“Sankofa”, in the Akan Twi language, means “to retrieve.” The term is, however, part of a much larger philosophical tradition which originated in Ghana, and continues to stretch across the wider African diaspora today. As a proverb, and transnational cultural phenomenon, the term can be translated as “it is not taboo to go back and fetch what you forgot”, or, in other words, “return to your past.” It is often represented by a bird turning its head to eat an egg from its own back.

“Sankofa” was crucial for British-Ghanaian writer and curator Ekow Eshun (b. 1968) when planning In the Black Fantastic at Hayward Gallery, London. “To move into the future, you don’t have to leave the past behind; the past and the future form a circle of some kind,” Eshun states. “One of the pernicious faces that our history of colonialism has left the developing world is the sense that the cultural heritages we have are less valuable than the beliefs and the cultures of the west.”

In the Black Fantastic is replete with sculptures, video art, collages, film stills, photographs, mixed-media artworks, paintings, installations and performances that draw from otherworldly themes: magic, mythical realms and creatures that transcend reality and conceptualise new forms of existence. Eleven practitioners – including Nick Cave, Sedrick Chisom, Ellen Gallagher, Hew Locke, Wangechi Mutu, Rashaad Newsome, Chris Ofili, Tabita Rezaire, Cauleen Smith, Lina Iris Viktor and Kara Walker – excavate the past to imagine new, metaphysical worlds of Black existence. In these visions, individuals can live beyond the structures of colonialism, white supremacy and the legacy of the transatlantic slave trade.

Sometimes, these worlds are located deep underwater, swimming in an alternate narrative, as in Ellen Gallagher’s series Ecstatic Draught of Fishes (2019-ongoing), which captures, in dreamy, ethereal watercolour paintings, a “Black Atlantis” wherein enslaved people that have been thrown overboard in the Middle Passage survive beyond the depths and build an oceanographic kingdom. In other artworks, we skyrocket into the future and a vast abyss of stars, leaving earth behind for more fortuitous galaxies and possibilities, as in Yinka Shonibare’s life-size sculpture Refugee Astronaut II (2016). This haunting figure hauls pots, pans and furniture in a fishnet parcel on his back, permanently held in stasis, on a journey to another world. Elsewhere, Nick Cave’s embellished soundsuits provide a shield – costumes that temporarily disguise the skin colour of whoever wears them, whilst not erasing their identity. “Cave constructs the soundsuits initially as a way to reckon with the ways the Black figure has been typecast and stereotyped in crude, animal ways in American culture,” Eshun continues. “The garments become a way to live and reclaim agency. The suit is a mode of armour.”

And yet, many of the artworks exist in a future that is closer to the present: where humans are rapidly changing alongside accelerating technologies. Dazed’s Editor-in-Chief Ibrahim Kamara (b. 1990) collaborated with South African photographer Kristin-Lee Moolman for i-D ‘ s 2018 Autumn Earthwise issue. Here, an androgynous Black model wears an elaborate technological mask which is split across the face, signalling the transformation of humans into cyborgs as the world hurtles into a virtual, robotic future. Similarly, the cover of Janelle Monaé’s 2018 album Dirty Computer invokes goddess-like symbolism as the singer stands in front of a flaming planet, wearing a beaded crystalline headdress, eyes downcast in devotion. The juxtaposition between the present moment and a fantastical world that transcends material reality is fundamental. “It’s a way of saying we, as Black people, can conjure ourselves – can think beyond the narrow ways that the white mainstream tends to see us,” Eshun notes.

The “Black Fantastic” is, truly, a category of its own making, borrowing from Afrofuturism and magical realism, whilst encompassing concepts from sci-fi, fantasy, speculative fiction, spirituality, myth, religion and metaphysics. The invisible and the intangible are key concepts: decentering the modes of western rationalism that stop spirituality and pre-Enlightenment belief systems from possessing any serious weight.

The works on show at Hayward reject the rational, clinical and “detached” objectivity of the white gaze. Just like the bird turning backwards to eat the egg – no matter how difficult, inconvenient or disruptive it is to break away from the continuity of the capitalist-modern present – In the Black Fantastic embraces the opulence and chromatic abundance of African traditions, which have evolved alongside the realities of enslavement, displacement, migration, rebellion and freedom.

“The search for political, personal and artistic liberation is one of the key components of the Black being and experience: the search within societies that are fairly intent in denying Black people their personhood in the west. That’s what I’ve lived with my entire life, and thinking about that in artistic terms, these are elements that recur time and again in the works of many different practitioners,” Eshun explains.

