Who is visible in photography, and whose stories have been left out? This is the question at the heart of Cripping the Lens, a new exhibition from This is Gender, a global visual platform that uses art as tool for activism. Each year, the organisation runs the world’s largest photography and visual arts competition centred on gender justice. Now in its fifth year, the 2025 edition turns its attention to the intersection of gender and disability. The show features 50 original artworks and spans continents, cultures, identities and perspectives, exploring how social structures shape what we see and who gets seen. It is a powerful collection, presenting artists like Jaime Prada, whose image The Past in Your Hands centres a blind woman who explores an ancient sculpture through touch, challenging ableist norms and exposing how cultural access remains a privilege, not a right. Elsewhere, Acompañamiento Y Cariño by Jenny Bautista Media reveals an intimate moment between two disabled partners, reframing love as an act of mutual strength. At a moment when disability rights are being rolled back globally – from shrinking access to support, to the resurgence of institutionalisation – this exhibition offers a necessary intervention. Imogen Bakelmun, Curator and Founder of This is Gender, spoke to us about what it means to Crip the Lens.

A: What sparked the idea for Cripping the Lens: Gender, Disability, and the Politics of Visibility?

IB: As part of Global 50/50 – an initiative dedicated to gender, health and justice – we use data to expose global inequalities. Over the past five years, This is Gender has extended that mission into visual culture, inviting artists to reflect on how gender shapes everyday life across the world. But when we looked back at our growing archive, one thing was clear: disability was profoundly underrepresented. Not just in subject matter, but as a lens through which to question the systems we aim to dismantle. At the same time, we are witnessing a resurgence of institutionalisation, stalled legal protections and shrinking support for disabled communities worldwide. From welfare cuts in the UK, to weakened civil rights enforcement in the US and delayed anti-discrimination laws across Asia and Latin America, hard-won gains are being eroded. Cripping the Lens is our response. It invites viewers to look again, to reframe how we think about bodies, identities and the politics of being seen. Gender and disability are not separate categories. Gender shapes how disability is read; disability reshapes how gender is lived. By centring this intersection, we wanted Cripping the Lens to become more than an exhibition, and rather a counter-archive and space for resistance

A: You’ve said gender and disability collide, overlap and reshape one another. In what ways did this idea inform your curatorial approach?

IB: From the outset, we approached gender and disability as intertwined forces that shape how bodies are lived, read and represented. This conceptual starting point shaped every aspect of the curatorial process; what we selected, how we framed it and the values that guided our decisions. At This is Gender, our curatorial ethos has always been to reflect the diversity of global gender experience; placing amateur work alongside photojournalism, polished portraiture beside raw, intimate images. With Cripping the Lens, we engaged directly with the legacy of disability justice movements and the artists and activists who have long challenged what counts as legible, beautiful or worthy of attention. To crip the lens is to follow in their footsteps. It means bending the camera away from spectacle and toward resistance and images shaped by care, survival, protest, and pleasure. Access, for us, was also part of the curatorial method, not a set of technical add-ons, but a relational practice. It meant slowing down, sharing power with artists, and remaining open to feedback that could reshape the project itself.

A: This exhibition spans more than 800 submissions from around the world. What guided the selection process across such a vast archive?

IB: With so many submissions, selecting the final works was no small task, and not one we undertook alone. We depended on the skill, experience and insight of an exceptional judging panel composed of disabled artists, curators, and cultural practitioners. Their lived experience and creative expertise were central to shaping the exhibition. Each year, This is Gender runs an open call around a critical theme, and over time, we’ve developed a curatorial methodology that balances artistic quality, storytelling strength and political or personal insight. For Cripping the Lens, we placed particular emphasis on works created by disabled artists and those from historically marginalised geographies, voices too often excluded from dominant visual narratives. We avoided tropes of tragedy or inspiration, and foregrounded work that disrupted simple narratives. Works that challenged not just what we see, but how we see. Many of the longlisted works now appear outside of our core exhibition in our official This is Gender collection.

A: We live in a time where equality rights and hard-won gains are being increasingly rolled back. How can art confront erasure and act as a form of resistance?

IB: Art resists erasure by insisting on presence. At Global 50/50, our work is grounded in data and evidence. In This is Gender, these visual artworks sit in active dialogue with that research. Together, they expand what evidence can look like, revealing how visual storytelling can expose harm, resist reductive narratives and demand justice. In a world saturated by images, the way we depict gender has real-world consequences, but too often we only see a single image of what is complex and diverse. Inspired by Chinua Achebe’s call for a “balance of stories,” we centre intersectional perspectives that challenge power, illuminate complexity and insist on representation that is reflective, plural and accountable. In doing so, we treat art not as an accessory to advocacy, but as a vital form of resistance.

