A major new touring exhibition promises to shed light on the hidden histories of women’s sculpture in the UK and worldwide. The Arts Council Collection, from which the exhibits are drawn, describes Breaking the Mould: Sculpture by Women Since 1945 as “the largest survey of its kind to date”. The show challenges the male-dominated narratives of post-war British sculpture, presenting work that pushes boundaries.

Ahead of a talk at the 2021 Future Now Symposium, Aesthetica speaks to the show’s curator, Natalie Rudd, about this vital intervention in modern art history.

A: Why is this exhibition so important, thinking about the history of women’s participation in sculptural movements in the UK and worldwide?

NR: There have been many survey exhibitions of British sculpture that have sidelined or overlooked the contribution made by women. Given the Arts Council Collection holds over 250 sculptures by more than 150 women, we feel we are ideally placed to address this. This exhibition feels particularly timely given 2021 marks the 70th anniversary of the Arts Council Collection. The intention is to bring the work together to assess shared strengths and concerns, but also to trace moments of independent departure. We hope to prompt a conversation about what women have introduced to the field of modern and contemporary sculpture, whilst also reflecting upon some of the challenges and obstacles they have faced across time.

A: What can viewers expect to find when they visit the show?

NR: I think one thing that will be immediately apparent to visitors is the strength, dexterity and range of the work on display. Together, the works evidence a vast range of materials, processes and ideas played out across a breadth of scale from the miniature to the monumental. The selection is deliberately broad and inclusive, with works grouped into loose thematic sections. This structure provides a really interesting intergenerational approach, with works appearing to ‘speak’ to one another across time. The formal properties of an early piece, for example, might chime with a more recent acquisition in unexpected ways, sparking new ideas and ways of thinking about modern and contemporary British sculpture.

A: The first work by a sculptor to be purchased for the Arts Council Collection was a drawing by Barbara Hepworth in 1947. How important is Hepworth to the story of modern sculpture in Britain?

NR: It is wonderful to be able to include Hepworth’s drawing, Reconstruction, as it enables us to reflect on Hepworth’s influence, even before the Collection had decided to pursue the acquisition of sculpture in any strategic way. Hepworth was certainly a pioneer in terms of achieving significant international attention when many women were finding it difficult to maintain any kind of foothold within the field of sculpture. Hepworth set a very high benchmark in terms of what might be possible, both in terms of scale and ambition, but also with regard to the success she achieved in her own lifetime. This legacy is of huge importance even to those artists who have gone on to pursue very different ideas and ways of working.

A: There is a huge array of work included, from St. Ives School abstraction to concrete and kinetic artists, through to YBA-associated sculptors and contemporary names working across a vast range of styles and movements. Do you feel there is a stylistic thread that holds it all together?

NR: The exhibition is deliberately diverse in that we didn’t want to typecast or to make assumptions about the type of work that women make. That said, in bringing the work together, a number of striking themes are starting to emerge. A key theme concerns the frequent employment of vulnerable materials, from dying flowers to salvaged blankets and cast absent spaces. These materials sometimes combine with precarious display methods including propping, stacking and leaning. Another emerging theme is that of lightness and weight. Wendy Taylor’s work, Inversion, for example, embodies both properties: a weighty form is chained to the floor yet at the same time it appears to levitate. The exhibition reveals how women have pushed British sculpture in many new directions. Overall, it should be acknowledged that there is still a lot of work to be done to increase research into these practices, and to secure visibility for these works beyond the life of the exhibition.

A: What was the motivation behind asking artists, curators, and community groups to provide labels for some of the works?

NR: It was really about building on the idea of an intergenerational conversation, but also about embracing a range of expertise. We wanted to hear from artists, writers and curators, but we also wanted to invite students and members of the community to share their thoughts and opinions. The wider objective is to nurture a sense of ownership and engagement: the Arts Council Collection belongs to everyone and exists to be shared and discussed.

A: Can you explain a little bit more about the three thematic sections into which you have grouped works (“figured, formed, and found”)?

NR: A chronological presentation felt too fixed and canonical, so we opted for a gentle thematic approach. The exhibition starts with the Figured section, which features a range of approaches to sculptural figuration spanning 75 years. The first sculpture to be acquired for the Arts Council Collection was a very classical reclining terracotta figure by Karin Jonzen in 1951. Since then, artists have explored the body in a multitude of ways, using bronze, steel and wood and even stuffed tights or human hair. The Formed section is equally dextrous, with huge material leaps from mirrored surfaces and painted wood, to paper, kinetic sculpture and painted surfaces by artists including Rana Begum and Eva Rothschild. Finally, the exhibition at Longside Gallery ends with Found, which explores the significance of salvaged objects by artists including Veronica Ryan, Anya Gallaccio and Helen Marten.

