The Scottish photographer Iain Stewart (b.1967) first became known as a portraitist and documenter of social realities during the 1990s. As the curator and critic Trudy Wilner Stack writes in her afterword to his new book, Inner Sound: “he can tell people’s stories in an unfolding series of photographs or in a single frame.” Arresting shots of novelist Alasdair Gray, and of a strike for the National Health Service in Edinburgh, are amongst a collection of his images from this period held by the National Galleries of Scotland.

This volume, published by Another Place Press, takes Stewart far from the human worlds which preoccupied him in his early work, juxtaposing images of land and sea with fragments of collaged text to draw out the relationship between place, perception and identity. For the last few years, Stewart’s attention has been occupied by landscapes, particularly coastal ones. As Wilner Stack puts it: “when Stewart took a mature turn as an artist, it was to where human face and form were not: he fixed his attention on the distant sea and its junction with the sky.” Stewart is especially preoccupied by the mountains and littoral fringes of the Scottish Highlands, including, in this case, the almost too-poetically named Inner Sound: the stretch of water that separates the Inner and Outer Hebrides.

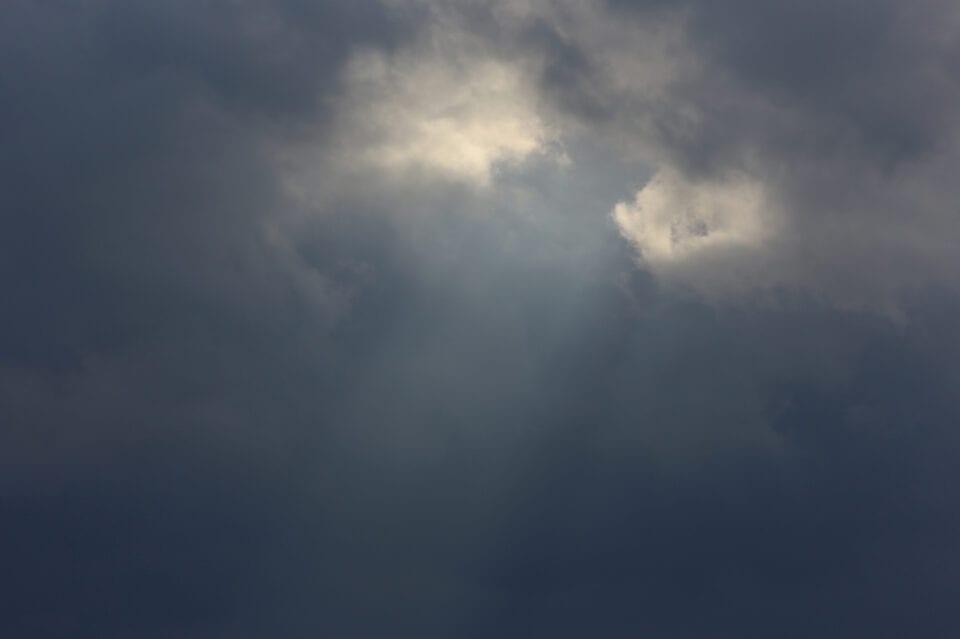

His latest publication traces a journey from snow-covered hinterland – where tiny black flecks of foliage, fencing and rock scree cut through a softly encompassing whiteness – to bright blue skies with strange downward strokes of cloud, to grass-strewn approaches to the shore. The images avoid the kind of detail that would anchor them in a particular location: compositions are made up of a few, intersecting diagonal, horizontal or vertical elements, so that they come almost to seem like the form of the thing (the sea, the sky, the hills) rather than any particular instance of it.

The occasional gatherings of language that accompany the photographs – from Latin words to borrowed poetry from Virgil and Seamus Heaney – offer a kind of unobtrusive curation, providing context for the images. The heavenly connotations of the clouds are signified by the word “Celeste”, for example, and the sound made by crashing waves is implied by the term “Sonogram”, printed on the facing page. Like the abstract paintings of Mark Rothko – a point of comparison offered in Wilner Stack’s afterword – these elementary compositions in colour and shape become documents of a universal human drama, representing elation, suffering, healing.

The images also serve as a kind of photo-diary for Stewart. In his introductory note, The Last Man on the Mountain, the artist recalls a moment of sudden recollection on approaching the beach which – we assume – is presented across the following pages: “decades earlier, in another century, I’d raced through summer wildflowers and cotton-grass to those same sands with my parents – losing a shoe, sticking in the peat bog – but here I was 40 years later, alone, in a different season, travelling North, not South, seeing it from reverse.” The act of recollection is sharpened by what already know: that Stewart is returning to the beach a year after his father’s death (from Alzheimers, as is later revealed). The images not only attempt a kind of universality – whatever that might mean – but are also inscribed with a language of individual mourning.

This personalisation of the landscape also reminds us that the Scottish Highlands have not always served as a blank canvas for the romantic imagination. At one time they were home to generations of crofters and farmers, most of whom were removed during the Highland Clearances. Another page of images is pointedly accompanied by the term “erasure.” Not merely an evocation of sublime wilderness then, but a collection of images at once more personal and political. As the nature writer Robert MacFarlane notes of this collection: “there’s something original and ambitious at work here; a shard-like hard-cutting between image and place and text.” Inner Sound is both a paean to place and a document of the subjective and social forces always bound up in our perceptions of the natural world.

Inner Sound is published by Another Place Press. Find out more here.

Words: Greg Thomas

All images by Iain Stewart, from Inner Sound. © 2020 Iain Stewart and Another Place Press