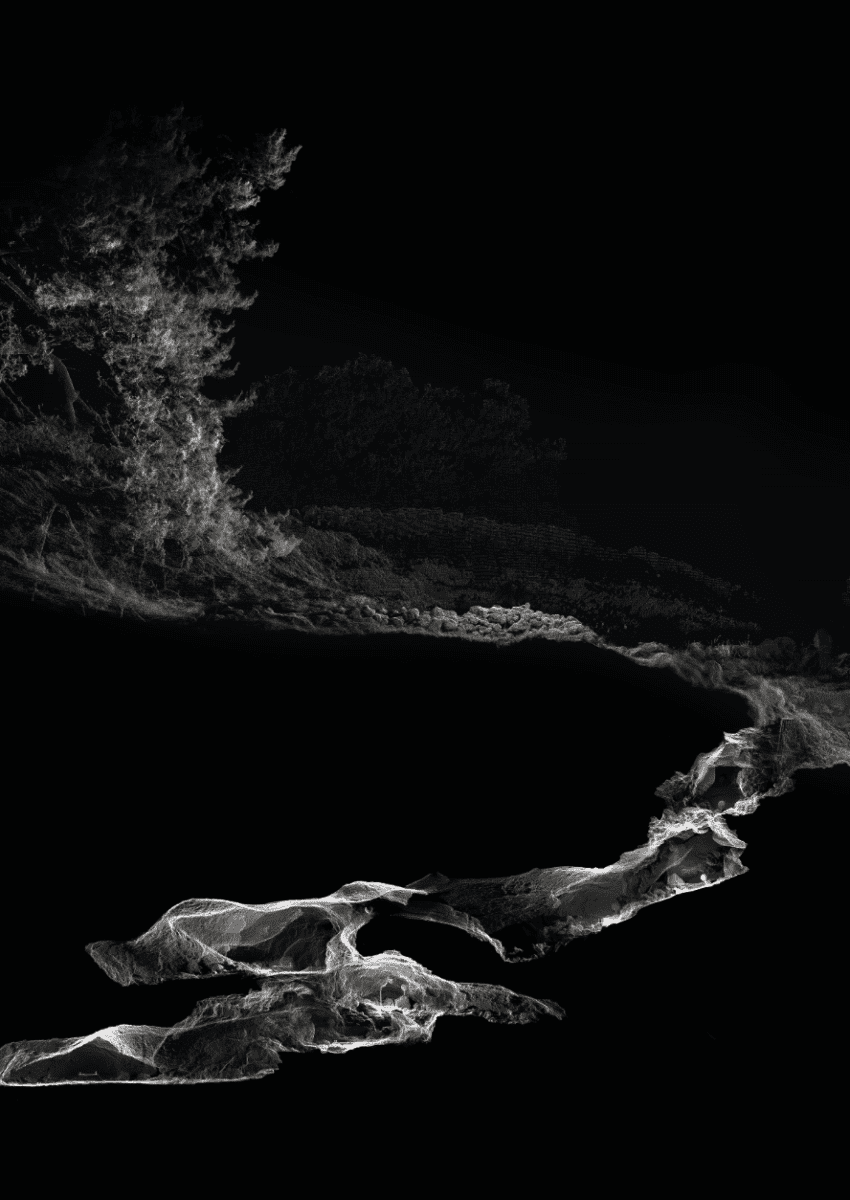

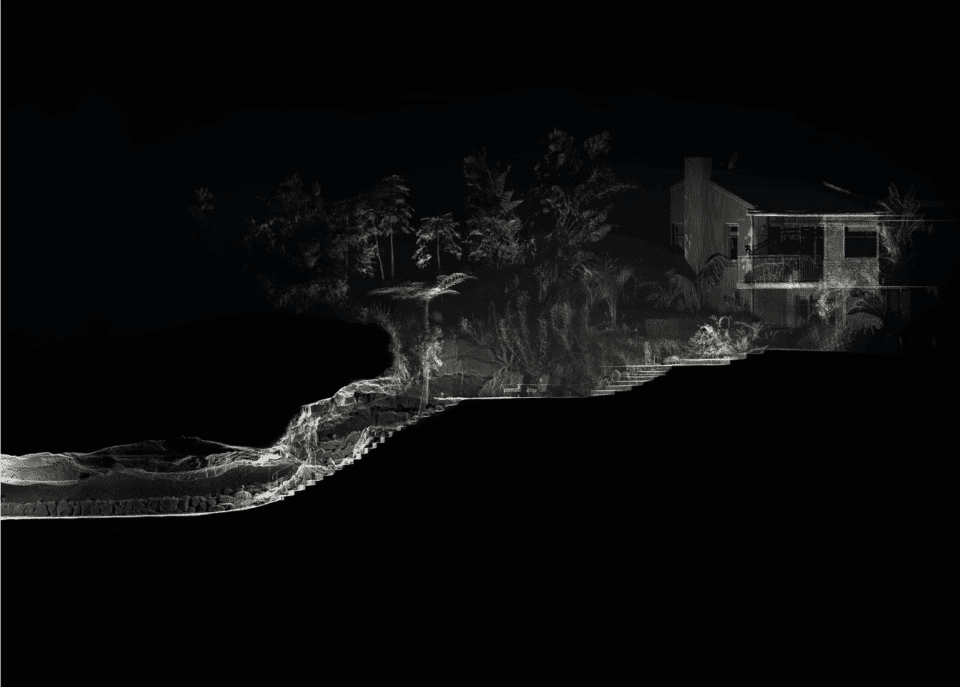

Auckland sits on an active volcanic field; ancient networks have been formed by lava. Chirag Jindal’s images examine these hidden landscapes and caves.

LiDAR (Light Detection and Ranging) or 3D laser scanning, was conceived in the 1960s for high-resolution topography mapping. The involves firing pulses of laser light at a surface, some at up to two million pulses per second. A sensor measures the amount of time it takes for each pulse to echo back, creating a virtual “point” accurate to less than 1mm. By repeating this process in quick succession, the instrument builds up a “point cloud” – a precise, digital replica of reality.

Chirag Jindal (b. 1993) is an artist and surveyor working at the intersection of documentary journalism, new media art and contemporary cartography. Jindal began exploring the role of terrestrial LiDAR as an emerging medium for pho- tographic documentation, after graduating with a Master’s Degree in Architecture in 2016. Into the Underworld / Ngā Mahi Rarowhenua, employs this technique to document hidden lava caves under the city of Auckland. The caves are unique to the volcanic region and are considered wāhi tapu (sacred) to local Māori groups. Jindal’s practice focuses on humanity’s relationship to marginalised landscapes, exploring heritage, narrative and collective memory through mapping and archiving. This ongoing series has won multiple awards, including the 2020 Royal Photographic Society Under 30s Award and the Bialystok Interphoto Grand Prix. Jindal was also longlisted for the Aesthetica Art Prize in 2020.

A: How did you come across LiDAR technology, and when did you begin learning how to use it?

CJ: In our final thesis year, there was a call for students to get involved in a summer project to “scan” a historic neo-gothic church in downtown Auckland. The School of Architecture had just acquired an old LiDAR scanner from the Department of Anthropology, and wanted to test out a new approach to document the city’s heritage. I remember being captivated by the process, seeing the rooms – walls, floors, ornaments, paintings, textures – digitised in detail into RGB and XYZ points. Through the lens of the scanner, the