There has never been a more important time to consider our relationship with the environment. Camden Art Centre’s new show, The Botanical Mind, looks at the links between plants, humans and the universe – revealing the connections that bind us across 500 years of art.

Curator Gina Buenfeld discusses what viewers can expect from the show – delving into the complex cultural histories that underpin the exhibition, whilst exploring the variety of artworks on display.

A: The exhibition delves into the world of “plant intelligence.” Where did the idea for the show come from, and what does this concept involve?

GB: The Botanical Mind is a meditation on the being of plants: the alchemical magic they perform; and how they have developed sophisticated aesthetic languages to attract insects and birds to pollinate for them – a form of intelligence in nature that operates not by rational thought, but through the senses. It is inspired by the vast botanical knowledge of indigenous peoples in the Amazon, founded on an understanding of plants as spiritual entities that can heal not only the physical body, but the mind and spirit. For them, sacred plants like Ayahuasca are at the centre of their cosmology, and open up transcendent, transformative states of mind.

Following the scientific revolution, the notion of there being an implicit spiritual principle in the material world was abolished, and our consideration of plants has since been defined by their decorative function, or chemical and pharmaceutical constituents. Recently, however, the question of whether consciousness exists in non-human entities like plants has gained new interest in both science and the humanities. “Panpsychism” is a philosophy of mind that imbues all aspects of the material world with a spiritual dimension, and recent work in plant ontology, speculative realism, processual science and quantum physics has displaced human-being from the centre of our enquiries.

This exhibition reappraises some of those lost wisdom traditions and celebrates the magic and mystery of the botanical kingdom.

A: Why do you think images of plants have such a strong presence in the history of art across the globe?

GB: Plants are full of beauty – their shapes and colours repeat and divide in kaleidoscopic patterns. The arrangement of their petals and leaves follow mathematical principles (like the Fibonacci sequence) that are mirrored throughout the universe – sacred geometries that intimately relate each part of the cosmos to the whole. From the arrangement of Camelia and Dahlia petals, the seeds in a sunflower head or the fractals of Romanesco cauliflower, these patterns exhibit motifs that share the same characteristic as the whole, repeating shapes that regress or progress in scale infinitely. Sometimes described as the ‘fingerprint of god’, they could be thought of as blueprints for the natural world and recur in religious aesthetics globally.

In many Native American traditions – including the Andean Weavers of Peru that inspired Anni Albers’ work – cosmological designs are woven or embroidered as textiles, including abstract motifs that represent sacred and medicinal plants. The designs of Art Nouveau trace their origins to the plant world, and the mandala, the logarithmic spiral and arabesques of plant morphology can be seen emulated in Hilma Af Klint’s paintings, Nordic Viking ornaments, the Neolithic carvings of our ancient ancestors, flourishes from Roman architecture, stained glass windows in medieval churches and Islamic mosaics. These forms lend themselves to degrees of naturalism and abstraction: at once figurative (resembling the plant itself) and abstract (extrapolated as geometric patterns). The presence and meaning of patterns in the natural world and in art was a starting point for this exhibition. What at first might seem decorative or ornamental points to an implicit logic or form of consciousness that can be associated with all aspects of the living world, and even the most fundamental aspects of matter.

A: How does the show move beyond the art world – exploring the realms of literature, science, philosophy and historical artefacts?

GB: It’s not widely known that Carl Jung was an artist as well as a psychotherapist, and that his work was informed by alchemical literature and Eastern mysticism. Many of the artists in the exhibition also looked to the spiritual disciplines of tantra and meditation, as well as to the ceremonial use of psychoactive plant medicines to explore consciousness and the potential alchemy of the mind. These are ways of knowing and experiencing that are, for the most part, precluded in the west by the presuppositions (and superstitions) of secular modernity.

A: Does The Botanical Mind tap into dialogues surrounding the current environmental crisis?

