituto Bardi/Casa de Vidro, São Paulo © 2020 Museu de Arte de São Paulo, Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago, Museo Jumex, and Prestel Verlag, Munich • London • New York.

Lina Bo Bardi at the Glass House, 1952 © Niemeyer, Oscar / AUTVIS, Brasil, 2019. © 2020 Museu de Arte de São Paulo, Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago, Museo Jumex, and Prestel Verlag, Munich • London • New York