A: How do the works featured disrupt mainstream ideas of what disability “looks like”?

IB: There is no one face of disability, no single narrative, no fixed image. The works featured here challenge the narrow and often dehumanising tropes that dominate visual culture: the tragic, heroic, sanitised. Instead, you will find meditations on chronic illness, expressions of queer kinship, documentation of systemic neglect and declarations of joy. They offer complex, embodied perspectives, sometimes raw, sometimes playful, always honest. Whether through the intimate framing of pain, radical presence of joy, or everyday moments that rarely make it into public discourse, these artists ask us to see differently. Not only to look at disabled lives, but to recognise how the systems we move through shape what is valued.

A: The exhibition insists that care is power and joy is resistance. Why was it important to centre joy in this context, especially in stories so often framed through struggle?

IB: Too often, disability is understood through pity, sacrifice or hardship – narratives that flatten experience and obscure agency. But the works we received resist that. We were struck by how many artists offered not just critique, but creation: alternative ways of living, loving, parenting and being. Joy pulses through this exhibition, not as escapism, but as defiance. These artists show how pleasure, protest, play and imagination can become strategies for survival and transformation. Care, too, is redefined. Not something done todisabled people by others, often filtered through gendered assumptions of duty or dependence, but through the cripp’d lens we learn to see it as an act of agency, intimacy and resistance. It’s how disabled communities sustain one another, challenge isolation and refuse the systems that devalue their lives. These works insist: disabled life is not a deficit, but a generative force. In turn, we wanted to highlight joy and care not as soft themes, but as political, radical and central to reimagining the world.

A: The show was launched in collaboration with the feminist international human rights organisation, CREA, and Canada’s largest disability arts organisation, National Access Art Centre. How important were these collaborations in curating the show?

IB: They were essential. In coming from a background rooted in gender and social justice, we recognised early on that we needed to partner with experts deeply embedded in disability rights and culture to ensure the exhibition’s integrity and accessibility. Working with CREA and the National Access Art Centre helped us entrench accessibility not only in curation but also in promotion and outreach. Their guidance was invaluable, and these lessons will continue to shape our future projects. Our judging panel included representative from National Access Art Centre including disabled artists and curators Asha, Carla S, Eve Johnson, Kathy M Austin, Mark Bedford and Sherrine Fox, whose reflections and feedback were critical in shaping the exhibition’s direction. Through CREA, we also engaged visual culture experts Carbon and Shamim Salim, who brought rich depth and nuance. Their insights, shared openly in video reflections, remain a vital part of the conversation around the show.

A: What do you hope audiences take away from viewing Cripping the Lens?

IB: Cripping the Lens demands more than passive observation. It calls viewers to reckon with how disabled lives are erased, distorted or romanticised, especially at the intersections of gender, race and class. At a time when commitments to equity are under threat, the exhibition asserts that access is not charity, it’s justice. We hope audiences leave seeing disability not as lack, but as a force for collective reimagining.

A: Looking ahead, what does the future hold for This is Gender?

IB: The future of This is Gender is about growth, boldness and deeper connection. We’ll continue launching annual competitions and exhibitions that explore gender in all its complexity and diversity, amplifying voices often left out of mainstream narratives. A core focus is decolonising how gender and identity are visualised in development, challenging outdated, reductive imagery and insisting on representation that reflects lived realities. At its heart, This is Genderremains a platform for urgent, transformative work, using art to disrupt, connect and envision more just futures.

Cripping the Lens is available to view online: thisisgender.global5050.org

Words: Emma Jacob & Imogen Bakelmun

Image Credits:

1. Sadman Sakib (Bangladesh), Hope Never Dies.

2. Tekle Gulordava, The Air is Not For Us. Batumi, Georgia. 2025.

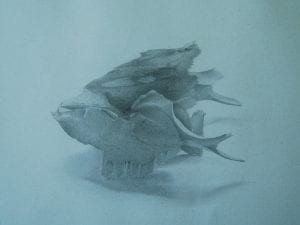

3. David Olayide, If Fishes Could Talk, Osogbo, Nigeria. 2023.

4. Jenny Bautista Media, Acompañamiento Y Cariño. Mexico City, Mexico. 2025.

5. Ziaul Huque, Cricket is my Emotions, Hathazari, Chattogram, Bangladesh. 2024.

6. Jordiana Carroll, Accessibeach. Pensacola, Florida, USA. 2025.