German artist Benedikt Partenheimer (b. 1977) uses concept-led photography and subtle optical tricks to reveal the invisible effects of climate change. A new book from Hatje Cantz, The Weather Is Fine, gathers together a career’s worth of such images. The most disturbing and iconic series in the book is perhaps Particulate Matter (2014), made by travelling to areas of China where the Air Quality Index is described as “hazardous”: that is, likely to cause “serious aggravation of heart or lung disease and premature mortality in persons with cardiopulmonary disease and the elderly; serious risk of respiratory effects in general population.” In these smog-drenched shots of Shanghai, Beijing and other hubs of the Chinese economy, sunlight is swamped in particles of pollution and the outlines of roads and buildings become almost invisible, as if they too were gradually dissolving in the particles of acid, chemicals, metal and dust.

The eerie beauty of these works is reminiscent of the painter James McNeill Whistler’s (1834-1903) famous Nocturnes, which show the smog-drenched banks of the Thames dancing with hazy light at night. Partenheimer remind us of art’s complex relationship with urban and economic growth, but more than that, the otherworldly quality of his images suggests that the viewer has stumbled onto the surface of some distant planet, with atmospheric and sensory qualities quite different to our own. The effect of alienation makes us realise the sheer scale of the changes we are wreaking on the climate. As the artist notes, remembering a winter day in Shanghai: “the scene is beautiful and terrifying at the same time.”

Throughout the rest of the text, a number of visual techniques are used to bring home the realities of climate crisis across the world. In Memories of the Future (2017), the artist worked with scientists in Alaska to identify areas of permafrost that were thawing out, leading to the release of methane and carbon into the atmosphere. By setting fire to bubbles of gas as they escaped from the surfaces of frozen lakes, Partenheimer was able to make a concise yet powerful visual point, forcing us to confront the imperceptible damage being done to remote areas of the planet. Other shots from the same series show “drunken trees,” dismantled from their vertical positions by the unstable thawing earth beneath.

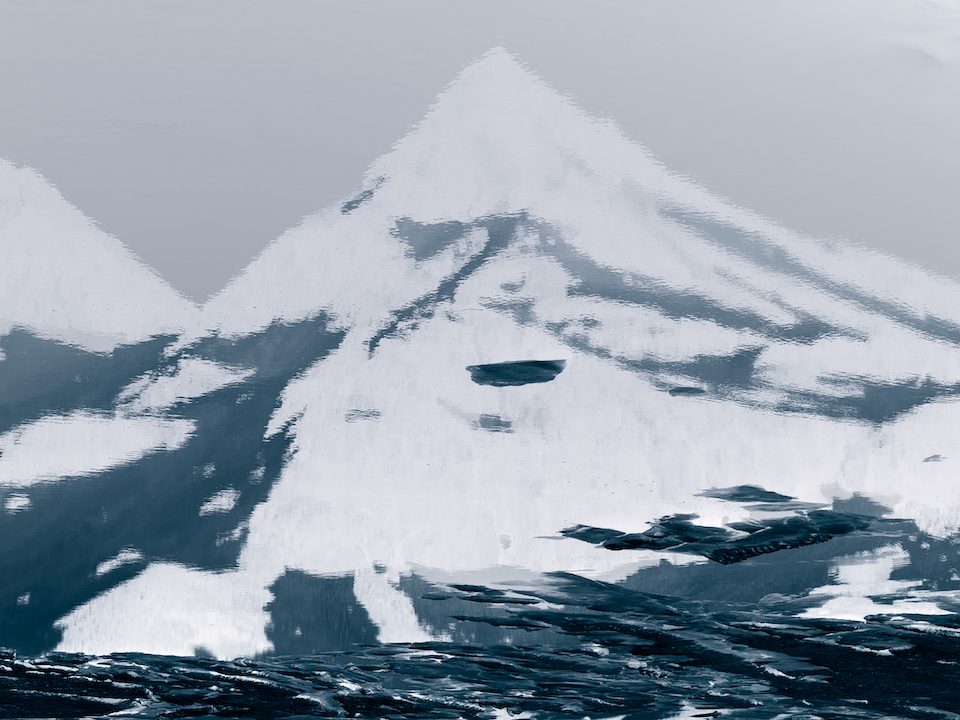

Elsewhere in the book we find a spectacular reproduction of the first US nuclear arms tests from 1945, one convincing marker for the beginning of the Anthropocene, and images of melted glaciers forming new lakes in the mountains of Austria. But one of the most interesting projects Partenheimer has undertaken is also the smallest in scale. In 2012 he travelled to Japan to photograph some of the country’s six million vending machines: Japan’s automated service industry is the most advanced in the world, its cities lit up at night by networks of glowing rectangular boxes.

These nocturnal environments seemed to contain some ghostly human presence—vending machines are, of course, roughly the height of people. Meanwhile, light energy pours out in waves onto vacant streets and lots. It’s a reminder of the power of the economic systems human beings have established to generate endless cycles of consumption and waste even when there is no-one there to benefit. The system takes on its own logic; the system wins. All the artist can do is chart the ensuing storm.

The Weather Is Fine is published by Hatje Cantz, 2021. Find out more here.

Words: Greg Thomas

Image Credits:

1. Reflection from the series Glacial Water 2019 © Benedikt Partenheimer

2. Shanghai 2014from the series Particulate Matter © Benedikt Partenheimer

3. Methane Experiment Alaska 2017from the series Memories of the Future © Benedikt Partenheimer

4. Trinity 2016 © Benedikt Partenheimer

5. Reflectionfrom the series Glacial Water 2019 © Benedikt Partenheimer