Liberation, after all, is not just a concept tied to wider topical themes in the show, or even the exploration or expression of Black identity: it’s also fundamentally an aesthetic. In Eshun’s essay, The Art of the Black Fantastic, which appears in the exhibition’s accompanying book, he writes: “Zora Neale Hurston defined ‘the will to adorn’ as a primary characteristic of African American expression. She could just as easily have been describing any number of forms of Black vernacular creativity, such as fashion, interior décor, quilting, dance or body adornment.” Aesthetic embellishment, a multiplicity of colours, profusion and excess – and the idea that more is more – permeate the show. The senses of exhibition-goers are provoked, scintillating a sensitivity to psychedelic colours, and intimating a creative pleasure that can best be in- spired by listening to an unfurling orally-transmitted mythic story, reading a brick-heavy sci-fi tome, or partaking in a Sunday church service with one’s entire voice and body. In the Black Fantastic centres spirituality and escapism, not as a reaction against the cyclical violence of institutional racism and the consequent psychological disassociation and alienation it causes, but rather as a new way of seeing the world and space in which Black people can reside free from the psychological brutality and power differential of racism, and of transcendence as a conduit for ontological liberation.

In the 1973 album cover of Sun Ra’s Astro Black, (also on show) a blue-purple light acts as a halo for the smiling jazz musician, the dusty glimmer of stars both on his figure and in the background. Ra claimed that he had a vision from aliens in outer space, and was teleported to Saturn. Whilst there, he was told to quit college and pursue music as a way of communicating with the world. He later founded the Sun Ra Arkestra, which continues to perform even after his death in 1993. Ra’s epiphany was not unlike visions that had visited other religious leaders, such as Elijah Muhammad (1897- 1975) of the Nation of Islam, John Africa (1931-1985) of the Philadelphia-based MOVE back-to-nature group, or Re- becca Cox Jackson’s (1795-1871) spiritual awakening, which led her to leave her husband and six children, and found an egalitarian community of Black women belonging to the Shaker sect, an offshoot of the Quakers, who practised gender equality, forbidding marriage and procreation.