GB: The exhibition was originally planned to open on Earth Day (22 April) but was inevitably postponed. During the period of enforced stillness since, we have all become plant-like: tethered to our homes, watching the shifting weather conditions and the plants that grow outside, colonising areas now left untended by humans. This has brought about a heightened sensitivity to environment, and there may never have been a more important time to reflect on our place in the natural order – we have decimated the world’s resources, polluted our air and water, and are now forced to realise how vulnerable we are to nature’s forces. I hope the exhibition will renew an interest in the mythologies that relate us to the archaic past, and to future generations who will live with consequences of our actions.

A: The exhibition features over 50 artists spanning 500 years. What are your highlights?

GB: The paintings of outsider artists Josef Kotzian, Anna Zemankova and Ana Haskel show a fascination with the strangeness of plant life. We’ll be showing a new painting by London-based painter Simon Ling, made on-site at Camden Art Centre over several months, through intense, sustained observation of the trees and landscape outside the building. The paintings, drawings and films of Henri Michaux, Joachim Koester, Bruce Conner and Jordan Belson take you into the inner realm of the mind, and show the hallucinatory images that emerge under the influence of Mescaline and Psylocibin mushrooms.

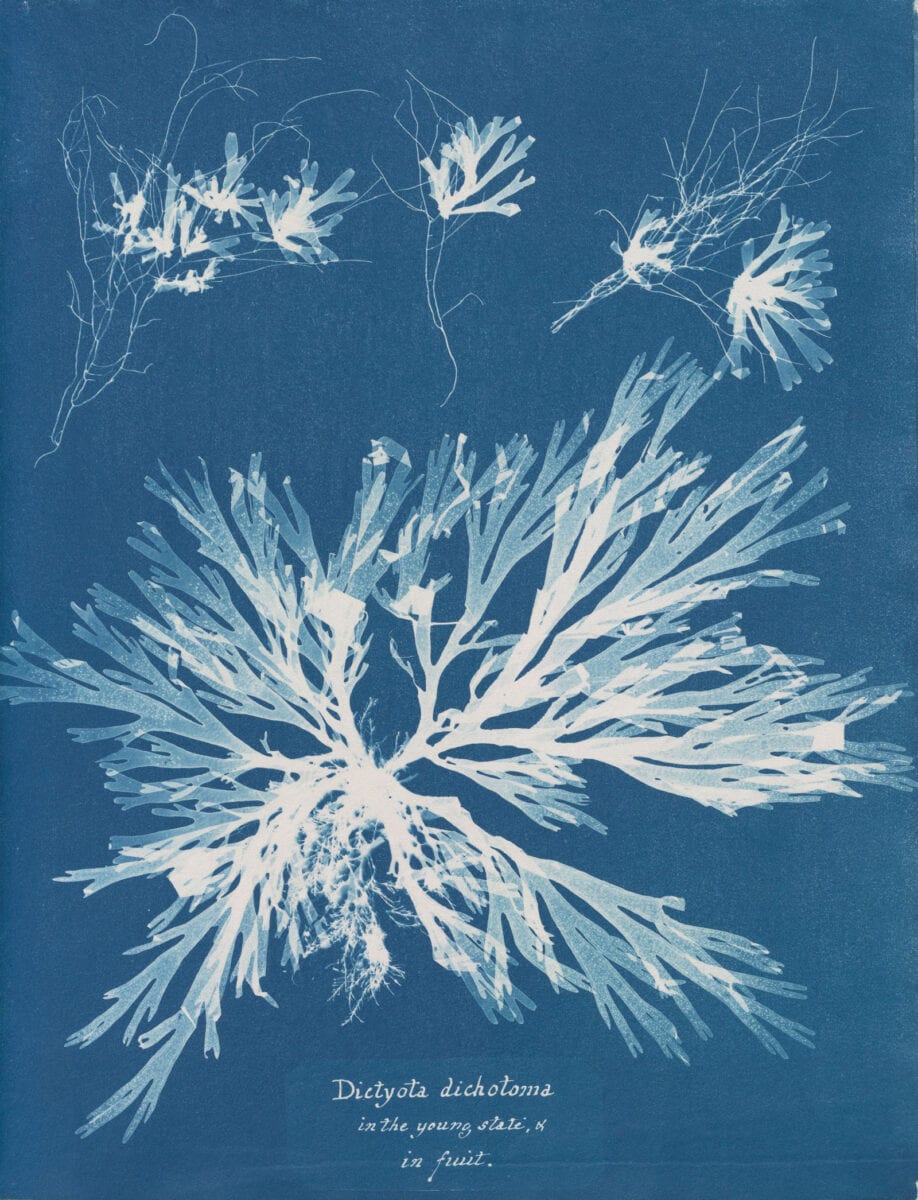

In a new film, James Richards & Steve Reinke have reworked images of the body from archival medical photographs, late 19th century zoetrope animations, microscopic and nebulae-like forms spanning the micro-and macro spectrum, and a psychedelic flicker through retinal images, that seem to lay vision open to what is inside the mind. We are also showing rare books and botanicals including a 15th century edition of the Ortus Sanitatis, Ernst Haekel’s Art Forms of Nature, Anna Atkins’ Cyanotypes and an extraordinary facsimile of the Voynich Manuscript – an enigmatic medieval botanical that is written in an undeciphered script, filled with images that describe a cosmology in which plants are esteemed with particular significance, connecting humans to the celestial realm.

A: Featured here are images by Anna Atkins and Karl Blossfeldt. What connects their work?

GB: Photosynthesis is a kind of alchemy. Sunlight captured on the surface of leaves converts the elemental properties of chlorophyll, oxygen and water into a profusion of complex forms, allowing the natural world to speak in images. Using light-sensitive membranes to create pictures, the photographic process shares a similar magic. Anna Atkins (1799 – 1871) was a botanist and pioneer of the cyanotype – a proto-photographic process that occludes an area of photosensitive paper with an object, creating a silhouette when the exposed areas transform to an intense cyan blue. Atkins collected seaweed specimens and the first images she made were of British algae, later incorporating ferns and flowering plants.