world was re- duced to Cartesian coordinates, visualised in a three-dimen- sional space. It offered novel readings of space; to look back from impossible angles, through walls and surfaces, and flat- ten entire spaces into a single collapsed image. When the project was completed, I had some free reign to experiment further – mapping objects, buildings and landscapes that I found interesting. Back then, the instruments weighed over 15kg and needed a main power source, so it was laborious to set up and (funnily) limited by the longest extension cord I could afford. There weren’t many resources to train from, so there were a few long days and nights researching and self- learning. That was almost six years ago, and the technology has already come a long way since those early experiences.

A: What are the practical uses of this equipment, and how have these changed over the years?

CJ: One of the first recorded uses was in 1971 during the Apollo 17 mission, where LiDAR was used to map the surface of the moon. Since then, its development really has been driven by the need to quantify space and represent it digitally, beginning with large-scale topographical mapping from the air, to detailed land and building surveys from the ground. Whilst the medium has become almost ubiquitous in many forms (aerial, mobile, solid-state), the most common form today is terrestrial (ground-based) LiDAR – a technique now applied in documenting archaeological ruins, criminal forensics, computer vision, film location mapping, heritage and site analysis. Many of these appli- cations have only emerged over the past decade. Beyond measuring space, LiDAR is increasingly taking on a documentary role in new applications; an empirical approach to index reality, to archive it and revisit it in posterity. In the near future, I wouldn’t be surprised if everyone had power- ful scanners in our pockets. The latest iPads already fea- ture basic sensors, used to measure space for AR/MR apps. Eventually, LiDAR may be the way most machines “sense” the world; we’re seeing this in autonomous vehicles.

A: When did you start to think of LiDAR as a potential artistic process – something immersive and conceptual as opposed to purely technological or solution-based?

