Review by Rosa Abbott

The Irish Museum of Modern Art is celebrating its 20th anniversary with Twenty – an exhibition drawing upon its existing collections to showcase the works of 20 of the most exciting contemporary artists it has acquired pieces from. The artists selected are linked predominantly by matter of circumstance, and not so much by aesthetic. All are Irish, or have a special relationship with Ireland (though many live abroad). All are around about twice the age of the twenty-year-old IMMA, and are on the cusp of establishing a solid international reputation. But beyond these three binding factors, the emphasis is on diversity, and so Twenty becomes a theme-less exhibition made up of various media, the only agenda being that of the institution itself: to celebrate the art that is being produced right now.

Painting is well represented in Twenty with works by abstract artists Fergus Feehily and Patrick Michael Fitzgerald; a William McKeown series titled Tomorrow and appropriated imagery from Nevan Lehart (who pillages the archives of that other avid appropriator, Richard Hamilton). However the downside of exhibiting painting in a multi-disciplinary exhibition such as this one is that the works can be easily overshadowed by the scale and three-dimensionality of adjacent pieces. It’s no surprise then that the most commanding work to be hung from a wall is Stephen Brandes’s contribution, Chandelier – an intricately decorated piece of floor vinyl measuring almost four metres by three metres. Brandes painstakingly recreates “a perpetually reinvented fictional world”, mapped out as a series of floating islands radiating from one central dystopian creation, in an arrangement resembling a light fitting.

Sculpture is a stronger area, with works coming from Corban Walker, Ireland’s representative at this year’s Venice Biennale, and Eva Rothschild – who is currently the subject of a large-scale show at the Hepworth Gallery in Wakefield. These two names in particular stand out as artists who are becoming increasingly prominent on the international stage, and both their structures live up to their escalating reputations. Walker’s architectonic glass sheets glint in the light that radiates through IMMA’s windows – turning the static and angular work into a more fluid experience with the viewers’ movements. Rothschild, on the other hand, creates an atmosphere of threat with the jutting black spikes of Stalker (2004).

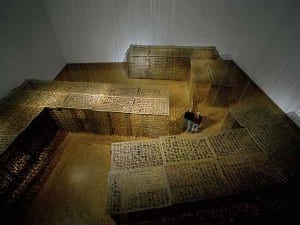

Katie Holton’s 137.5º/It Started on the C train (2002) is another highlight. A seemingly chaotic sprawl of plant-like forms, the work looks like an organic exploration of nature stereotypically appropriate to her feminine materials of Irish lace crochet. However the artist claims the piece is actually governed by rigorous scientific and mathematical theorems, from the age-old Golden Ratio and Fibonacci series to maps of the artists’ Carbon Footprint – challenging the initial ‘feminine’ connotations of the work and thus undermining the binaries which give rise to such reductive divisions. It seems to be in installations such as these that IMMA’s Collection finds its strength: equally thought-provoking discourse is generated by the other installation artists in the exhibition, such as Liam O’Callaghan, Alan Phelan, Niamh McCann and Sean Lynch.

There are also several film works on show, the most effective of which is Hereafter (2004), by Patrick Jolley, Rebecca Trost and Inger Lise Hansen. It is a harrowing depiction of Ballymun Flats – a notorious set of tenement housing blocks in a poverty-stricken area of North Dublin that is currently facing ongoing demolition. Dramatically set to a hauntingly entrancing soundtrack, the beautifully shot film documents the decay and destruction of the infamous structure in the final days before its demise. Abandoned bedrooms are left with cut outs from cheap teen magazines still adorning the walls. Water drips down, slowly filling the desolate homes with a dusty solution. Furniture crashes through a hole in a ceiling at the tension-swelling climax to the piece.

Though the visual impact of this film is no doubt any less for the many tourists who pass through IMMA’s doors, for Dubliners, Hereafter packs an extra punch due to the subject matter. Ballymun has acquired an almost iconic status (albeit as a symbol of destitution) since its erection in the seventies; the familiarity and recentness of the work contribute to its aesthetic effect when exhibited in Dublin. This is also, in a sense, the case for the exhibition en masse. After all, the selection criteria for Twenty is defined by spatial and temporal proximity, using recent works from artists linked to Ireland. The exhibition is thus somewhat unavoidably steeped in the specificities of a singular time and place, and though the artists’ approaches may vary, the collection works fairly accurately as a snapshot documenting where Irish contemporary art is right now. Whether that art is more affecting because of it’s proximity time can only tell, but right now, it’s looking pretty good.

Twenty continues until October 31 at the Irish Museum of Modern Art, Dublin.

Aesthetica Magazine

We hope you enjoying reading the Aesthetica Blog, if you want to explore more of the best in contemporary arts and culture you should read us in print too. In the spirit of celebration, Issue 41 includes a piece on Guggenheimn Bilbao where the Luminous Interval features internationally acclaimed artists such as Louise Bourgeois, Kiki Smith and Damien Hirst, ArtAngel’s new commission at MIF, Bruce Nauman’s retrospective at The Kunsthalle Mannheim and Cory Arcangel’s Pro Tools at the Whitney in NYC. You can buy it today by calling +44(0)1904 479 168. Even better, subscribe to Aesthetica and save 20%. Go on, enjoy!

Image:

Courtesy of the artist and Thomas Dane Gallery, London.