In 2019, photojournalist Lorenzo Tugnoli was on assignment in Afghanistan. He’d lived in the country between 2009 and 2015, before returning with The Washington Post during a period of political upheaval. The USA and Taliban signed an “agreement for bringing peace to Afghanistan” in February 2020, after 18 years of conflict and the period that followed saw the complete withdrawal of foreign forces, the collapse of the Afghan Republic and, in August 2021, the Taliban’s full return to power. Tugnoli’s new book, It Can Never Be The Same, documents this pivotal time of transition, turning the lens on the ordinary lives shaped by international events. The publication goes beyond traditional reportage, asking how visual representations can shape external perceptions of a nation. Each photograph is cinematic, with dramatic light and shadow, depicting both sweeping landscapes and everyday details, moments of intense conflict interspersed with domesticity. Tugnoli spoke to Aesthetica about the process of creating the book, the responsibility of photojournalists and why we should be asking questions about the distance between who gets to tell the story and those who actually live it.

A: Take us back to the beginning. How did this project begin?

LT: The images were taken in Afghanistan between 2019 and 2023. Most of them were shot on assignment for The Washington Post, and later I worked independently to fill in the narrative gaps I felt were missing. The process of turning a series of images that were initially made for a newspaper –focused on the narrative of several news stories – into a book can be tricky, and it doesn’t always work. Work produced for a newspaper can often be fragmented, so I needed to supplement it with additional material. There were a few factors that helped smooth this out. First, I had already spent a long time in Afghanistan as I lived there between 2009 and 2015. Second, by 2019 my relationship with the paper was strong and I had more leeway to decide which projects to take on. I was also aware of my intention to build a coherent body of work early in the process. In the book, I intentionally acknowledge many of the people “behind the lens,” who were essential in making my work on the ground possible. The opening quote is from Asad Haidarzai, the longtime Kabul driver for The Washington Post, who has taken generations of correspondents around the country. One of the last images in the book features Aziz Ahmad Tassal, an Afghan journalist who worked with us and translated everything we saw and experienced during those last years.

A: Rather than traditional reportage, the collection of images in the book forms a reflective journey. Why did you choose this creative approach?

LT: To edit the book, I decided to go back and review all the raw material I shot over those intense five years in Afghanistan. I did this because there’s a real difference between images that work in a newspaper and those that work in a book. The process took more than a year and became a deeply intense moment of reflection on my practice and what I wanted to do in the future. This wouldn’t have been possible without the collaboration of Francesca Recchia, a writer and scholar who led the conceptual direction. We were acutely aware of the pressure of creating a meaningful book about Afghanistan. It’s a place that appeared in newspapers and photobooks long before I was born and featured in the work of many masters of photography, from James Nachtwey to Steve McCurry, from Simon Norfolk to Jeff Wall. So I asked myself: what is my position in all this? In terms of my role within the history of photography, but also my position in relation to what I can and cannot say about a place I wasn’t born into – even if I spent more than a decade covering it. In search of artistic honesty, I decided to shift the focus of the book away from the idea of “telling the truth” about Afghanistan – an approach often employed in traditional photojournalism – toward acknowledging what I was actually doing there: building a representation of the country for a foreign audience. Ultimately, the book explores how we construct representations of a place.

A: How do you see the camera as a tool for representation?

LT: The lens produces fiction and interpretation – it’s important for a photojournalist to be aware of that. In the best-case scenario, what we produce is a story that comes as close as possible to what we believe is the “truth” (and, of course, we can debate the meaning of that word). From this, we can build intentionality around the visual grammar we use and the clichés we choose to include or omit. Images exist within a history of what has been represented before and how it has been done. As international photographers, we interact with a tradition – and sometimes with misrepresentation – and although it’s not always possible to push the discourse forward, it is crucial to work with this understanding.

A: Why did you choose to shoot in black and white?