CJ: Part of this was realising that LiDAR could be an investigative technique. On the one hand it furnished evidence of something – to index it. Analogous to the early era of photography, it still has the innocence of an unfalsifiable medium, providing certainty of the subject with a scientific underpinning. Each of the millions of points in a single image is a kind of spatial fact – a scientific certitude. How- ever, there is also a second moment of creation. In the real world there’s the recording of the subject using LiDAR, translating it into digital data – a process that feels empirical, scientific and linear. The other is in the virtual world, looking back at the resulting point cloud. This process is more rigorous and artistic, akin to a photographer framing the subject. The data can be viewed from any angle, at any distance, at any focal length, at any crop. What can the data reveal that wasn’t previously visible? What is the right visual approach for this issue? What is shown and not shown? From what angle is it best represented? Is it best described through moving images, orthographic sections, fabricated models, virtual reality, or web-based experiences? If it is a particular section, where does the section line lie?

A: How do these questions inform your vision?

CJ: For me, the artistic merit of this medium lies in a wide possibility of questions and answers. Point clouds are inherently realistic, and yet otherworldly. They are at once geometrically exact, but also vaporous, at the overlap of reality and fiction. One of the first artistic explorations of this was in the music video for Radiohead’s House of Cards, which layered kinetic scans of Thom Yorke against false- colour backdrops of wide, urban point clouds. The video is a contradiction really, because on the one hand you are looking at a distorted representation of reality but under- pinning this is scientific data. You’re made to question the nature of the subject, all the while coming to terms with the reality of it. It’s the uncanny, but made to be accepted.

A: What did you want to uncover in Into the Underworld?

CJ: Into the Underworld / Ngā Mahi Rarowhenua began with me posing the following provocations: how do you make the invisible visible? How do you foster stewardship for a landscape that can’t be seen, or publicly accessed? Can we archive the landscape for posterity? How do we learn about the location of the sites? How do you gain the trust of landowners, local Māori, council and the wider community? Finally, if the issues warrant didacticism, to what extent does it lean on a museological approach? Given much of the landscape’s history is unpublished, is it possible to do this without assuming authority over the geography?

A: This particular series investigates an ancient network of caves beneath suburban streets. What is it about this subterranean landscape that sparked your interest?

CJ: Auckland sits on top of an active volcanic field. So, these sites aren’t at all like limestone caves – they were formed by the region’s ancient lava flows. This is one of the few places in the world where they exist. When inside, it’s powerful to witness the fossilised flows along the walls, floors and roof where the lava cooled into rock. Despite this, the caves are not at all common knowledge and exist out- side the public realm. Auckland is a young city, and over the past two centuries of urban sprawl there hasn’t been any legal framework protecting the sites. So, the majority of these caves have become polluted or filled with road and construction debris. Their relationship to the urban environment is extraordinary, stretching underneath suburban homes, tree-lined streets, local parks, gas stations and private schools, thresholded by manholes, backyard grottoes and street front garages. They lie underneath the legal boundaries of private property, limiting entry to trespassers and spurring vague understandings of ownership and kaitiaki (stewardship). Any new discoveries continue to be filled by developers without any policing, and at this rate most caves will likely be lost by the end of the century.

A: How important is the aesthetic? How do you feel that the ghost-like outlines are representative of a heritage that’s being lost to urban development?

CJ: Auckland is in the middle of a housing crisis. It has been for the last decade or so, and the result of this is large swaths of land converted from farmland and wilderness to repetitive, homogenised tract housing. The city is built amongst 53 unique volcanic cones, and yet half of these have been quarried away. We are surrounded by heritage and identity, and yet we still end up with these cookie-cutter streets. In my work, the caves take precedence, magnify- ing the detail and textures of ancient, fossilised lava flows. This is in subtle contrast to the surface – distant and temporary. The landscape below is tens of thousands of years old, whilst the built environment above has an expiry. In reality, many of these old brick and tile dwellings will soon be replaced by two or three-storey townhouses. It’s likely that, when this happens, the caves may become totally destroyed or inaccessible. The tree at the backyard of Shackleton Road has already been removed – the site was subdivided not long after the scan was done, and the entrance to the cave has been sealed. I ask: how do we want to relate to these sites in the future? What is Auckland’s vernacular?

A: How will the series develop moving forward?

CJ: The project has gained attention. Recently, I’ve received enough funding to document a further 10 sites in 2021. Through the legitimacy built over the past five years, we’ve also been invited to work more closely with local iwi groups, including sites that are tapu and require formal protocol. The project will likely be ongoing for several more years.

Words: Kate Simpson

RPS International Photography Exhibition Touring throughout 2021.

rps.org | instagram.com/_chiragchirag

Images:

1&6. Chirag Jindal, no.09 Landscape Road, 3500mm x 1220mm (crop). 2018.

2. Chirag Jindal, no.01 Shackleton Road, 6500mm x 1220mm (crop). 2018.

3. Chirag Jindal, no.12 The Uncanny, 1500mm x 1500mm (crop). 2018.

4. Chirag Jindal, no.02 Ngātiawa Street, 3500mm x 1220mm (crop). 2018.

5. Chirag Jindal, no.07 Anā Kōiwi (Cave of Bones), 2500mm x 1500mm (crop). 2018.