There is an extraordinary power in the image. It arrests, provokes, seduces and confesses. Photography, once the preserve of specialists and shuttered darkrooms, is now ubiquitous. Its reach is planetary. Each day, over 95 million photographs are uploaded to Instagram – a ceaseless cascade of observation and expression. This democratisation of image-making has transformed photography from a medium of documentation into a global lingua franca. It has become how we speak, how we remember, how we reckon with our present. In a world saturated with visuals, the need for spaces that decelerate the image – granting it space to resonate, to be questioned, to breathe – has never felt more urgent.

This July, Dublin responds with bold clarity. PhotoIreland, a longstanding force in the visual arts landscape, unveils the International Centre for the Image in the city’s North Wall, a newly established 10,000 square-foot cultural space rooted in the Coopers Cross district. Developed in partnership with Kennedy Wilson and supported by the Arts Council of Ireland, the centre represents a defining moment for contemporary image-making in Ireland. It consolidates PhotoIreland’s broad portfolio under one roof and offers an ambitious year-round programme of exhibitions, education and public engagement – all free to access.

The Centre is a destination for creatives, fostering a vital arts ecosystem. It features artist studios, a public workshop, a dedicated art library and a bookshop – spaces of research, production and presentation held in meaningful proximity. The emphasis here is on fostering sustainable practices, nourishing emerging artists, and deepening the conversation around visual culture in all its forms. As Ángel Luis González Fernández, Director of PhotoIreland, puts it: “The International Centre for the Image will open new opportunities for people to engage with the world of photography and the visual arts. Our ambition is to create a cultural destination that attracts leading international and Irish artists, provides workspace to emerging local artists, and connects with the community and its rich history.”

At Aesthetica, we are particularly excited to witness this milestone. PhotoIreland has consistently interrogated and expanded the role of photography across borders, and the establishment of a permanent home signals an evolution not only for the organisation but for Irish arts infrastructure. This new centre is a proposition: that image culture deserves a physical space to be explored with depth, rigour and care.

It opens with Foreword, an inaugural exhibition co-curated by González Fernández and Julia Gelezova. It brings together 17 local and international artists working across photography, video, installation and immersive media. But Foreword resists the format of a greatest-hits showcase. Instead, it articulates the curatorial focus of the Centre: the moving and still image as a critical tool, a way to speak to and through the cultural moment. These are works that think with the image, challenging systems beneath the surface.

Abigail O’Brien’s Justice – Never Enough interrogates misogyny as filtered through film and media, using the iconic Aston Martin to unpack deep-seated codes of gendered power. Alan Butler’s 100 Years of Solitude explores landscapes within video games using 19th-century wet plate processes, revealing the ideological stasis beneath technological evolution. Meanwhile, Alex Prager’s film Run is a technicolour expression of psychological unease in an unstable world – a tightly wound narrative of escape and anxiety.

The show is as intellectually charged as it is sensorial. Basil Al-Rawi’s House of Memory, a virtual reality experience drawing from the Iraqi diaspora, reconfigures the archive as lived encounter. In Bereitschaft, Ana Zibelnik and Jakob Ganslmeier examine how extremist movements co-opt the aesthetics of social media to amplify their narratives, offering a sobering study in visual manipulation. Penelope Umbrico’s Sunset Portraits from Flickr Sunsets, exhibited in Ireland for the first time, speaks to a compulsive image culture—millions photographing the same motif, chasing uniqueness in uniformity.

