The first partially successful camera image was made in approximately 1816 by French inventor Nicéphore Niépce. After Niépce’s death in 1833, his partner Louis Daguerre continued to experiment, and by 1837 had created the first practical process – the daguerreotype – which was publicly unveiled in 1839. In 1840, across the English Channel, the Wiltshire-based polymath Henry Fox Talbot perfected a different process – the calotype.

The invention of the camera gave birth to a mass media tool. In the 180 years that have followed, photography has become the most rolling communication of our opinions, lives and contemporary society. The visual language of documentation, surveillance, expression and communication is constantly being renewed. With the launch of Apple’s iPhone 11 in mid-September – with an advertised dual-camera system and a new ultra-wide lens – image-making has never been so easy, or so utterly possible. It is time, once again, for us to re-assess what visual media can be, and how we define its legacy. So what makes a photograph a photograph? What distinguishes fine art from data? What’s the difference between flicking through a book of rare prints and scrolling through Instagram?

Rifling through Viewpoints: Photographs from the Howard Greenberg Collection provides some kind of answer. Since opening over 30 years ago, Howard Greenberg Gallery, New York, has built a vast and ever-changing collection of powerful and meaningful images that come together to present a collective memory – spanning continents and decades. It now totals 446 pieces by 191 artists, acting as a living history of the medium. It includes a plethora of household names from the 20th century, including Gordon Parks, William Klein, Berenice Abbott, Walker Evans, Diane Arbus, Ed van der Elksen and Bruce Davidson. In doing so, the text – and accompanying exhibition at Museum of Fine Arts Boston – demonstrates how each of these names have contributed something individual and unprecedented in the journey of photography. Each of them have created something integral to the developments of image-making, using analogue as a stepping stone of experimentation.

