A sense of rhythm pulses through Music + Life, the major new retrospective of Dennis Morris’s work at The Photographers’ Gallery. More than four decades of imagemaking unfold across the gallery’s floors, offering a rich visual score composed of music, movement, rebellion and community. The show brings together iconic portraits and lesser-known documentary works to explore how Morris – British-Jamaican, self-taught and uncompromising – has chronicled the spirit of sound and the soul of Black British experience.

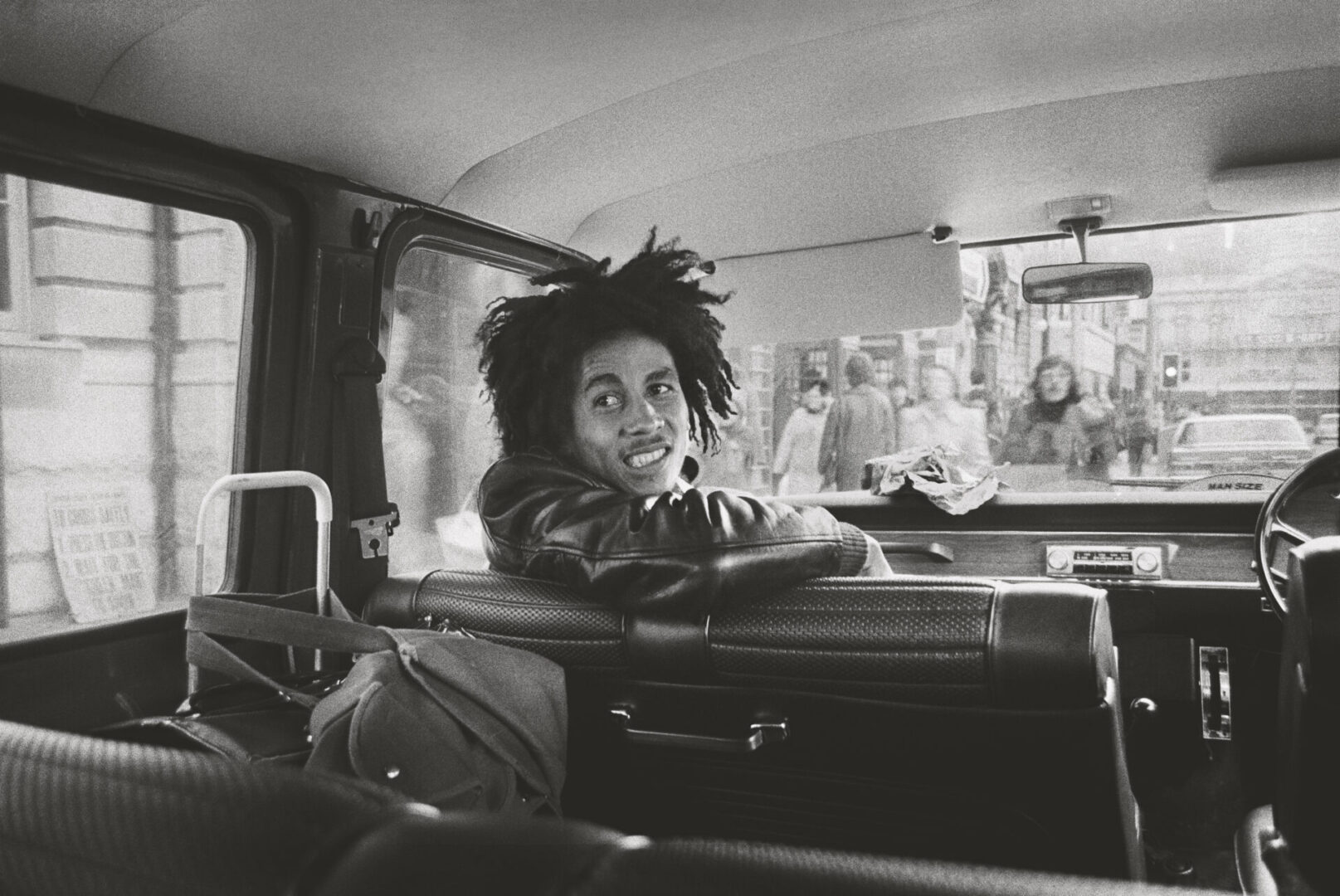

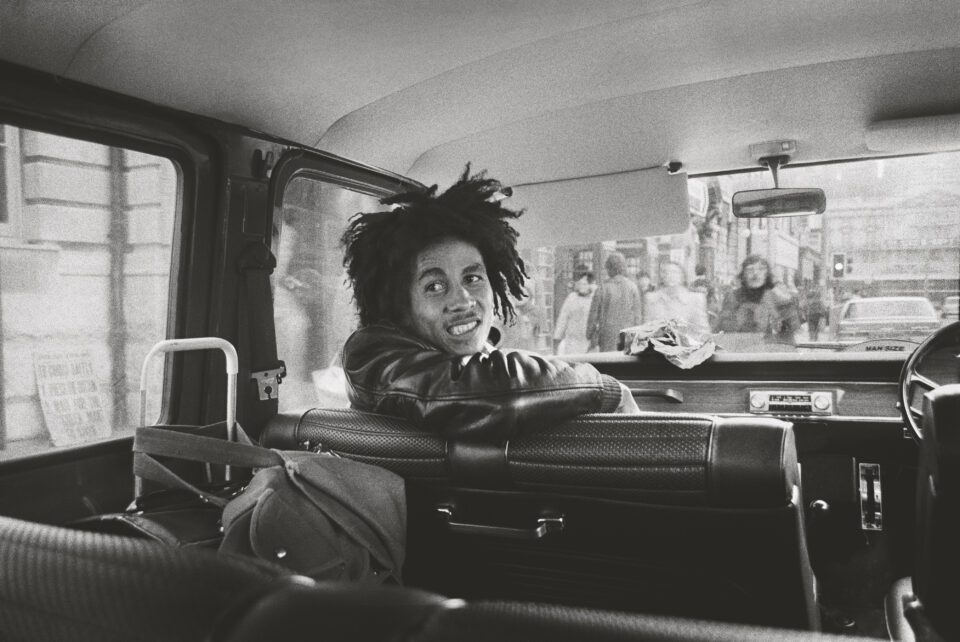

At the heart of the show is Morris’s deep creative relationship with Bob Marley. Their first meeting – a chance encounter when Morris was just 14 – set in motion a lifetime of collaboration. The photographs that followed offer rare access: Marley on stage, in prayer, resting, laughing – moments that speak to trust, rather than spectacle. As Morris recalls: “It was much more than just taking the photos. It was a teaching, a learning, a growing.” That sensibility carries across Music + Life, where the photographer’s lens functions less as an observer and more as a participant in the cultural movements he captures.

This exhibition arrives at a fertile moment for The Photographers’ Gallery. Earlier this year, the Deutsche Börse Photography Foundation Prize 2025 spotlighted conceptual and politically charged image-making, while Peter Mitchell: Nothing Lasts Forever offered a quietly surreal chronicle of urban transformation. Alongside Music + Life, the gallery presents Felicity Hammond: V3: Model Collapse – a speculative, post-digital vision of cities in flux – and in the Print Sales Gallery, Alma Haser: Everything has an End, Only a Sausage has Two plays with the uncanny in family portraiture. Together, these shows point to a curatorial commitment that embraces photography’s ability to reflect, critique and reimagine social reality.

