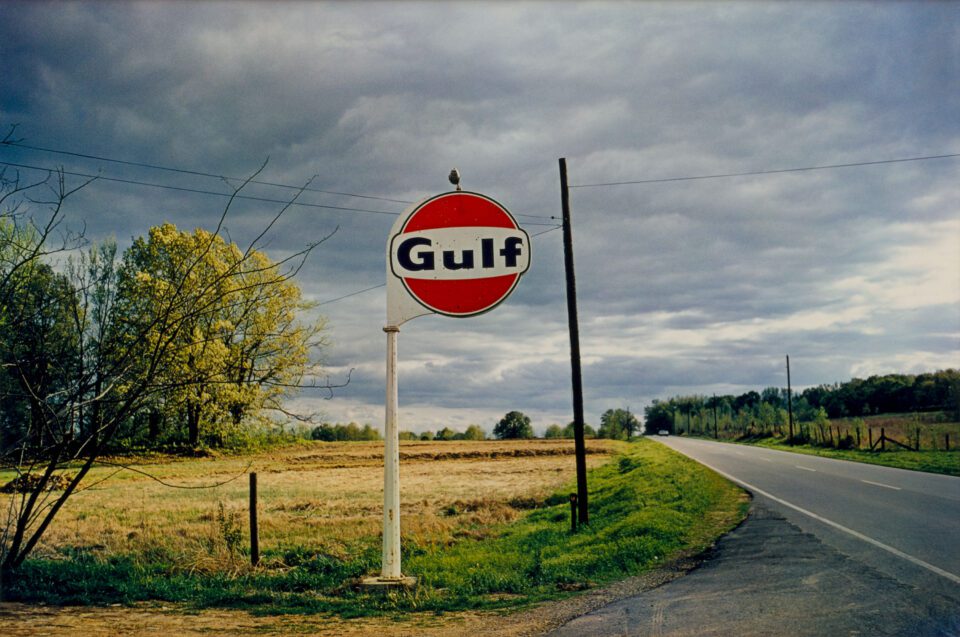

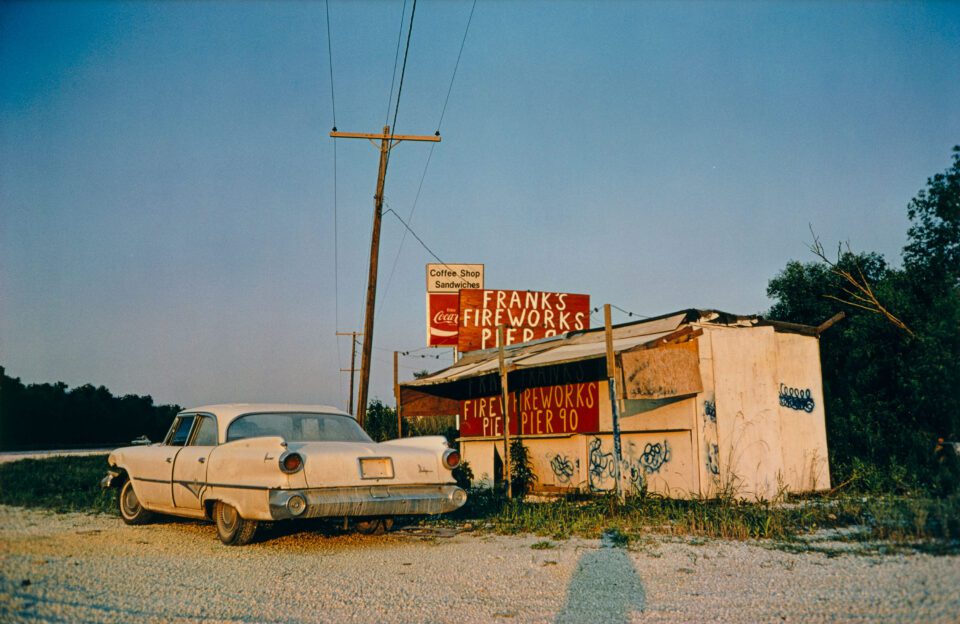

Few photographers have shaped the language of colour as decisively as William Eggleston. He showed that ordinary scenes, when observed with patience and precision, could carry the same weight as traditional subjects of art. His work refuses spectacle yet rewards close attention. By turning the camera on petrol stations, motels and suburban streets he proposed a democratic vision of what could be worthy of observation. This radical insistence on attentiveness transformed colour photography from novelty into a serious medium. Decades later the clarity and restraint of his vision remain revolutionary, although many who have come after have tried to emulate this mastery and they never fully achieve his brilliance.

Born in Memphis, Tennessee, in 1939, Eggleston’s sense of place was inseparable from his upbringing in the American South. The region appears in his work not as a theme but as lived environment defined by light, colour and spatial rhythm. He began photographing seriously in black and white before embracing colour at the end of the 1960s, a move that was philosophical rather than aesthetic. It allowed him to register psychological nuance embedded in everyday life. His photographs do not narrate the South; they capture its textures, moods and subtleties. He positioned ordinary objects and people as carriers of meaning.

