In April 1970, Museum of Modern Art, New York, opened a landmark show. Titled Photography into Sculpture, it was marketed as “the first comprehensive survey of photographically formed images used in a sculptural or fully dimensional manner.” The exhibition featured more than 50 artworks, including Robert Heinecken’s (1931-2006) illusionist film and plexiglass puzzles, and three-dimensional landscape prints by Ellen Brooks (b. 1946). The Curator, Peter C. Bunnell, defined these multidisciplinary pieces as “beyond those of the traditional print, or what may be termed ‘flat’ work.”

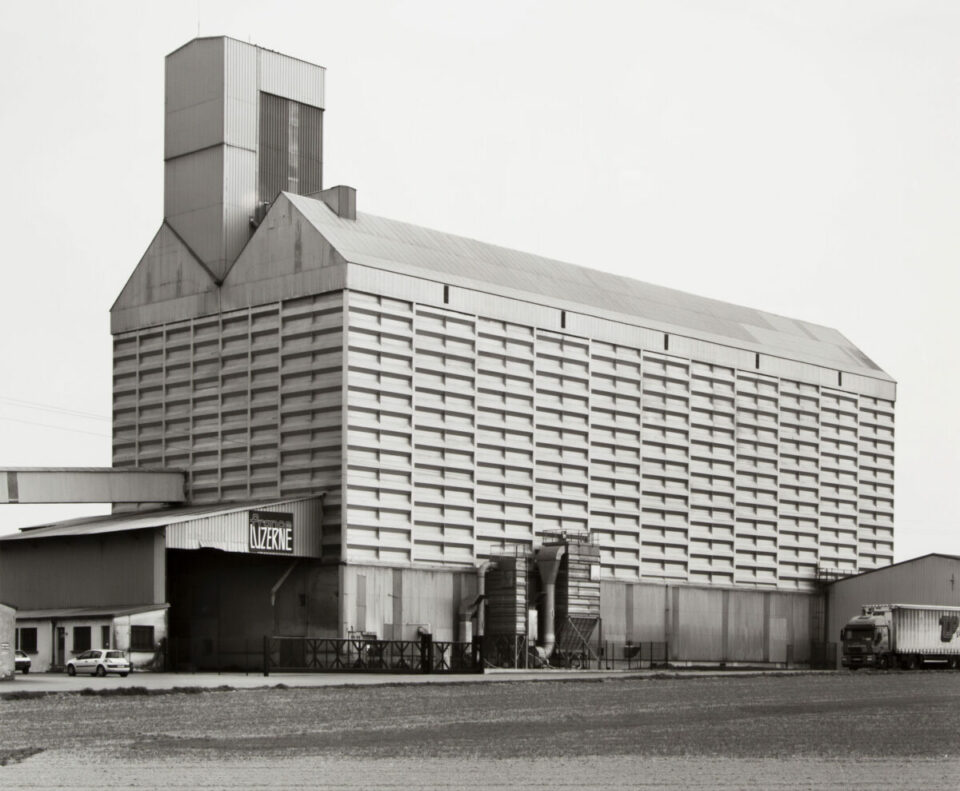

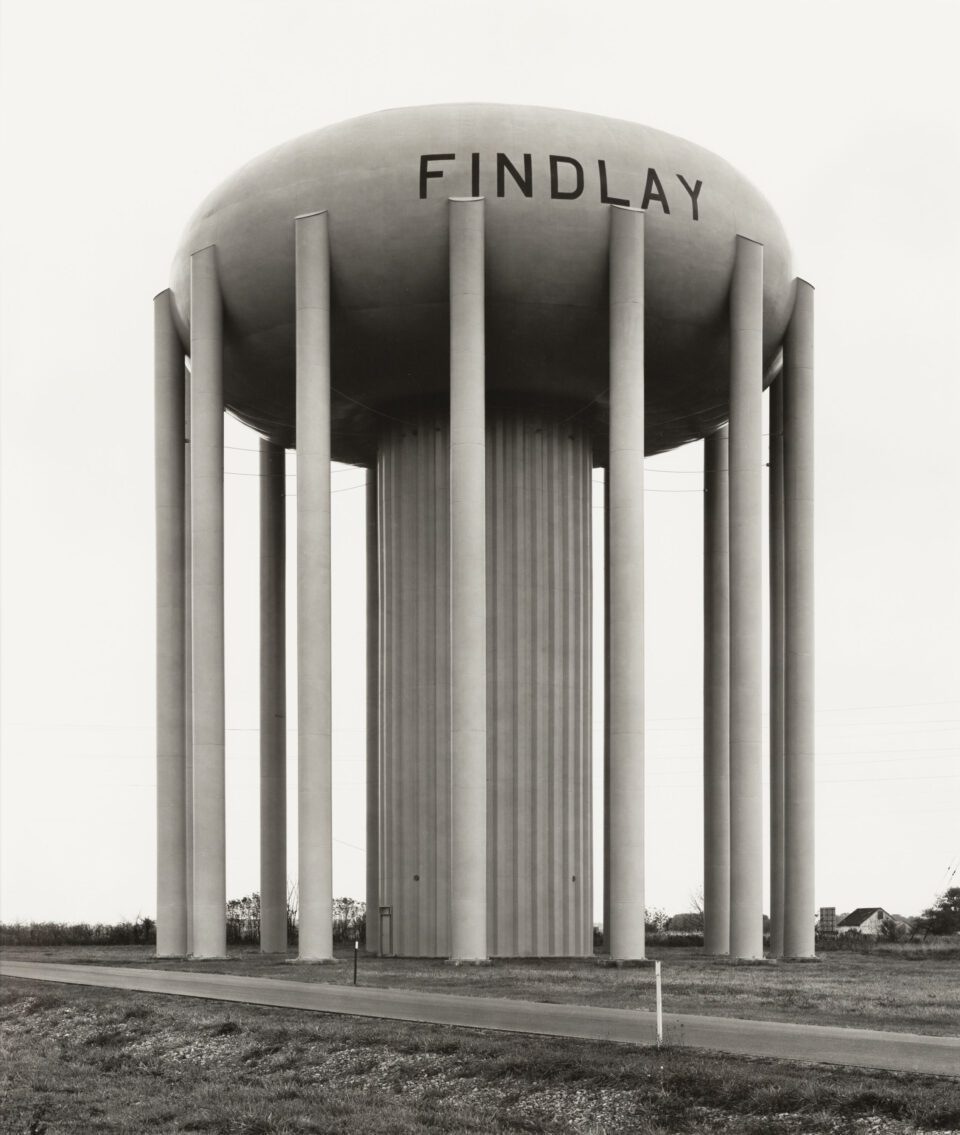

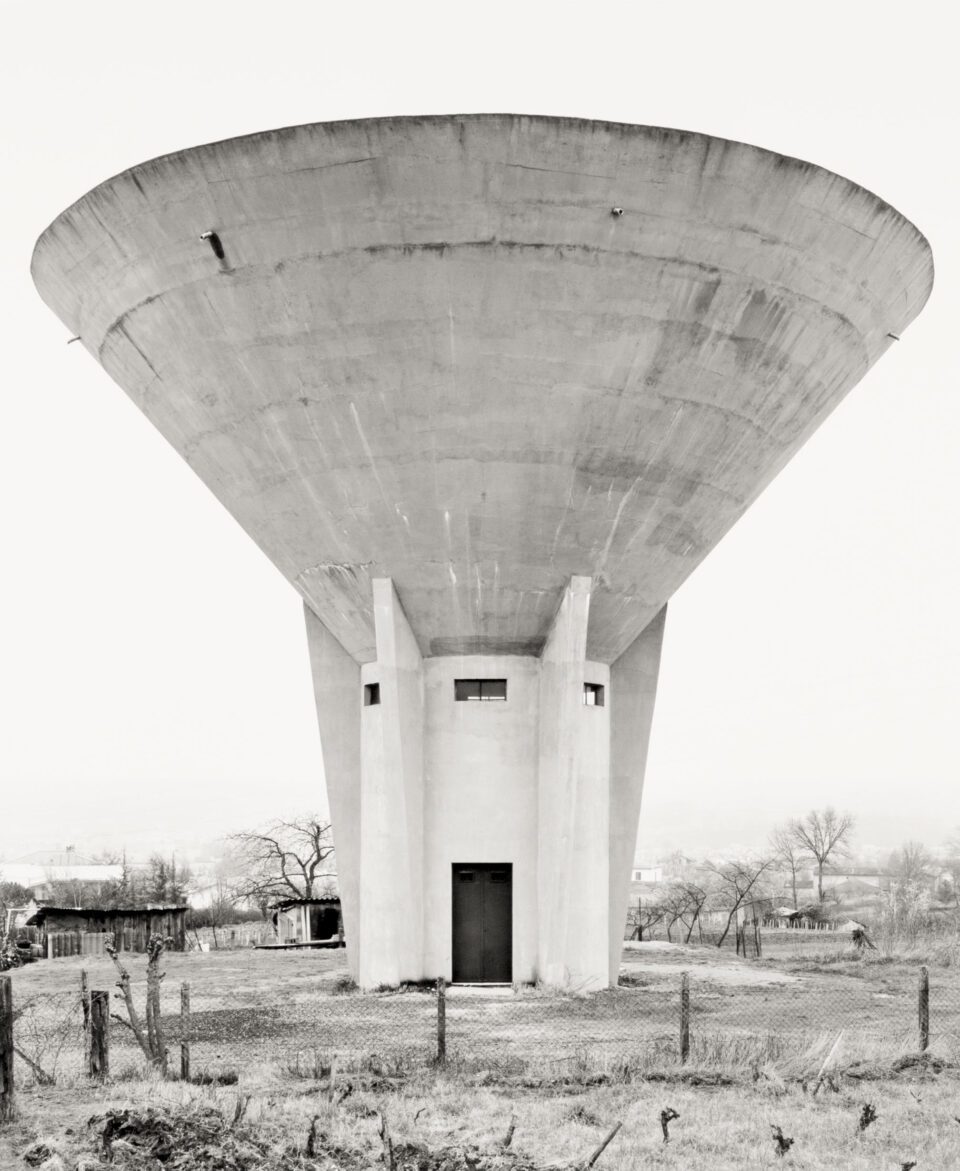

This approach – where image-making and 3D design meet – gained significant traction in the latter half of the 20th century, with pioneering creatives like Barbara Kasten (b. 1936) breaking the mould. Influential German artists Bernd Becher (1931-2007) and Hilla Becher (1934-2015) were also at the forefront, documenting now-demolished industrial structures across Europe and the United States. Cooling towers, kilns, blast furnaces and grain elevators are recorded in a signature uniform style: monochrome, grid-like, objective. Notably, the Bechers did not always refer to their work as photographs, instead labelling them as “anonymous sculptures” – a title given to