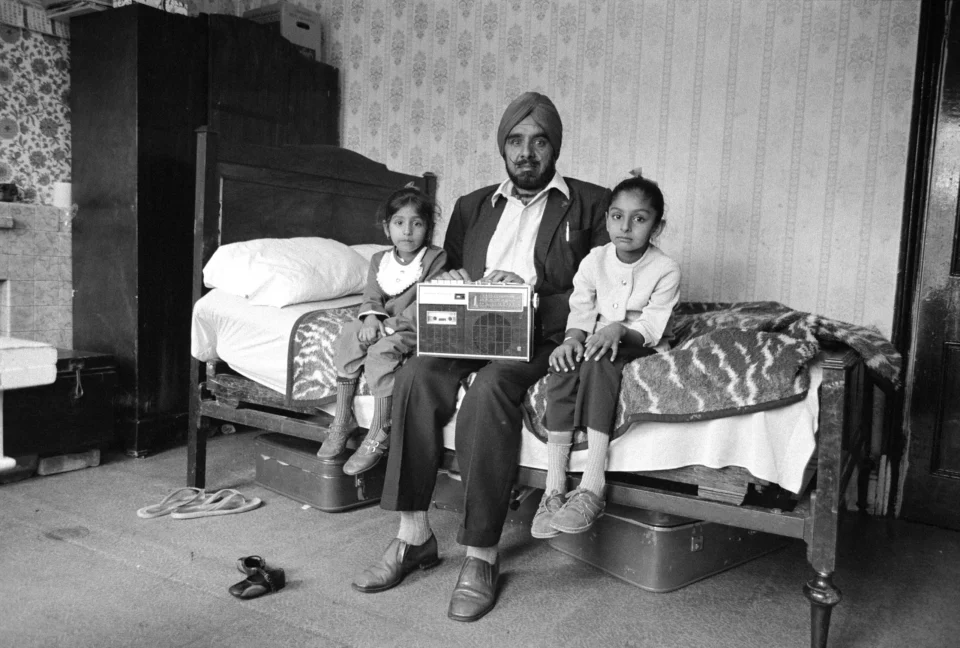

Returning to Morris, the full scope of his practice is revealed in the pairing of famous faces and street-level scenes. From reggae pioneers Lee “Scratch” Perry and The Abyssinians to punk icons like John Lydon and The Slits, the show celebrates a cast of musicians who redefined sound and style. But it is in the quieter series – Growing Up Black, Southall, and This Happy Breed – that Morris’s eye for human dignity shines most clearly. These images, often shot in church halls, living rooms or makeshift home studios, document the fabric of multicultural Britain in the 1970s and 1980s. “I was actually very shy,” Morris has said, “but with a camera in my hand I felt untouchable … you find a way to be invisible.”

That invisibility becomes a form of presence – allowing moments to unfold organically, without performance. In one frame, children gather at a South London street party; in another, elders greet each other outside a church. These are images of ritual and rhythm, both sacred and ordinary. The everyday becomes a site of strength, and photography a means of cultural preservation. Morris captures communities in transition, resisting invisibility through representation on their own terms. His legacy aligns with that of artists like Ming Smith, whose luminous black-and-white portraits foreground Black interiority and artistic life; or Jamel Shabazz, who turned the streets of 1980s Brooklyn into a canvas for affirmation and style. More recently, British photographer Liz Johnson Artur’s work shares Morris’s commitment to intimacy, working closely within diaspora communities to produce portraits that are both deeply specific and broadly resonant. Like these artists, Morris understands photography as a form of kinship – a way of honouring lives in motion.

Music + Life also acknowledges Morris’s contributions beyond photography. His design work – including Public Image Ltd’s iconic Metal Box and album artwork – reveals a broader visual intelligence. These artefacts, displayed alongside the images, underscore the interconnectedness of music, identity and aesthetics in his practice. Punk’s raw energy, reggae’s deep spirituality, and the visual codes of resistance all find expression here, often within the same frame. An archive of lived experience emerges, building a visual ecosystem in which culture, memory and music circulate. The works on view do more than commemorate. They ask you to listen to basslines, lyrics and unspoken histories. The show’s staging echoes this intent. Images are grouped thematically, not chronologically, allowing viewers to trace resonances across time and genre. The atmosphere is immersive without being didactic. One can drift from a photograph of Marley in quiet reflection to a confrontational portrait of Sid Vicious, and on to a crowded church gathering in Hackney. The effect is cumulative – a portrait of Britain seen from the inside out.

Dennis Morris has always been attuned to disruption and belonging, to both rupture and resilience. In an age of ever-accelerating image culture, his work reminds us of photography’s capacity to dwell, linger, testify and celebrate. Music + Life is a powerful retrospective, but it also feels like a reintroduction. Here is an artist whose archive still speaks urgently to the present. As the exhibition continues through September, it offers more than nostalgia or mythmaking. It invites reflection on who gets seen, how memory is shaped, and where music lives – not only in sound, but in contemporary culture.

Dennis Morris: Music + Life is at The Photographers’ Gallery until 28 September: thephotographersgallery.org

Words: Shirley Stevenson

Image credits:

1&4. Dennis Morris, Babylon by van, London, 1973. © Dennis Morris.

2. Dennis Morris, Shopping for the Trenchtown kids, Leeds, UK, 1974 © Dennis Morris.

3. Dennis Morris, Man with his two daughters and his prized possession, Southall, 1976 © Dennis Morris.