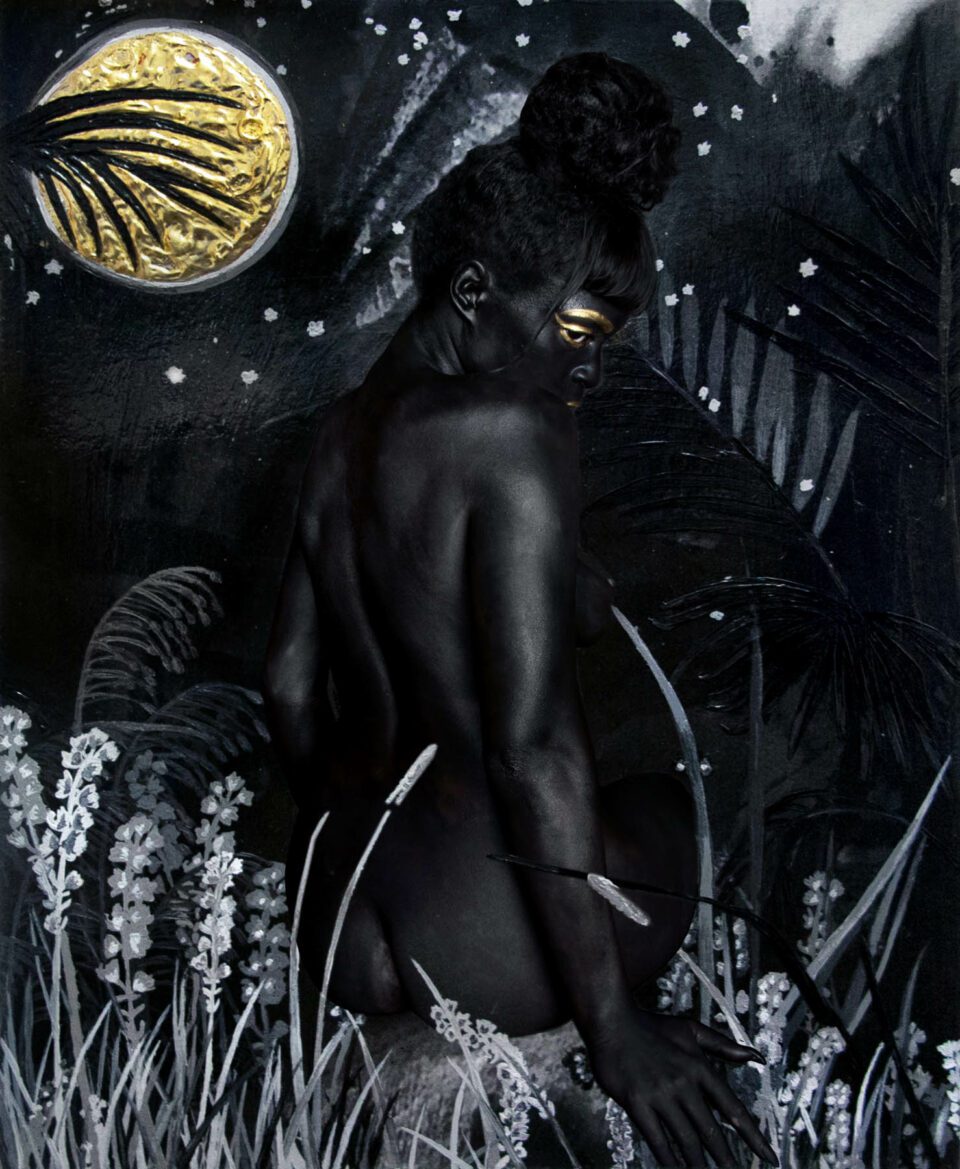

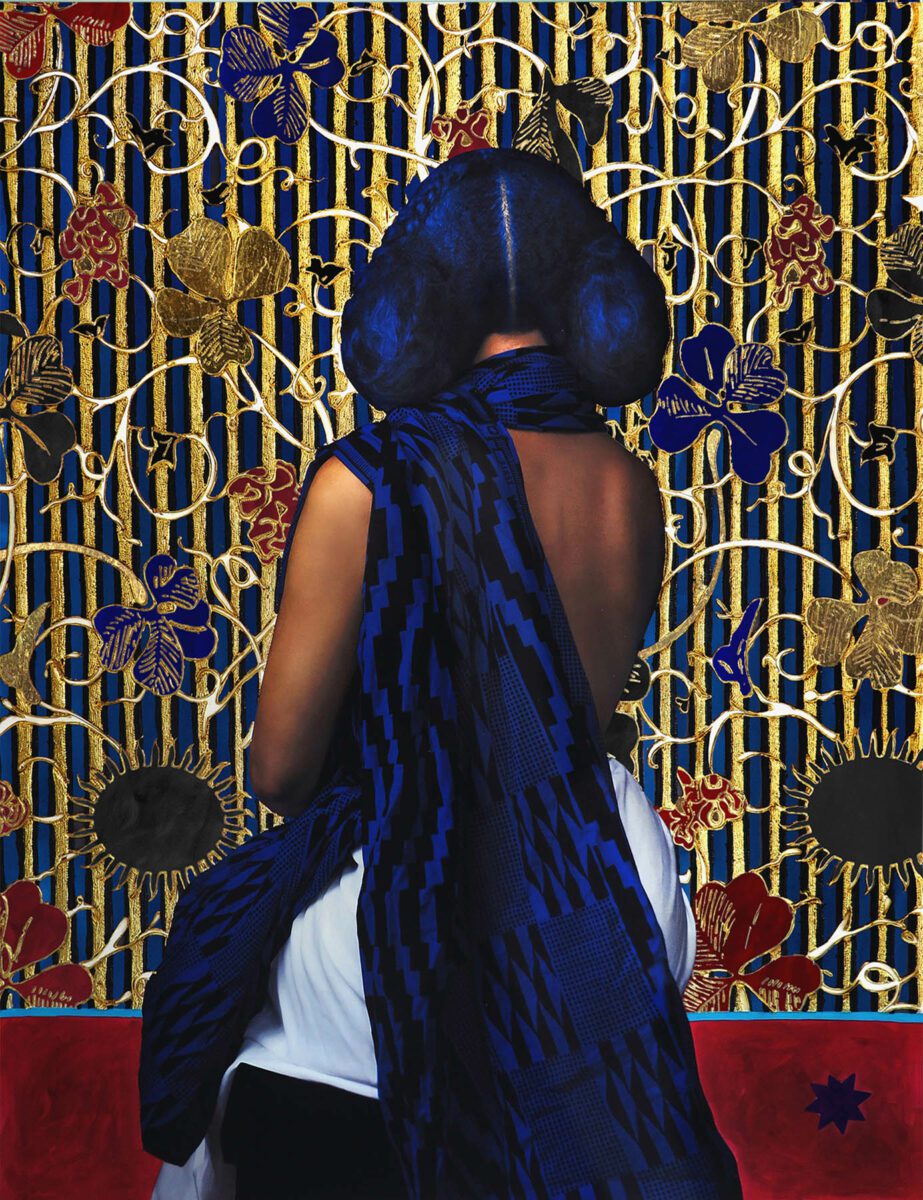

Lina Iris Viktor’s (b. 1987) A Haven. A Hell. A Dream Deferred series references the figure of The Libyan Sybil: a prophet from Greek mythology who could foresee the future. In continuity with the tradition of Black American women who have become seers, spiritual leaders and charismatic abolitionist activists, Viktor paints hauntingly beautiful portraits where breasts and faces are glazed over with saturated paint, whilst 24-karat gold inflects the background. The women in these layered, meticulous paintings are still, thoughtful and stoic, gazing past the viewer or outside the frame, as if witnessing a strange and horrible event, weighed down by the silent knowledge of a hushed, unspeakable happenstance. Has the event they’ve seen already occurred in the past, or is it a secret vision for the days to come? The answer isn’t clear, but the history that Viktor conveys is certainly of the past, even if it has repercussions in her parents’ native Liberia today.

“I wanted to have a conversation about the forgotten history that links Liberia to America,” Viktor notes. “Liberia is a nation founded by the American Colonization Society. It’s a reality that goes over many people’s head that [Liberia] is a sister- nation, and obviously, how this came about was not through altruism, but because of these uprisings in Haiti, and slavery being abolished in the North. All of these mixed-race former slaves, or children of former slaves, were considered to be too powerful and having too many rights, so it was a way to kill a fire before it started, repatriating people back to Africa.”

This repatriation led to an apartheid-like situation in which the indigenous population of Liberia was displaced to make way for the Black American settlers, and consequent upris- ings by the indigenous Africans were suppressed by the Americo-Liberians with the support of the US government. Cartographies span the backgrounds of Viktor’s paintings, tracing the geography of the land, and the gilded pain and violence shown in her series is ultimately intra-communal – a documentation of the tragic bloodshed that occurs when white supremacy