their 1970 photobook. The duo received a Golden Lion for sculpture at the Venice Biennale in 1990; the accolade was given for their contribution to historic preservation, recognising the intersections between seemingly disparate fields.

Now, San Francisco’s Fraenkel Gallery launches a retrospective spanning five decades. The survey focuses on the Becher’s precise and repetitive cataloguing of disappearing architecture. Images appear frozen in time, immortalising monumental relics of 20th century industrial production. “They are simultaneously witnesses and redeemers of an aspect of our times that is destined to vanish,” states Weston Naef (b. 1942), former Curator of Photography at The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

The Bechers’ systematic approach resembles that of scientific inquiry – utilising grid formations to create detailed inventories. Photosets are exhibited in rows and columns; typologies such as Water Tower, for example, arrange six shots recorded between 1963 and 1972. It’s an organisation strategy which allows for detailed observation, such that viewers can pinpoint similarities and differences in visual characteristics. “Through photography, we try to arrange these shapes and render them comparable,” Hilla Becher once said. “To do so, the objects must be isolated from their context and freed from all association.” As a result, circular blast furnaces loom over viewers, and water towers teeter on the edge of the printed page.

In 2023, the boundaries between art, science and technology are more slippery than ever before. In fact, the Bechers have had a profound influence on this transition, with some of the great technological and architectural photographers of our times – Andreas Gursky, Candida Höfer and Thomas Struth – taught by the duo at Kunstakademie Düsseldorf. Most recently, AI generators have been making headlines for producing everything from selfies to visions of our architectural future. Looking back at these works today shows us how far we have come, and begs the question: what happens next?

Fraenkel Gallery | fraenkelgallery.com

Until 25 February

Words: Megan Jones & Eleanor Sutherland

Image Credits:

1. BERND & HILLA BECHER, Grain Elevator, Coolus, Châlons-en-Champagne, France, 2006. gelatin silver print. © Estate Bernd & Hilla Becher, represented by Max Becher. Courtesy Fraenkel Gallery, San Francisco.

2. BERND & HILLA BECHER, Water Tower, Findlay, Ohio, USA, 1977. gelatin silver print. © Estate Bernd & Hilla Becher, represented by Max Becher. Courtesy Fraenkel Gallery, San Francisco.

3. BERND & HILLA BECHER, Water Tower, Carmaux, France, 1984. gelatin silver print. © Estate Bernd & Hilla Becher, represented by Max Becher. Courtesy Fraenkel Gallery, San Francisco.