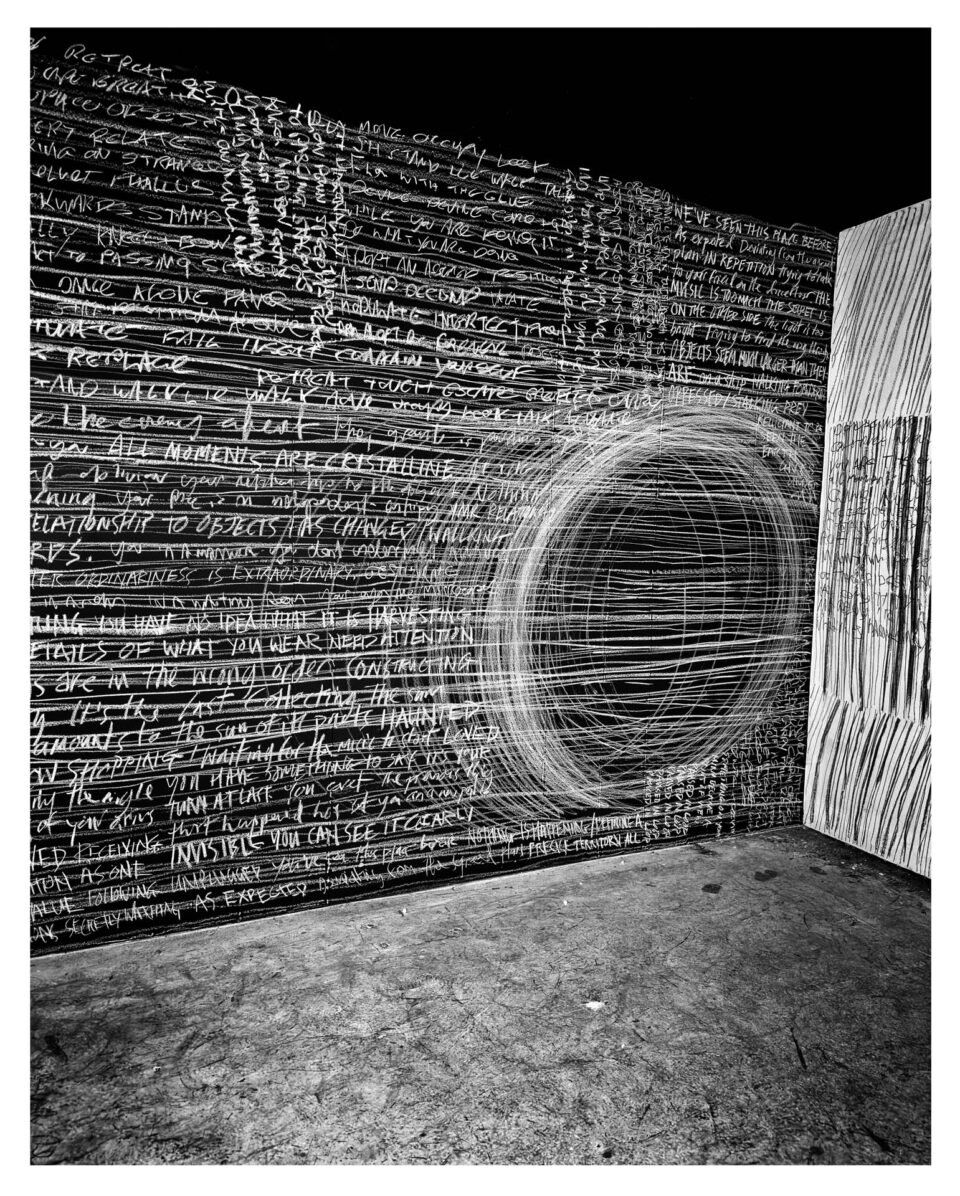

There is autobiography, too. Anna Ehrenstein’s Melody For A Harem Girl By The Sea blends personal history and cyborg feminism into a surreal investigation of identity within hyperconnected visual systems. Jean Curran’s Spring, a new assemblage-based work, marks a pivot from cinematic references towards more intimate visual language, framed through a painterly lens. Colin Martin’s Unreal Apocalypse wrestles with the slippery threshold between real and virtual, questioning how synthetic environments shape us.

