In May 2000, a new chapter in cultural history opened on London’s South Bank. Tate Modern emerged from the cavernous remains of the Bankside Power Station, transforming an industrial relic into a space alive with possibility. Since opening 25 years ago, the gallery has welcomed over 100 million visitors. This milestone cements its status as the most visited modern and contemporary art museum in the world and one of the UK’s most significant cultural landmarks.

The building itself stood as a metaphor: monumental, stripped back, resolute. From the beginning, the vision was clear. Contemporary art would no longer be hidden behind closed doors or buried beneath the weight of traditional hierarchies. “This is the greatest museum of modern art in the world,” said Sir Nicholas Serota at the opening. “It has given Britain a presence in the international art scene that we lacked.” For Serota, art was never decorative. “Art and culture make life worth living,” he stated in an address to the British Council. “They can surprise, inspire, challenge and disturb. They allow us to understand ourselves and others better.” These words helped define Tate Modern’s role as a space for reflection and critical engagement, where audiences could confront the world as it is – and imagine it as it might become.

From that moment onwards, Tate Modern began expanding the canon. The first exhibitions revealed an appetite for bold curatorial decisions and global perspectives. Century City in 2001 offered a new way of seeing modernity, exploring creativity through the lens of key cities like Lagos, Mumbai and Rio de Janeiro. This approach prioritised context over chronology, and plurality over purity.

In 2006, Albers and Moholy-Nagy: From the Bauhaus to the New World drew vital lines between early 20th century experimentation and the emergence of modern design in America. The show offered more than a survey; it was a study in migration, influence and reinvention. Through vibrant abstraction and visual discipline, it reminded audiences that innovation often travels in exile. Meanwhile the 2008 Duchamp, Man Ray, Picabia exhibition traced the radical collaborations and shared provocations of three key figures in Dada and Surrealism. The curatorial lens was intimate and incisive, revealing a web of influence that extended beyond stylistic revolution into questions of authorship, identity and play. It became one of the gallery’s most discussed shows, drawing wide attention for its energy and surprising tenderness.

In 2010, Exposed: Voyeurism, Surveillance and the Camera brought urgency to the contemporary relevance of photography. The show was unflinching. Through images that provoked, unsettled and interrogated power, it addressed the tension between public and private life – prefiguring a decade shaped by digital visibility. It marked a curatorial turn toward thematic boldness and socio-political critique. And in 2012, the launch of The Tanks introduced an entire section dedicated to live performance and moving image. No longer confined to walls, art moved into time, sound and space, asking viewers to become participants. Later, in 2016, the Georgia O’Keeffe retrospective challenged long-held interpretations of her work, replacing myth with insight. Through over 100 paintings, the show positioned her as a central figure in 20th century art.

The gallery’s 2017 exhibition Soul of a Nation: Art in the Age of Black Power shifted the cultural conversation. Through work by over 60 African American artists, it examined how creativity intersects with identity, protest and resilience. Audiences engaged deeply. The show attracted visitors from across generations and communities, leaving a lasting impression on the national dialogue. More recently, Yayoi Kusama: Infinity Mirror Rooms in 2023 brought immersive art to a new level. Visitors waited for hours, drawn not just by spectacle but by the emotional resonance of Kusama’s vision. Her mirrored environments offered quiet, introspective spaces where light and repetition created a sense of boundless experience. These landmark exhibitions reflect the breadth of Tate Modern’s programme: rigorously researched, internationally minded, emotionally charged. The gallery has consistently championed diverse voices, interdisciplinary practice, and urgent themes. It has redefined what an art institution can offer in a fast-moving world.

Over the past 25 years, Tate Modern has also transformed access to culture. The permanent collection is free. Millions have entered the space without a ticket, discovering works by Louise Bourgeois, Ai Weiwei, Agnes Martin and Zanele Muholi. School groups, families, first-time visitors and seasoned collectors move through the same spaces, encountering art on their own terms. The gallery has created room for both quiet reflection and collective experience. In doing so, it has helped place the UK at the forefront of the global cultural scene. Artists, curators, and thinkers from around the world now look to London as a place where dialogue and experimentation thrive. Tate Modern, in many ways, stands at its centre.

