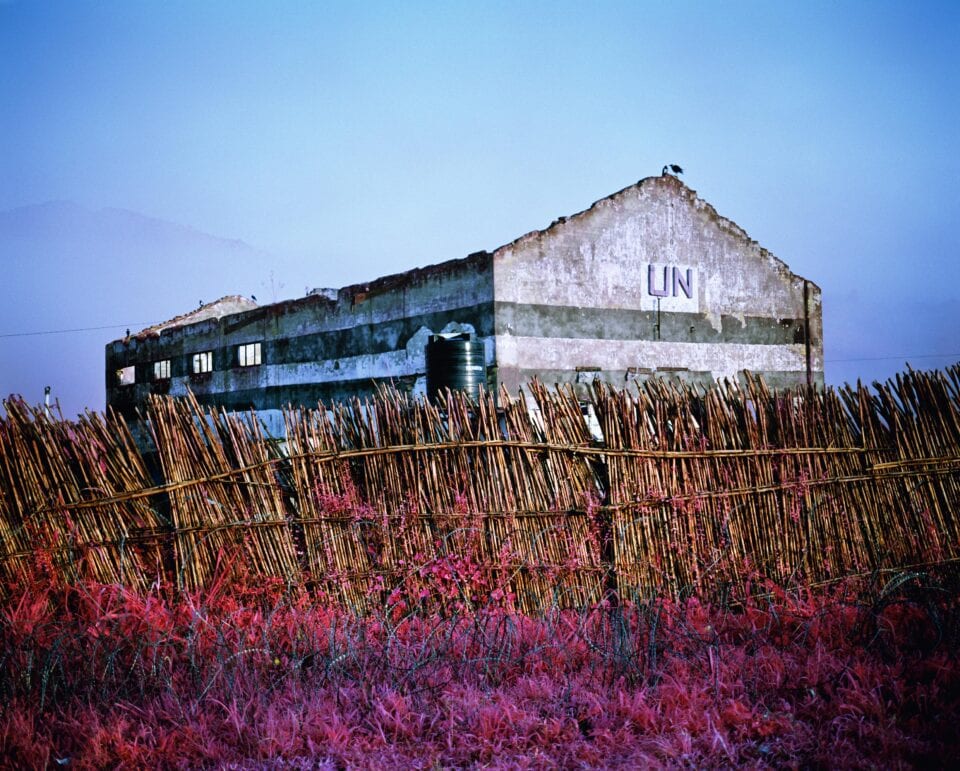

Hot pink is not a colour normally associated with war. The colour of flamingos, of candy floss and Barbie dolls, it feels playful, even frivolous somehow. So when Irish-born photographer Richard Mosse (b.1980) portrayed conflict in the eastern Democratic Republic of Congo in vibrant pink hues in his series Infra, the effect was unforgettable – hypnotic, beautiful, jarring. Shot using Kodak Aerochrome, a military film technology conceived in the Second World War to identify camouflaged subjects and discontinued in 2009, his images pop with the unexpected colour, transforming the region’s verdant rainforests and the uniforms of Congolese soldiers and rebels.

“Somehow the way he has done it both repels and attracts you – it gets you completely immersed in the subject matter,” Brett Rogers, director of the Photographers’ Gallery and chair of the panel that awarded Mosse the 2014 Deutsche Börse Photography Foundation Prize, told the Guardian at the time. Mosse is one of a generation of artists behind the conceptual turn that a strand of documentary photography has undergone in recent years. These photographers strive to make their viewers conscious of photography’s limitations and its inherently flawed claims to objective truth by bringing in elements of fiction or by using, as Mosse does, a highly stylised visual language that forces us to look at familiar subjects in a different way.

Displaced, the first retrospective exhibition of Mosse’s work, is currently on show at Fondazione MAST in Bologna, Italy, showcasing 77 large-scale images, installations and videos made between 2010 and the present. It chronicles how his approach has developed over time. As well as Infra and its sister project, the multimedia installation The Enclave (2013), the exhibition features his 2017 Prix Pictet-winning stills and film Heat Maps and Incoming (2017). Like the earlier works, these were created using military imaging technology, this time a thermal heat camera that can detect body heat from 30m away and is illegal under international law.

Again mesmerising and disturbing, the photographs show refugees travelling on routes into Europe as ghost-like figures. They force the viewer into an uncomfortable position, revealing the dehumanising way migrants are treated and portrayed. The series is part of a wider conversation into the ethics of the genre, with critics asking whether certain types of imagery contribute to the ‘othering’ of those depicted. More recently, Mosse has turned his lens from social to environmental issues. He travelled to the Amazon rainforest in Brazil to shoot Ultra and Tristes Tropiques, using UV fluorescence and satellite imaging technology to show – from up close and afar – a region that is enduring catastrophic levels of deforestation. The jewel-like portraits of plants and psychedelically-tinted land mappings create the same sense of wonder found throughout Mosse’s work. As elsewhere, that appeal reveals troubling realities.

Displaced runs until 19 September at Fondazione MAST, Bologna. Visit mast.org.

Words: Rachel Segal Hamilton.

Image Credits:

1. © Richard Mosse, Hombo, Walikale, eastern Democratic Republic of Congo, 2012. Courtesy of the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York.

2. © Richard Mosse, Come Out (1966) V, eastern Democratic Republic of Congo, 2011. Private collection SVPL

3. © Richard Mosse, Mineral Ship, Crepori River, State of Para, Brazil, 2020. Courtesy of the artist and carlier | gebauer, Berlin/Madrid

4. © Richard Mosse, Dionaea muscipula with Mantodea, Ecuadorean cloud forest, 2019 Courtesy of the artist and carlier | gebauer, Berlin/Madrid.

5. © Richard Mosse Platon, eastern Democratic Republic of Congo, 2012. Collection Jack Shainman