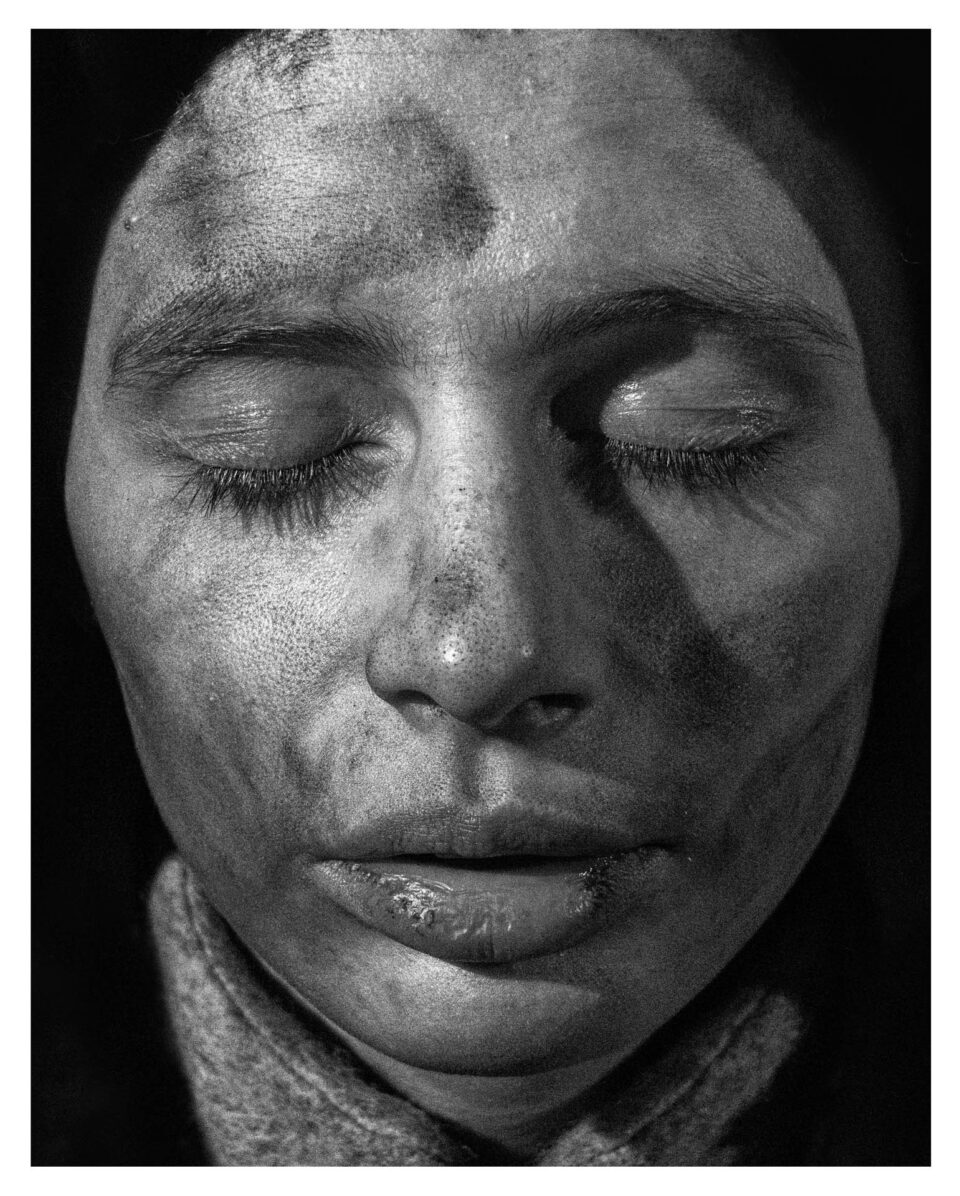

Other works dwell on loss and transformation. David Farrell’s Lugo Lament reflects on the destruction of his personal archive in the 2023 Italian floods, while Dominic Hawgood’s Vestige Node probes the ritualistic nature of digital environments and their echoes in generative AI. And there are glimpses of what lies ahead: Eamonn Doyle offers a preview of AS IF, a major interdisciplinary work to be shown at the Centre in 2026, continuing his investigation into rhythm, presence and photographic form.

Foreword doesn’t seek resolution. It feels more like a manifesto than a retrospective: a layered, contradictory and invigorating portrait of photographic practice today. It presents the image not as a fixed object but as a living, volatile agent – a site where identity, memory, and power converge and dissolve.

The Centre isn’t just a new gallery launch. It is a cultural proposition rooted in equity, sustainability and experimentation. It challenges the assumptions of traditional museum models and gestures towards a future where art is co-produced, re-examined and continually reshaped. In an era where images are created and discarded in milliseconds, Dublin has carved out a space for photography to be slowed, reconsidered and felt. The International Centre for the Image is, in every sense, a place to begin again.

International Centre for the Image, Dublin, opens 17 July.

Words: Shirley Stevenson

Image Credits:

1. Penelope Umbrico, Sunset Portraits from 8,462,359 Sunset Pictures on Flickr, 2010 – ongoing.

2. © Alex Prager. Film Still from Run (2022). Courtesy Alex Prager Studio and Lehmann Maupin, New York, Seoul, and London. International Centre for the Image, 2025.

3. © Eamonn Doyle, from AS IF. Courtesy of the artists. International Centre for the Image, 2025.

4. © Eamonn Doyle, from AS IF. Courtesy of the artists. International Centre for the Image, 2025.

5. © Alex Prager. Film Still from Run (2022). Courtesy Alex Prager Studio and Lehmann Maupin, New York, Seoul, and London. International Centre for the Image, 2025.