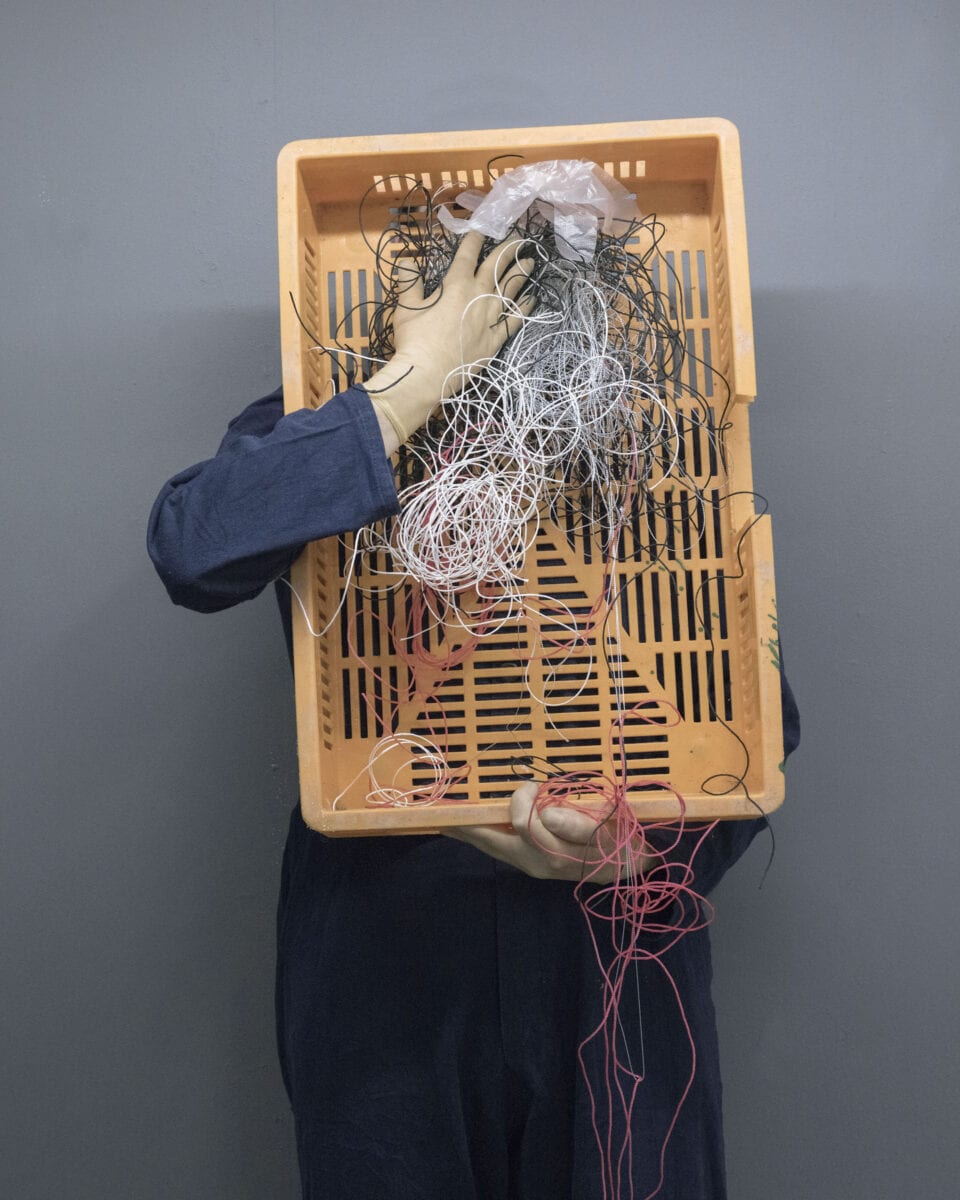

For her latest exhibition Field Test, photographer Jackie Nickerson (b. 1960) has wrapped the human form in elaborate, unwieldy costumes made of waste plastic. Limbs are immobilised and faces obscured, suggesting a loss of freedom and identity. In other images, impersonal locations such as airports are glimpsed through tinted windows, or photographs are pictured shrouded in layers of plastic. This powerful sequence offers stark messages regarding human beings’ relationship with technology and nature, and the seductive and destructive effects of consumerism. Aesthetica spoke to Nickerson about the new show.