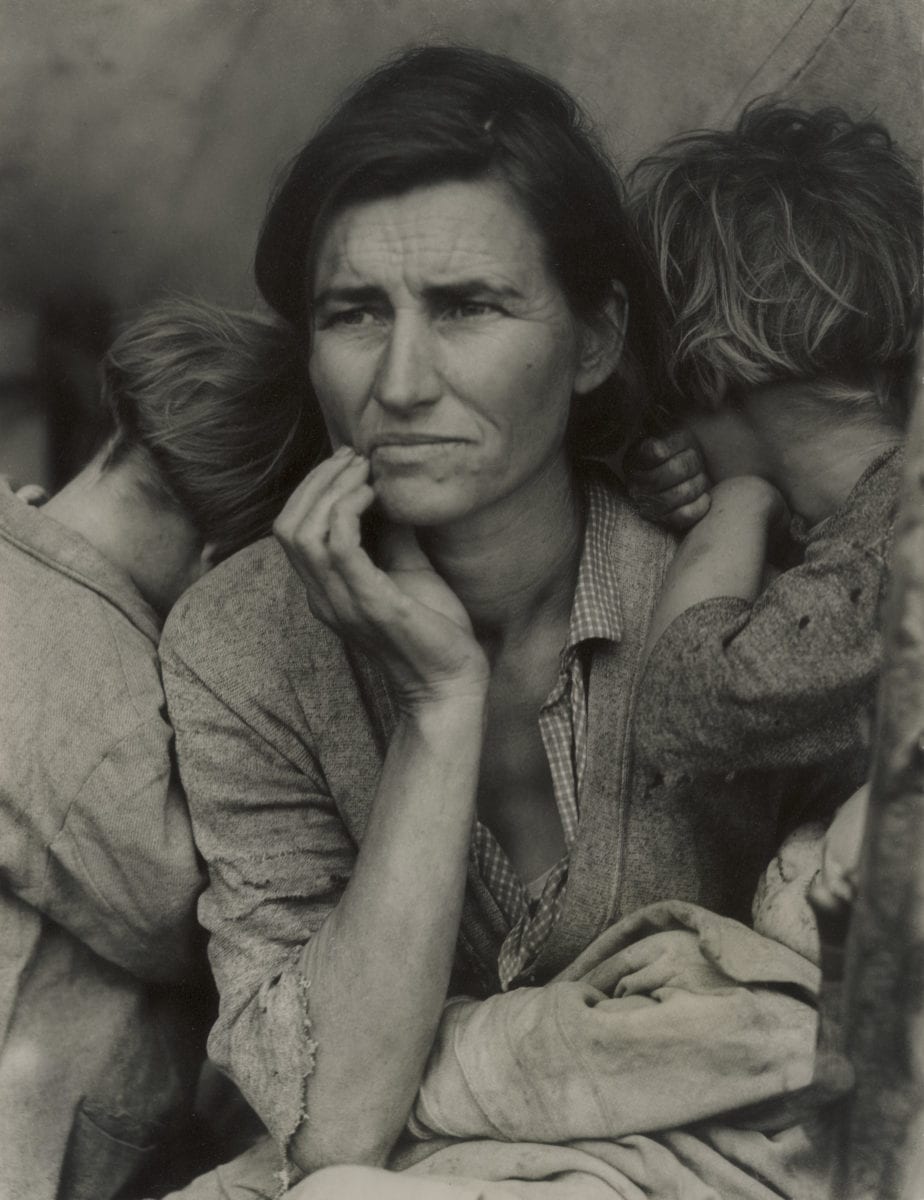

The featured works include “secular icons” that have permeated visual history again and again. Notable examples include Dorothea Lange’s Migrant Mother, Nipomo, California, 1936. It was taken whilst Lange was employed by the US government’s Farm Security Administration (FSA), formed during the Great Depression to raise awareness and provide aid. Lange’s image captures Florence Owens Thompson and her children – a family devastated by the failure of the pea crops. Presenting the true human cost of the Depression, it has become one of the most iconic pieces of the period.

Perhaps a lesser-known – but equally powerful – example is Consuelo Kanaga’s Young Girl in Profile, 1948. With a masterful use of lighting, the portrait demonstrates an immense amount of depth and contrast. The girl, who remains anonymous, gazes upwards: solemnly, peacefully. The effect is compelling; onlookers are left trying to discern the emotions at play and the thoughts behind the eyes. Kanaga often photographed strangers – mostly from African American communities – with compassion and empathy. Kanaga believed that image-making – unlike today’s fast-paced point and shoot portraiture – should be a longer process built upon trust between the subject and the artist. In doing so, the viewer becomes part of a wider conversation about the human condition – about the ethics of gaze and the inherent responsibility we all have when viewing and interpreting visual information.