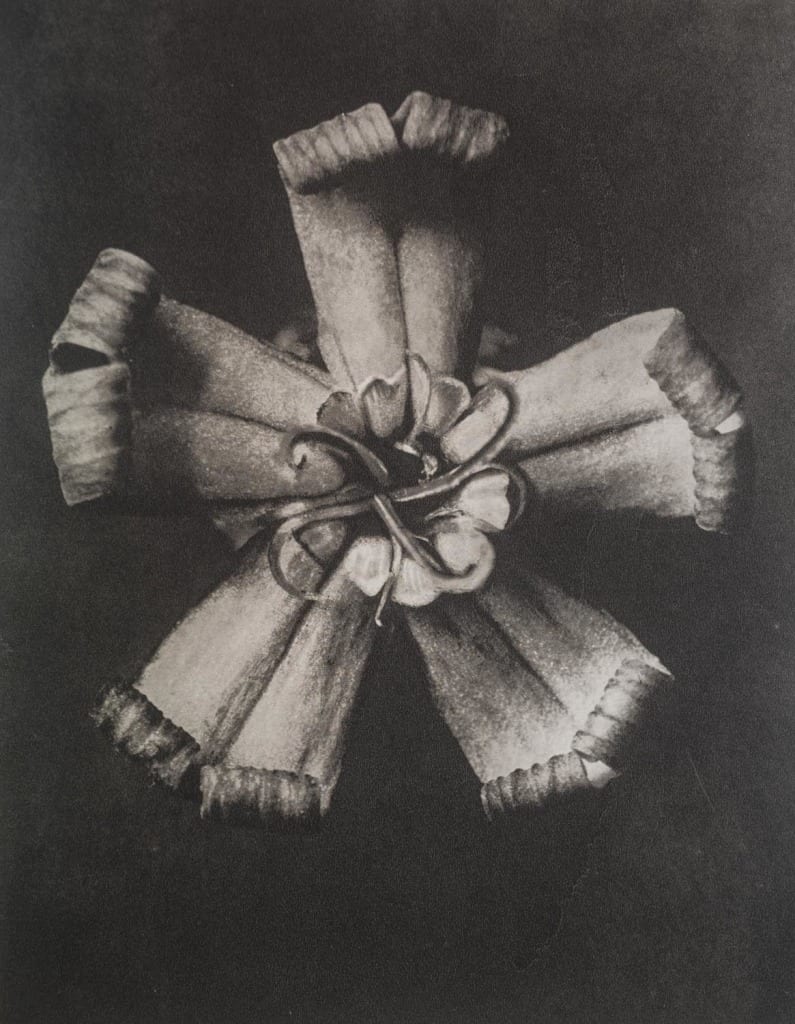

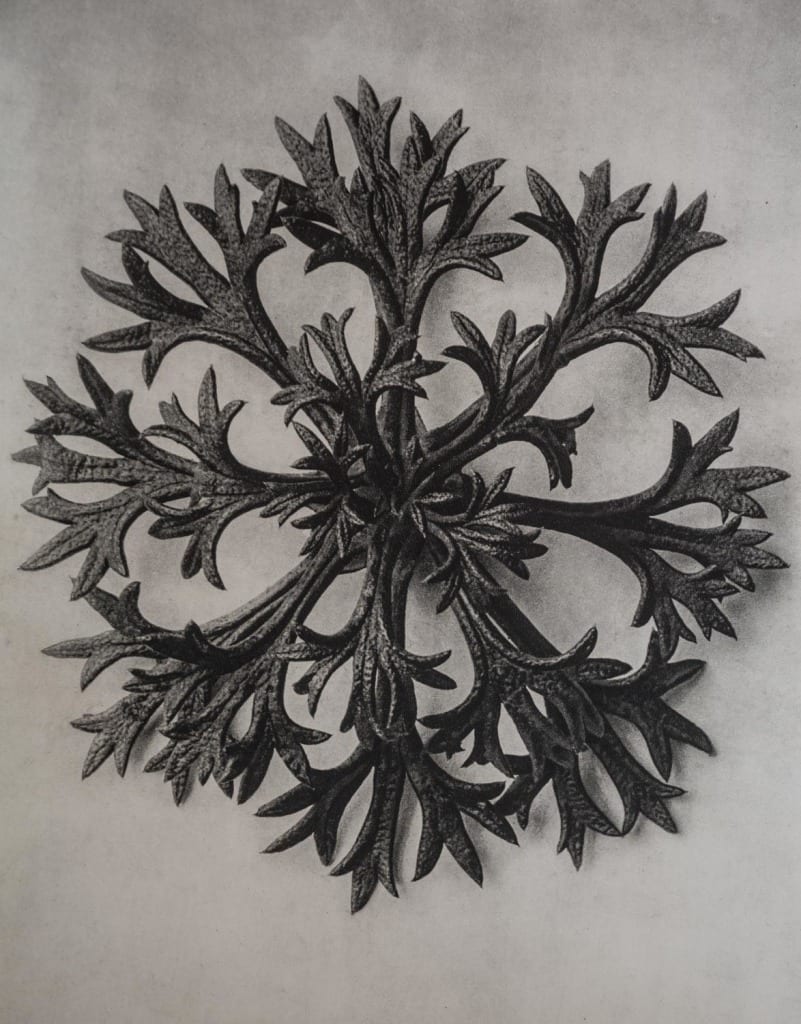

Whilst her images captured the abstract shapes and structures in the detailed outline of vegetal specimens, Karl Blossfeldt (1895 – 1932) was inspired by the sculptural, even architectural, shapes of plants. His extraordinary photographs, made with equipment he adapted at home, captured the detail of plant morphology, and were published in the celebrated monograph Art Forms in Nature (1928). Blossfeldt was working in the ambience of Art Nouveau whose sinuous curves were likewise derived from the aesthetic beauty and dynamic forms in the plant kingdom. In this spirit, we can appreciate a shared creative will that finds expression in both nature and in art.

A: What do you hope audiences take away from the show?

GB: I hope they might leave with a sense of wonder about the magical world of plants and the many artists and thinkers who have contemplated their mysteries through time.

The exhibition is currently closed. Discover it online here.

Image credits: Karl Blossfeldt, Plant Studies, Urformen der Kunst: Photographische Pflanzenbilder, 1928. Photograph, 31 × 24 cm. Public domain

1. Anna Atkins, Photographs of British Algae: Cyanotype Impressions, Volume I, Cyanotype, Public Domain,