A: You have draped human bodies in industrial and waste plastics. What led you to this focus on concealing the body and face?

JN: The non-literal portraiture follows on from my earlier show Terrain, in that it deals with the idea of physical and psychological memory mechanisms that cause morphological adaption. I actually began Field Test as a conceptual documentary series, travelling to relevant locations in Europe and America, but that didn’t work for me. I tried using many different types of imagery, but I wanted the work to have a visceral effect, so in the end I knew that I would have to work with real human beings in order to achieve this.

A: What, if anything, is significant about the materials you have chosen? For example, is there an ecological message here and if so, what would you say it is?

JN: This series addresses the unseen, a reality that is covert. It addresses a kind of collective trauma and anxiety. I used materials that are quotidian, everyday things that are an intrinsic part of our lives; semi-transparent PVC coated polyester mesh, recycled and new agricultural plastics such as knitted polypropylene shade netting and polystyrene packaging. Most of these materials have a duality: there’s single-use plastic such as PPE and single-use plastic such as drinking straws. It’s just asking a question about our personal choices. There is an ecological cost to our use of plastic (and all fossil fuels), and our food and agricultural choices.

A: The emotional anonymity of the models contrasts with the impression of physical uprightness or alertness. Are there allusions here to the modern world of work?

JN: I wanted the models – let’s call them figures – to have a human presence but not project or engage with the viewer in any direct way. So they were there but not present. I felt like there had to be an element of acquiescence here, of suffocation and anonymity. I was thinking of the figures as representative of all of us living here in the present.

A: Another recurring theme is screening or concealment: whether by masks around the face or blackened-out airport windows. What is the significance of this screening of subject matter?

JN: For me it addresses what is seen and what is unseen, and how that affects our lives. It’s like gravity – we all know it’s there but we can’t see it and we forget about how powerful it is. I started to think about all the unseen things in our lives that encroach on our rights, such as data mining and genome editing. We know it’s there but we don’t think about what the long term effects are. And these are transformative technologies. So the mesh, the semi-opaqueness, the grids – all-evident in everyday materials – addresses this.

A: You refer in an interview accompanying the show to our relationship with non-human animals. Do you feel this theme is consciously broached in these images?

JN: We share the planet with thousands of other species but anthropocentrism will, probably, ultimately kill us all. I address this in one piece in the show, Brown Hyaena, a photograph of a dead, stuffed wild Hyena that I made in the Natural History Museum in Bulawayo in Zimbabwe, inserted into a black plastic piece of meat packaging.

A: In an essay on your work, Aidan Dunne notes that “it takes a lot of energy and ingenuity to become and remain digitally invisible.” How is the theme of digital visibility/invisibility broached in your work?

JN: This idea of digital visibility versus digital invisibility is a question about choice. If we choose to engage with the world, what are our choices? Can we do this without the internet and all the issues that surround our engagement with the internet and our privacy and human rights? Using the internet isn’t free. We are all monetised. The semi-opaque or covered figures allude to this duplicity, the dichotomy in all our lives. It’s about the technological choices we make in a new world.

A: How else would you describe the work in this show?

JN: These images are symbolic. I am trying to make images of something that doesn’t exist. Like a law of physics. What I am trying to address is a feeling, an underlying anxiety that is hard to define. The sense that new technologies are not being held accountable for the transformative impact on all our lives, the lack of an open, democratic conversation that address these issues, and the day to day psychological and ecological effect they have on us.

Field Test is showing at Jack Shainman Gallery, New York, until 3 April.

The accompanying publication by Kerber was released in October 2020.

Words: Greg Thomas

Image Credits: All images courtesy Jackie Nickerson and Jack Shainman Gallery.

1&7: Isolation, 2019

2. Cloud, 2019

3. Crate, 2019

4. Grey Head II, 2019

5. Supermarket Mask, 2019

6. Clear Head, 2019

7. Wrapped, 2019