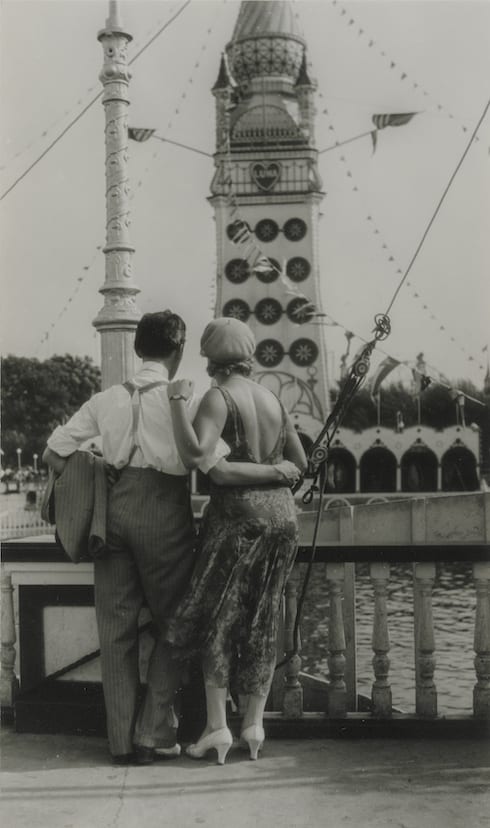

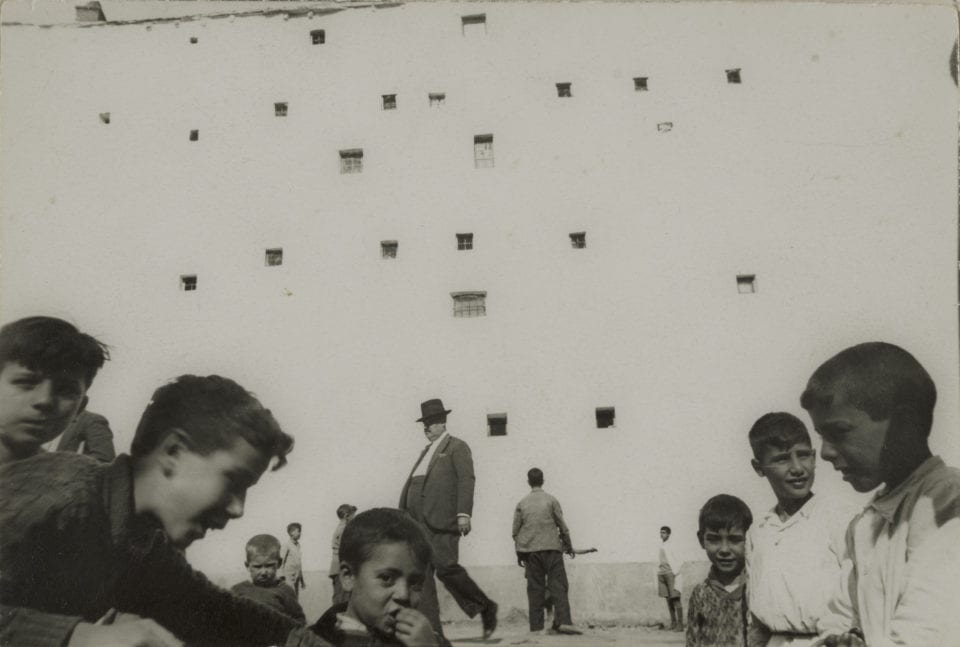

Moving into street photography, Henri Cartier-Bresson and Walker Evans offer groundbreaking perspectives. In Madrid, Spain, 1932, Cartier-Bresson depicts children at play in an open square, soft sunlight falling on their open faces. Evans’ Couple at Coney Island, 1928, is a less spontaneous example. A man and woman hold each other by the waist, staring into the river. So much is expressed in the semantics – leisure, intimacy, warmth.

Other notable works in the collection include André Kertész’s Chez Mondrian, Paris, 1926 – a beautifully composed view into a home. A staircase descends through a doorframe. A plant rests silently on the table. Light falls through the room casting shadows across a table. Edward Steichen’s Three Pears and An Apple, France, 1921, is equally interesting texturally – with light and dark rendered almost like brushstrokes. Of course, the collection also depicts some of the more harrowing events of the century, including Robert Capa’s documentation of the D-Day landings in Normandy and Eddie Adams’ taut and heart-rending capture of a Vietcong fighter being executed by the national police chief of South Vietnam, 1968.

Together, this book is a guide to “secular icons” – important images that have permeated the visual world and constructed our notion of recent history again and again. As Kristen Gresh, Senior Curator of Photographs at Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, notes: “Embodying all of the transformative qualities of the medium, the selected works represent an art form as well as a social, cultural, and political force. They capture different emotional realities and serve as a window into the 20th century, confirming photography’s ability to transport the viewer to other times and places.”

Beyond the visual, there’s historical importance in the material properties of the prints. Many of the works in the collection are the first or only print of the image, or the best existing example. Whilst digital platforms like Instagram are almost unparalleled in their capabilities for sharing and disseminating ideas, the prints in Viewpoints provoke the reader to ask inherent questions about value and antiquity. We live in an age where everything can be replicated in seconds. Mass-consumption and product reinvention is taking place at such a rate that electronic items are being shipped across the world and burnt in huge, desolate wastelands.

These works endure – beyond analogue nostalgia or the documentation of important historical moments – because they offer a sense of authenticity. They cannot truly be replicated, and they exist to be seen in printed format, or on the gallery walls. They’re not made for two-dimensional RGB screens. This book, and accompanying exhibition, reflects upon the notion that the past should be treasured, recognising the unique contributions of the 20thcentury’s most notable practitioners. As Gresh notes: “Absorbing and responding to today’s infinite supply of images requires a new level of filtering and a radically different kind of visual literacy. Today, photographs are reproduced digitally and viewed on screens of all sizes; they are seldom printed. Their capacity to be remembered has been diminished by the fact that they rarely exist as lasting, physical objects. The black-and-white works in this book are bound together by the distinguishing physical qualities of the prints themselves, and their ability to create a transformative experience.”

Viewpoints: Photographs from the Howard Greenberg Collection is published by MFA Publications. The accompanying exhibition is on view at Museum of Fine Arts Boston, until 5 December. For more information, click here.

