No Place Is an Island is the latest instalment in Photo50, London Art Fair’s annual exhibition series celebrating contemporary photography. The show responds to themes of ecology, migration and political nationalism through the work of 14 contemporary British photographers. Aesthetica spoke to the show’s curator Rodrigo Orrantia about collaborating with artists, working across media and unthinking the idea of islands. Originally scheduled for January, the fair is now postponed to 20-24 April.

A: Can you explain why the notion of the island attracted you when you were devising this show?

RO: I started thinking of this show during lockdown, after writing a piece on the absence of touch brought on by social distancing rules and enforced isolation. In the wake of Brexit, the climate emergency and now the ubiquitous Covid pandemic, what does it mean to be an ‘island?’ How do you define what an island is? This led me to research practices engaged with the idea of borders, of limits: both of the land but also of photography. I wanted to develop the idea of an island only existing as a mythical place, an imaginary construct. The topical issues of our time made it clear to me that there is no such thing as an island: the world is permeable and connected.

A: Can you talk about your typical process for working on an exhibition, including the way you interact and collaborate with artists, and how that worked in this case?

RO: I have been following the work of this group of artists for the last few years, and have worked with some of them on different projects. The exhibition process for me starts with finding connections between specific works or practices, then I get excited about bringing artists together around the same table. I don’t usually work just with just the pieces themselves—I want to get the artists involved, test my ideas with them. This is possibly one of my most ambitious experiments to date: working with 14 artists! I try to involve everyone in the decision-making process, from the selection of the works to the overarching narrative of the hang.

A: This exhibition is presented partly in homage to your mentor Sue Steward (1946-2017) and her Photo50 exhibition The New Alchemists (2012), which influenced you very much. Can you talk about that influence, and how you think art photography has developed since Sue’s show?

RO: I met Sue when she was working on The New Alchemists. As many people have said about Sue, she just had a contagious excitement about photography, and we instantly clicked. We must have spent hours in an empty pub up in Derby, me mostly listening. She opened my eyes – I dare to say everyone’s eyes – to a generation of artists working, as she put it, ‘beyond the print.’ The New Alchemists show was an absolute milestone for me, as was discovering Photo50 and a whole world of practices pushing the boundaries of the photographic medium. I think Sue’s show, and certainly the work of the artists in it, had a very noticeable impact on the way a certain type of photography has developed over the last ten years. Sue sadly passed away a few years ago, so this is partly a tribute to her and her work—she would have loved this project.

A: One idea behind the show is that photography is not an island: that it overlaps with other media. Can you talk about how the works on display get this across?

RO: That’s one of my favourite ideas of this show: photography is not an island. As a medium it can sometimes can get really rigid, really prescriptive. But it’s been very exciting to work with artists that investigate other worlds in order to enrich and enhance practices rooted in photography. My background as an art historian draws me to these territories of dialogue and experimentation. Artists like Tom Lovelace and Shepherd Manyika are interested in using their own body and presence as a sculptural object within their work. And then there’s Sarah Pickering’s seminal Explosions, a series of explosions captured on camera as sculptural objects. I could keep going with all of the other work in the show…