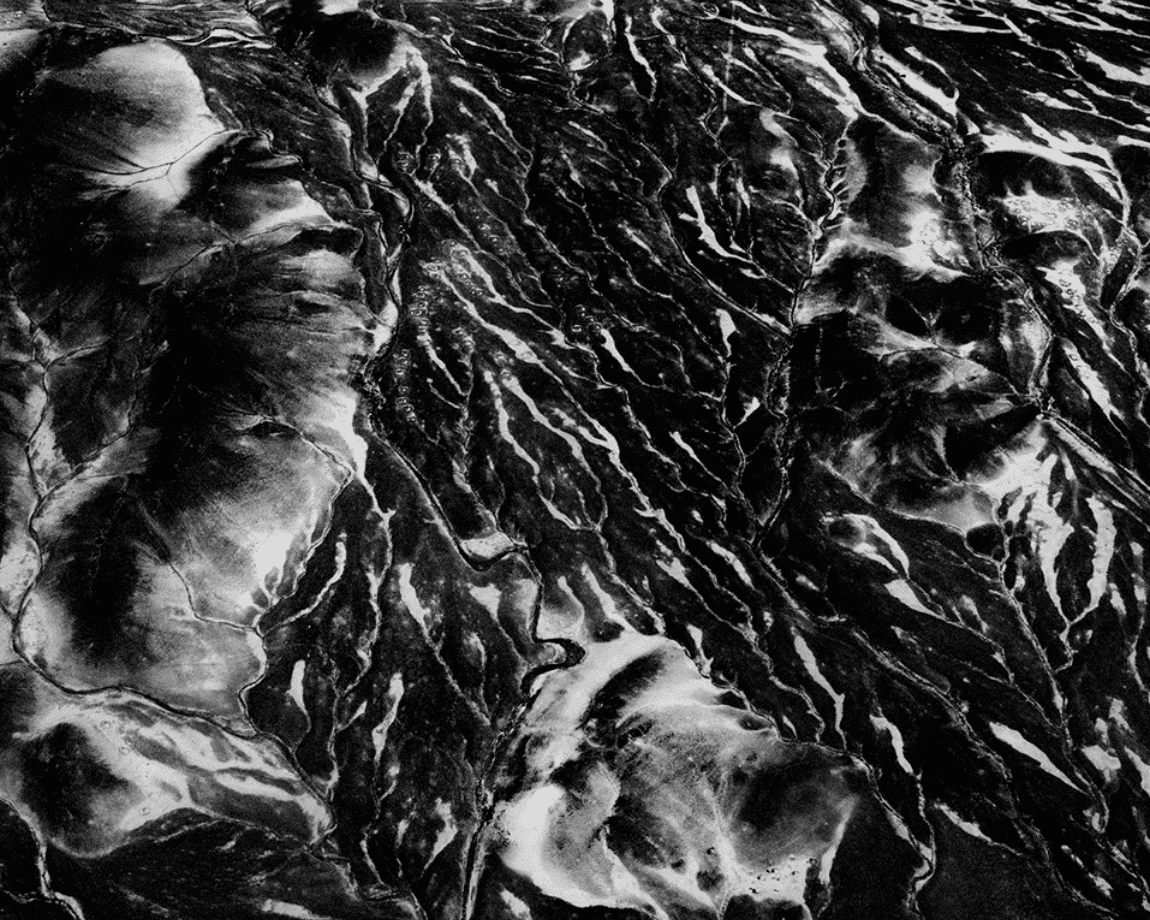

LT: There are various factors that led me to choose black and white. It was initially a decision inspired by a certain kind of photojournalism that I admired early in my career. The late 1990s and early 2000s were the peak years of the print industry, and black-and-white reportage was still very much in vogue. Black and white evokes the past and carried its own allure, tied to presumed journalistic authority and its association with slower, more in-depth work. It stood in contrast to fast-paced, color news photography that is produced, published and forgotten within hours. Of course, my vision has evolved since that first infatuation. The way this visual language is employed in the book ultimately questions it rather than celebrates it. It doesn’t offer truths or accusations, but instead constructs a world that tells the story of war in all its ambiguity, reflecting the experience of working as a journalist in a country that resists linear readings. Afghanistan has long been at the centre of a mission with an uncertain meaning: it began as a reaction to the 9/11 attacks and continued for 20 years under the promise of bringing human rights and development. It is a narrative that proved entirely false when NATO and the USA abandoned the country overnight, leaving Afghans once again under Taliban rule and cutting nearly all humanitarian aid. In the book, this traditional visual language of photojournalism – usually associated with the “witness” and the document – makes space for ambiguity and the many layers of meaning journalists encounter on the ground. That space of ambiguity is also what fascinates me most about photography.

A: You intentionally sought out sequences that lacked a singular narrative, and you only placed captions at the very end of the book. How does this uncertainty reflect the situation in Afghanistan?