Kate Simpson

Credits:

1. Young girl in profile, Consuelo Kanaga (American, 1894–1978) 1948. Courtesy, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

2. The Daughter of the Dancers (La hija de los danzantes), Manuel Alvarez Bravo (Mexican, 1902–2002) 1933. Photograph, gelatin silver print. Courtesy, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

3. Migrant Mother, Nipomo, California, Dorothea Lange (American, 1895–1965) 1936. Courtesy, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

4. Madrid, Spain, Henri Cartier‑Bresson (French, 1908–2004) 1933. Courtesy, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

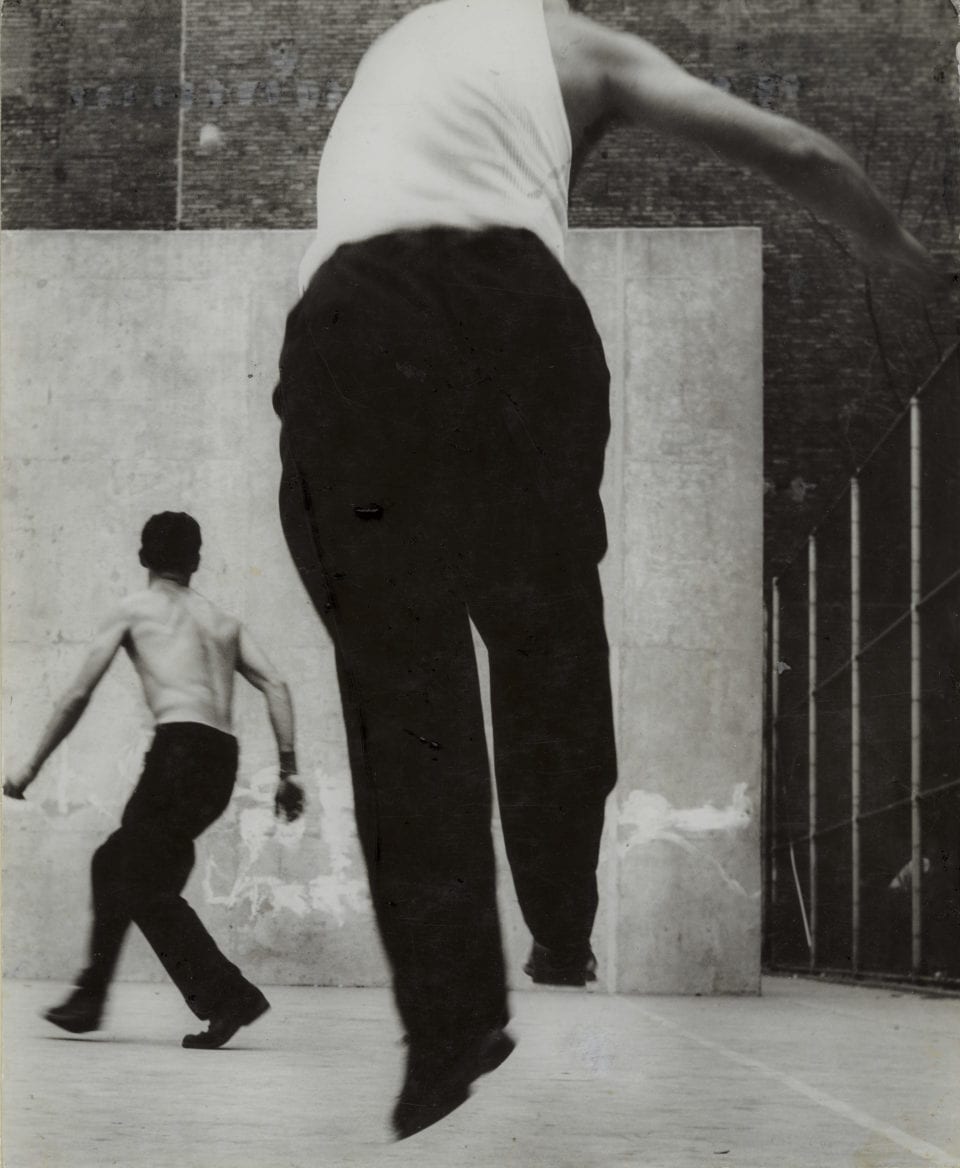

5. Handball Players, Houston Street, New York, Leon Levinstein (American, 1913–1988) 1955. Courtesy Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

6. Couple at Coney Island, Walker Evans (American, 1903–1975) 1928. Courtesy, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.