As the gallery marks its 25th anniversary, the focus remains on forward movement. From 9 to 12 May 2025, a celebratory programme will fill the building with energy and encounter. Louise Bourgeois’s Maman, first installed in 2000, will return to the Turbine Hall, towering and tender, a reminder of the gallery’s origins. A new trail of 25 key works will guide visitors through the galleries. The selection includes Rothko’s Seagram Murals and Dorothea Tanning’s Eine Kleine Nachtmusik, alongside new commissions and contemporary interventions. Immersive installations by Nalini Malani and participatory works by Meschac Gaba will highlight how artists continue to challenge boundaries and reimagine the museum experience.

Two new free exhibitions deepen this commitment. A Year in Art: 2050 explores speculative futures, pairing early 20th-century visions with contemporary responses to climate, technology and transformation. Meanwhile, Gathering Ground reflects on the connections between ecology and community, bringing together artists who centre land, identity and care in their practices. Works by Outi Pieski, Edgar Calel and Carolina Caycedo offer grounded, poetic meditations on resilience. Later this year, the programme expands again. A major retrospective on Simone Leigh will honour one of the most influential sculptors of her generation. A comprehensive survey of Southeast Asian contemporary art will introduce new audiences to dynamic practices shaped by colonial histories, migration, and myth. Each show continues the gallery’s mission to amplify underrepresented narratives and provide space for new perspectives.

Tate Modern enters its second quarter-century with clarity and ambition. The gallery has built more than a legacy – it has established a living framework for what art can offer to society. It continues to grow as a site of connection, empathy and insight. At 25, the vision remains expansive, generous and bold.

Words: Anna Müller

Image credits:

1.Bruce Connor, Crossroads, 1975 © reserved. Tate.

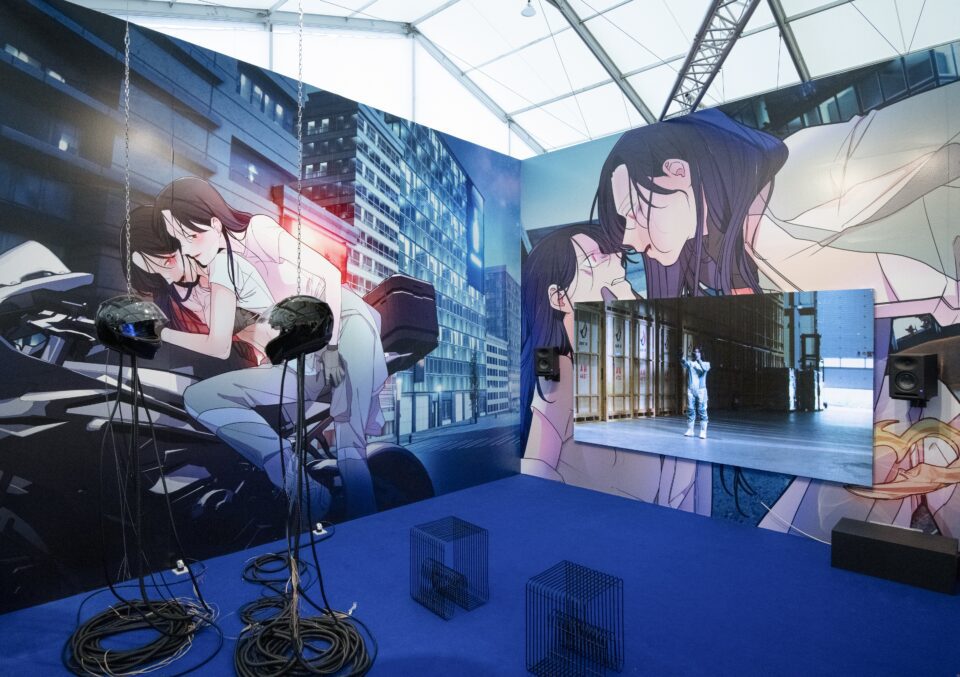

2.Ayoung Kim Delivery Dancer’s Sphere 2022 and Evening Peak Time is Back 2022 © the artist. Photo Tate.

3.Gauri Gill & Rajesh Vangad,The Eye in the Sky, 2014–16© reserved. Tate.

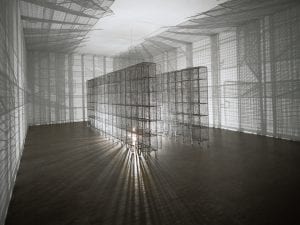

4.Nalini Malani, In Search of Vanished Blood 2012-20 © Nalani Malani. Installation photo, Nalini Malani, The rebellion of the Dead, Castello di Rivoli-Museo d’Arte.