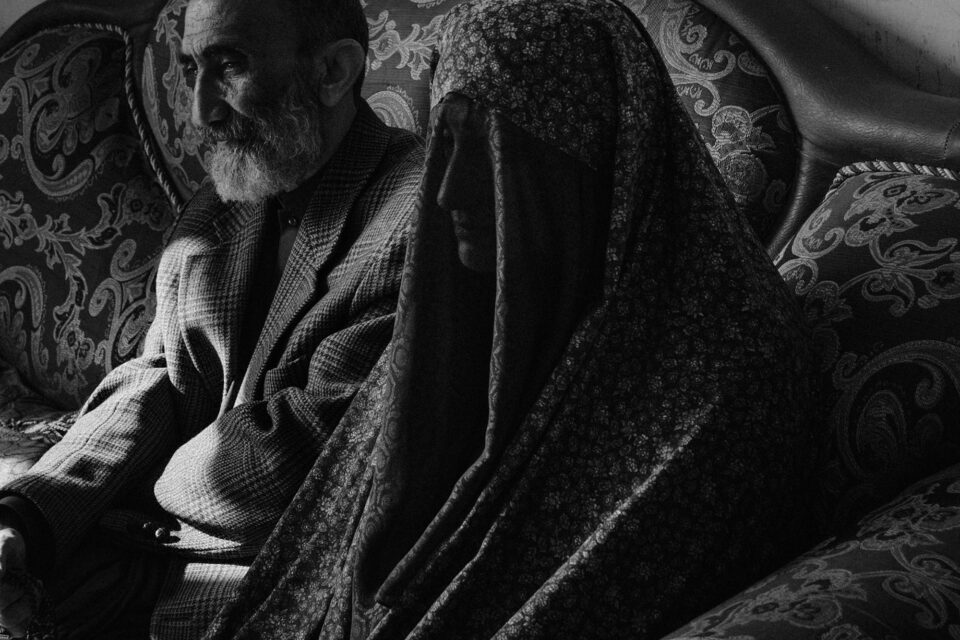

LT: I want to take the viewer into a world where they won’t necessarily understand what’s happening right away, but may feel curious to learn more. If they want, they can find out more by reading the captions at the end. The idea is that Afghanistan is a country with thousands of years of culture and history and a deeply layered identity. I don’t want to interpret it for the viewer – I want to speak about this complexity. I want to say that, often, things are not what they seem at first glance. The book also includes many references to cinema, from the landscape format of Cinemascope, to the lighting to the grids. I used these ideas to reflect on the work of the photojournalist, who is often pushed to make “strong” images (a definition that could be discussed at length), rather than to truly engage with a place. Sometimes, we end up going to a place to make the film we already have in our heads, instead of trying to understand what’s in front of us.

A: You often capture quiet moments amidst chaos. What draws you to the everyday, and what does it reveal that conflict photography alone cannot?

LT: The focus on dramatic moments in war photography serves a specific function: it highlights a particular aspect of the story. But there is much more that goes on in a war zone. Most of what happens is everyday life, with moments of violent explosion interspersed within it. Showing the actual conflict can be important in some cases. For example, in the last phase of the war in Afghanistan, I felt the need to show the frontline because the struggle of the Afghan security forces was no longer widely represented in the media. The US Army had transitioned most ground operations to the Afghan forces and eventually stopped providing air support. With fewer US troops on the ground – and fewer American casualties – came a corresponding decline in media interest in visualising the conflict. But I was always aware that this is only part of the story. Much of it unfolds in the years before and after the dramatic moments of combat, when the soldiers have left and civilians are left to deal with the consequences of a senseless war for the rest of their lives.

A: You address the disconnect that foreign armies, media outlets and nations have when viewing life on the ground. How is your photography reframing the realities of ordinary people?

LT: My main interest is not to reframe realities but to raise questions, especially about the disconnection between those making decisions and the people of Afghanistan. For many years, I lived in Afghanistan and often saw foreigners come to work for international organisations or political bodies. They would live in the country for years, most of that time spent behind blast walls, inside secured compounds, with very limited access to the country itself. These were people in positions to make important decisions about Afghanistan, who only saw it from a helicopter. That’s the perspective of the aerial landscapes that open and close the book. The question I want to ask myself, and the viewer, is: How much did we actually understand of this place? How much were our views and representations complicit in an occupation? Did I truly look, or did I serve a colonial machine? How many layers of meaning did we miss because of the country’s complexity, or because a certain view of it was expected to make the occupation possible?

A: How has your time living in Afghanistan – and returning over many years – shaped your understanding of the narratives we miss or overlook?

LT: Like many photographers encountering Afghanistan for the first time, I too felt the need to construct the expected images of the country: the burqa, the Kalashnikov, the old man with the turban. But having the chance to stay for a long time gave me the opportunity to reflect on these visual clichés. Gradually, I began to focus on what I shared with people rather than on what I found strange or intriguing. Instead of starting from fascination or aversion toward a culture, I tried to see what simply is, without judgment. The point is not to move beyond the visual language of photojournalism, which is part of my cultural background and a tradition I respect, but to work on the complexity and depth of the message.

A: What do you hope people take away from reading the book?

LT: I hope it can be accessible on multiple levels. You can simply leaf through it and see some “beautiful” black-and-white images of Afghanistan. But if you give it time, you can go deeper. There’s a lot of intentionality in the sequencing, texts and choice of formats. I want viewers to enjoy their first encounter with the pictures, to take a tour through this world and then to have the opportunity to look again and be prompted to think more critically about what they’ve seen.

It Can Never Be The Same is published by GOST Books: gostbooks.com

Words: Emma Jacob & Lorenzo Tugnoli

Image Credits:

1. Lashkar Gah, Afghanistan, May 2021 © Lorenzo Tugnoli.

2. Herat, Afghanistan November 2022 © Lorenzo Tugnoli.

3. Wardak, Afghanistan October 2021 © Lorenzo Tugnoli.

4. Nangarhar, Afghanistan December 2019 © Lorenzo Tugnoli.

5. Kabul, Afghanistan February 2019 © Lorenzo Tugnoli.