and colonisation pit Black peoples against each other. “You always want to have this idea that there’s someone who’s a good guy, and someone who’s a bad guy in a scenario, and this shows the humanity [of people],” Viktor notes. “People that were once marginalised or once enslaved can become the oppressors as well. It’s a cautionary tale.”

Even so, uncomfortable conversations are at the heart of art and culture, as well as exhibition programming at the Hayward and beyond, pushing boundaries and provoking audiences to think in new and critical ways when we need to most. “Artists are meant to be these kind of conduits, these seers who move seamlessly through liminal spaces, bringing to the fore concepts that society is grappling with, or the underbelly of issues that are not being so widely discussed,” Viktor continues. “This is a way to traverse the bridges between our everyday lives – and imagine or believe what we could be. And to continue the mythology of imagining worlds and identities, of conjuring stories that take you out of the mundane and catapult you into metaphysical worlds.”

Words: Iman Sultan

In the Black Fantastic is at Hayward Gallery, London 29 June – 18 September

southbankcentre.co.uk | linaviktor.com

Image Credits:

1. Lina Iris Viktor, Sixth (2018). Pure 24 karat gold, acrylic, ink, gouache, copolymer resin, print on cotton rag paper, 52 x 40 inches (132.1 x 101.6 cm) © 2018. Courtesy the artist.

2. Lina Iris Viktor, Eleventh (2018). Pure 24 karat gold, acrylic, ink, copolymer resin, print on matte canvas 65 x 50 inches (165.1 x 127 cm) © 2018. Courtesy the artist.

3. Lina Iris Viktor, No. XXV We Once Sought Refuge There (2019). Pure 24 karat gold, acrylic, ink, print on cotton rag paper. 10 3/16 x 8 1/2 inches (21.6 x 25.9 cm) © 2019. Courtesy the artist.

4. Lina Iris Viktor, No. XIII Pause… Pause for A Paradise Lost Then Found (2017). Pure 24 karat gold, acrylic, ink, print on cotton rag paper. 10 3/16 x 8 1/2 inches (21.6 x 25.9 cm) © 2017. Courtesy the artist.

5. Lina Iris Viktor, First (2017-18). Pure 24 karat gold, acrylic, ink, gouache, copolymer resin, print on cotton rag paper. 52 x 40 inches (132.1 x 101.6 cm) © 2017-18. Courtesy the artist.