A: Can you name some contemporary women sculptors whose work you’re particularly excited by?

NR: The show includes a wealth of amazing and only recently acquired work by artists including Katie Cuddon, Grace Schwindt and Hayley Tompkins, among many others. It is wonderful to be able to present their work at Longside Gallery for the first time since acquisition. It is also encouraging to reflect on the fact that many other sculptures by women have been acquired since the selection was confirmed. The acquisitions committee has been addressing ‘gaps’ in the Collection through the recent, retrospective investment in work by artists including Shelagh Cluett, Gillian Lowndes and Margaret Organ. Thinking ahead, I feel very strongly that Breaking the Mould must act as a catalyst, prompting a wider set of objectives to increase visibility across the Collection.

Breaking the Mould: Sculpture by Women Since 1945 opens at the Longside Gallery, Yorkshire Sculpture Park on 29 May. From September onwards it will travel to four further venues across the UK, closing on 12 March 2023. Find out more here.

At the Future Now Symposium 2021, Natalie Rudd, Senior Curator, celebrates those who have contributed to modern and contemporary sculpture, including Rana Begum, Holly Hendry and Permindar Kaur. The talk highlights Arts Council Collection’s commitment to reflecting diversity, and is led by Holly Trusted (formerly Marjorie Trusted), V&A.

Friday 30 April | 18:15-19:15 | Book Your Place Here

Words: Greg Thomas.

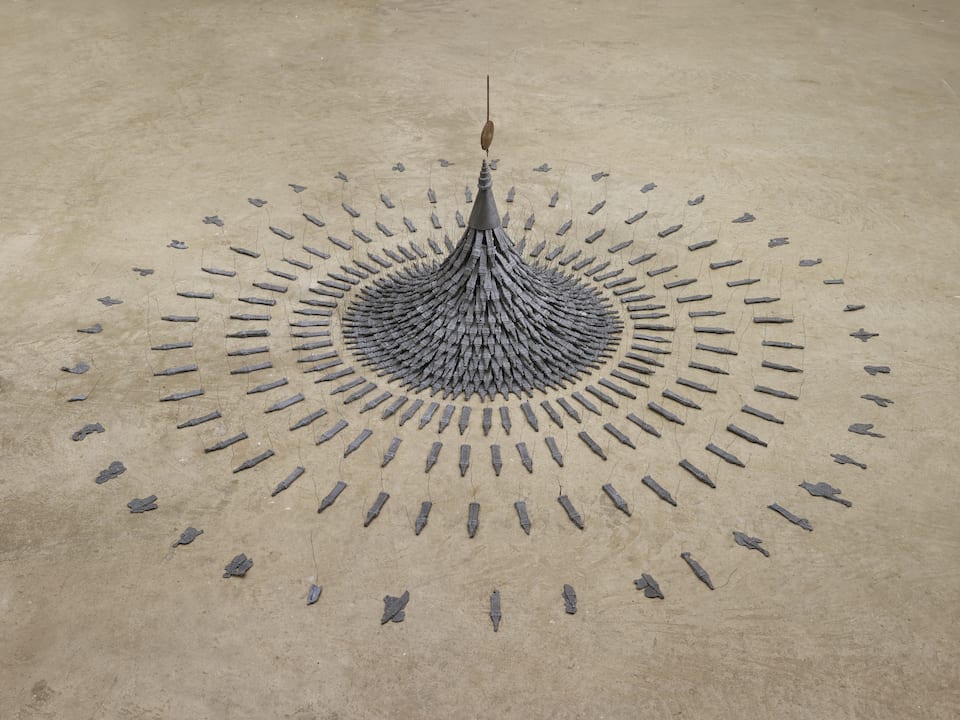

Image Credits:

1. Lygia Clark, Animal 3, 1969. Arts Council Collection, Southbank Centre, London © the artist

2. Barbara Hepworth, Icon, 1957. Arts Council Collection, Southbank Centre, London. © Bowness

3. Kim Lim, Samurai, 1961. Arts Council Collection, Southbank Centre, London. © Turnbull Studio

4. Cornelia Parker, Fleeting Monument, 1985. Arts Council Collection, Southbank Centre, London © the artist.

5. Sarah Lucas, NUD CYCLADIC 7, 2010. Arts Council Collection, Southbank Centre, London © the artist Purchased with the assistance of the Art Fund.

6. Margaret Organ, Loop, 1978. Arts Council Collection, Southbank Centre, London © the artist.