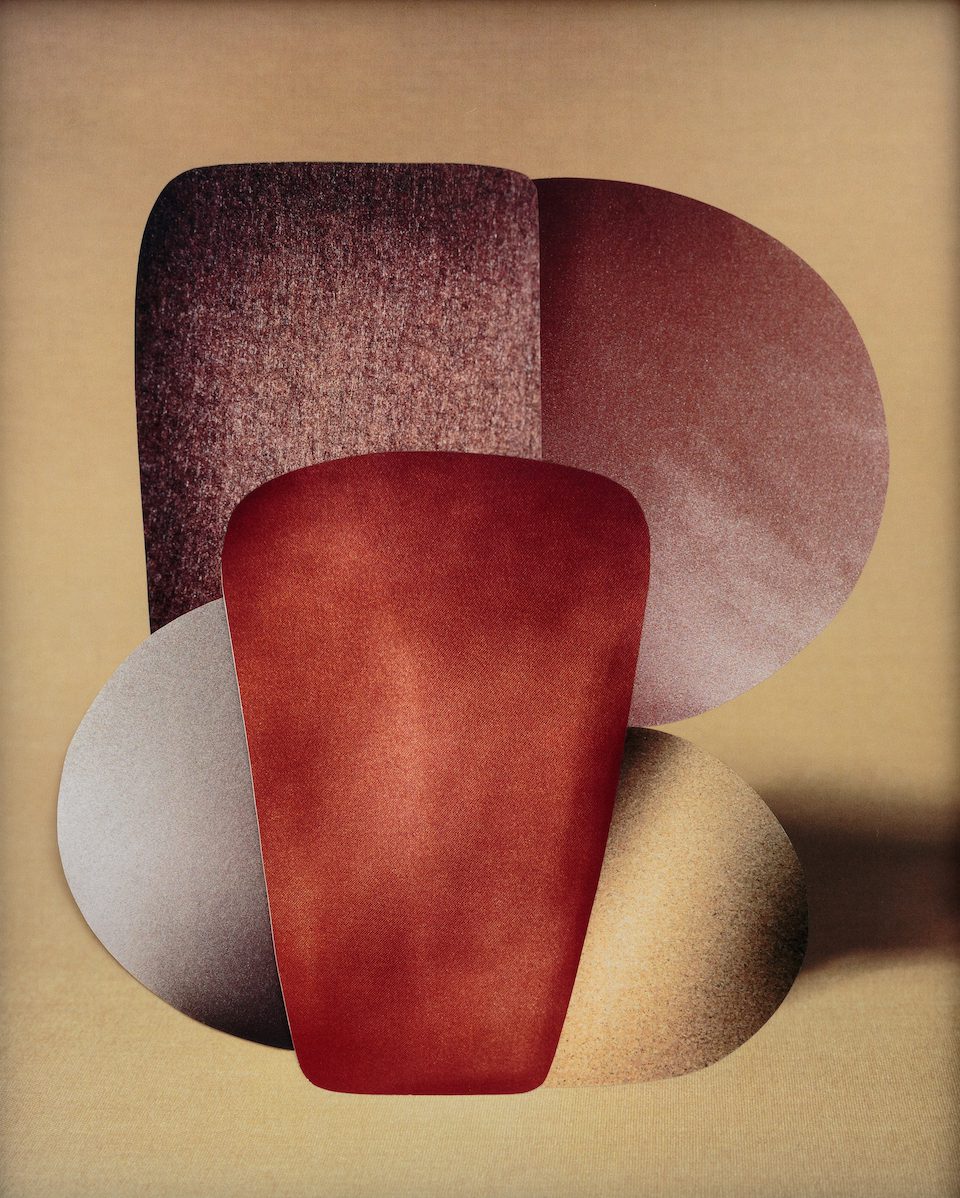

A: What about connections to sculpture and collage, for example, in the work of Dafna Talmor and Hannah Hughes?

RO: I have been following both Dafna’s and Hannah’s work for many years. They have very distinctive types of work, but I also knew there were multiple connections between their practices, especially through the idea of the sculptural in photography, and the use of collage techniques to ‘construct’ an image. I worked with Hannah on previous occasions to explore the idea of breaking the ‘bi-dimensionality’ of the photograph: how to bring the image into the three-dimensional world of the object. And I know this is something that Dafna is also interested in. So for this show I asked if they’d work on a piece together. It is going to be very exciting, and it resonates with the wider idea behind the show: no practice is an island, the contemporary world is all about connection and collaboration.

A: What about the connections between photography and film-based work, as in Alexander Mourant’s film piece A Vertigo Like Self (2019)?

RO: Photography and film share a common history: they are interlinked from birth. Analogue film is especially close to the photograph. I was instantly drawn to Alexander’s A Vertigo Like Self because it presented both the image and film substrate as equally important in creating the illusion of temporality, and the idea of a journey. We share a love for the object—you’ll be able to sense this from the prints that accompany Alexander’s film.

A: What does the work in this show suggest about the future of photography as art?

RO: I am very curious to see the reaction of someone coming to the show to see ‘photographs,’ which is what you expect from the big photography fairs across the world. In the realm of art there are different rules: although it’s a complex and demanding world, it is also much more open to new ideas and experimentation. I think this show is very important. My hope is to see an expanded version of it in an art museum—it should open up needed conversations about the future of photography as art. These works gain a lot when seen in context, and it would be great to be able to keep them together. As an art historian I constantly think of how works like these will be read and understood in 50 or 100 years—they gain a special weight and timelessness when you think about them in that light. For me they are very representative of the moment we live in.

No Place Is an Island runs at London Art Fair 20-24 April. Find out more here.

Words: Greg Thomas

Image Credits

1. Dafna Talmor, From the Constructed Landscapes II Series, 2019

2. John MacLean, Hometown of Bridget Riley, Padstow, Cornwall, 2017, Courtesy of Flowers Gallery

3. Hannah Hughes, Tuck, 2020, Image Courtesy of the Artist

4. Sarah Pickering, Landmine, 2005, Courtesy of the Artist