Eggleston’s 1976 exhibition at The Museum of Modern Art in New York remains a turning point in photographic history. Critics initially struggled to understand why banal objects commanded such authority. Yet these images were meticulously composed, revealing his insistence on visual democracy. The accompanying publication William Eggleston’s Guide reinforced this new grammar, demonstrating that significance could reside in parking lots, signage and interiors. His method challenged hierarchical notions of subject matter, insisting that visual attention alone could confer importance. The exhibition set a precedent for generations of colour photographers who followed in these footsteps.

Institutional recognition arrived gradually but decisively. His work has been shown at the Corcoran Gallery of Art, the Barbican and Museum Ludwig amongst others. The 2008 Whitney Museum survey Democratic Camera highlighted both the breadth and consistency of his vision. More recent exhibitions at C/O Berlin, Fundación MAPFRE and The Metropolitan Museum of Art have reaffirmed his relevance for contemporary audiences. Eggleston’s photographs have aged without diminishing in authority, balancing formal rigour with lived experience. This enduring relevance underscores the care that informs every image.

David Zwirner’s The Last Dyes offers a rare opportunity to see Eggleston’s work in its original medium. The exhibition presents the final dye-transfer prints ever produced, a process Eggleston pioneered in the early 1970s. This method produces unmatched tonal depth and saturation, qualities that digital reproductions cannot replicate. Returning these images to their intended medium restores their physical presence and compositional authority. This exhibition is less an exercise in nostalgia than a reaffirmation of artistic intention. The prints reveal how medium, light and colour are inseparable.

The selection spans 1969 to 1974 and includes works from Outlands and Chromes, alongside images first shown at MoMA in 1976. Eggleston, with his sons, curated this collection, as a distillation of his early project. The choices are measured rather than exhaustive, emphasising equilibrium and clarity over narrative completeness. Each image isolates a moment of visual tension and harmony, demonstrating the precision of his perception. The exhibition allows viewers to engage with his methodical use of colour, light and composition. It presents a portrait of Eggleston’s working process at its most refined.

Exterior photographs exemplify the artist’s command of balance and spatial logic. Wide Southern skies stretch across the frame without overwhelming it. Buildings, cars and signage act as chromatic anchors, stabilising the composition. Decay or emptiness does not invite sentimentality; it registers with quiet authority. His landscapes neither romanticise nor critique – they simply exist in a meticulously observed visual world. The restraint in these images is a key factor in their enduring resonance.

Interior works demonstrate a contrasting intensity and sculptural approach to light. Darkened rooms are punctuated by highlights, producing a chiaroscuro reminiscent of classical painting. In one self-portrait Eggleston lies in a dim room, his head on a bright white pillow whose folds seem sculpted. Interiors like this reveal his ability to turn everyday spaces into controlled studies of light, form and presence. They underscore how Eggleston’s visual philosophy applies to both external and internal worlds.

Eggleston’s strength lies in merging formal sophistication with lived reality. People appear in his frames not as subjects to be interpreted but as components of a larger chromatic system. Clothing, gesture and posture function as much as compositional devices as narrative cues. The images maintain equilibrium between human presence and environment. This approach avoids both documentary distance and sentimental excess. It demonstrates how patient observation can generate meaning without explanation.

Comparisons to other photographers illuminate Eggleston’s legacy. Stephen Shore shares his focus on the vernacular, finding visual interest in motels, carparks and roadside architecture. Joel Meyerowitz, like Eggleston, embraced colour at a time when it was professionally risky, foregrounding light as a structuring principle. Viviane Sassen offers a contemporary counterpoint, using colour, geometry and abstraction to transform quotidian spaces into formally rigorous photographs. All three explore how visual attention and compositional care can elevate everyday subjects, and nothing is visually irrelevant.

Eggleston’s iconic status rests on his refusal to justify his vision. He did not seek spectacle or instruction but trusted the camera to register significance in the seemingly ordinary. His democratic approach treats all subjects with equal care, allowing meaning to arise through perception alone. This attentiveness remains just as radical today because it requires discipline and patience from both artist and viewer. His work endures because it models a way of seeing that is deliberate, calm and rigorous.

The Last Dyes confirms why Eggleston’s practice continues to matter. These final dye-transfer prints demonstrate how medium shapes perception and deepens meaning. The exhibition clarifies that colour, light and material are inseparable from the ideas they carry. It reinforces the vitality and relevance of his visual method. Eggleston’s legacy persists because he trusted attention itself as the foundation of art. The exhibition shows that innovation often begins with restraint, precision and patient observation.

William Eggleston: The Last Dyes is at David Zwirner, New York until 7 March: davidzwirner.com

Words: Anna Müller

Image Credits:

1&6. William Eggleston, Untitled, 1971 © Eggleston Artistic Trust. Courtesy Eggleston Artistic Trust and David Zwirner.

2. William Eggleston, Untitled, c. 1970 © Eggleston Artistic Trust. Courtesy Eggleston Artistic Trust and David Zwirner.

3. William Eggleston, Untitled, 1971 © Eggleston Artistic Trust. Courtesy Eggleston Artistic Trust and David Zwirner.

4. William Eggleston, Untitled, 1973 © Eggleston Artistic Trust. Courtesy Eggleston Artistic Trust and David Zwirner.

5. William Eggleston, Untitled, 1972 © Eggleston Artistic Trust. Courtesy Eggleston Artistic Trust and David Zwirner