A non-profit organisation takes charge of ocean health through major collaborations with artists and designers, promoting plastic-free lifestyles.

If the oceans die, so too does humanity. Our time on Earth would be over. Even so, there are more threats to marine and coastal health than at any other time in history. The pioneering biologist and explorer, Sylvia Earle, put it succinctly: “No ocean, no life. No blue, no green. No ocean, no us.” The seas are a vital part of the global ecosystem. A Greenpeace report, 30×30: A Blueprint For Ocean Protection (April 2019), produced as part of a year-long collaboration, spelled out exactly how this extinction would unfold: “High seas marine life drives the ocean’s biological pump, capturing carbon at the surface and storing it deep below – without this essential service, our atmosphere would contain 50% more carbon dioxide and the planet would be uninhabitably hot.”

And yet destruction marches on. Almost 80 per cent of the damage comes from land-based sources, according to UNESCO, which include anything from urban development and construction, discharge of nutrients and pesticides to mining and fisheries. This pollution has contributed to a number of low oxygen areas known as dead zones, where most marine life cannot survive, resulting in the collapse of ecosystems. There are now close to 500 dead zones, equalling in total the surface area of the United Kingdom.

Across the globe, governments are waking up to this disaster and are making commitments to help pull us back from the brink of collapse. Following the 30×30 report, Greenpeace called for countries to work together towards a UN Global Ocean Treaty by 2020 that would pave the way to protect at least 30% of the world’s oceans by 2030.

Outside the world of politics, what role does the creative community have in forcing change? Cyrill Gutsch, founder of non-profit organisation Parley for the Oceans, believes that culture has a “very big responsibility to the environmental cause.” For years, Gutsch co-ran a successful design firm but when he learned in 2012 about the realistic chance that the oceans would die within his lifetime, he felt an urgency to reinvent the company’s purpose and take action.

Now, Gutsch’s focus is addressing the major threats towards our oceans. “When starting Parley, we knew that we didn’t want to be a protest organisation that shames or blames the industry,” he says. “We wanted to move the responsibility to the creative population. To ourselves. Owning the problem means true leadership.” Parley’s central ethos is that the power for change lies in the hands of the consumer. The impetus to shape the consumer mindset lies in the hands of creatives. It is not only scientists and policy-makers but “artists, musicians, actors, filmmakers, fashion designers, journalists, architects, product inventors” who have the tools to mould the world. “We have learned that powerful ideas and visions can turn opponents into partners,” he adds.

In embarking on this venture, Gutsch was aware of the many threats to ocean survival; new pollution hazards compete with old ones and time is running out. Human overpopulation and overconsumption continues to increase and plastic waste has been choking the oceans since 1950s, according to research by Greenpeace, an estimated 12.7 million tonnes of plastic, a truck-load a minute, ends up in our oceans each year. Activist Greta Thunberg tweeted recently: “The problem of plastic pollution in the ocean is even worse than anyone feared. There’s actually more microplastic 1,000 feet down than there is in the Great Pacific Garbage Patch.” Meanwhile, the emerging threat posed by deep-sea mining “risks severe and potentially irreversible environmental harm.”

The factors contributing to ocean health are myriad, but so too are solutions. As such, Parley has collaborated with a range of brands and partnered with a number of high-profile designers to accelerate the impact of its global movement. Out of over 500 companies who expressed interest in working with the organisation, Parley’s first major partnership was with Adidas, who, in 2016, committed to using only recycled plastics in their products by 2024. Later that year, the brand unveiled its first products made from Parley’s Ocean Plastic.

This patented material – which is made from upcycled marine plastic waste recovered by Parley during clean-up operations in coastal areas of the Maldives – is designed to reduce the use of virgin plastic. Gutsch expands: “Plastic lost the trust. It became a symbol of the toxic age we created. Together with our partners we are driving what we call the ‘Material Revolution’, which will end the use of harmful and exploitative materials and production methods.”

It was first used in the form of new kits for football teams Bayern Munich and Real Madrid, as well as the first UltraBOOST Uncaged Parley running shoe. Three years on from the initial launch, Parley and Adidas have produced a range of items, including yoga and tennis clothes, all made from recycled yarn. The use of Parley’s Ocean Plastic is part of its “AIR strategy,” which means to “avoid, intercept and redesign.”

Environmental activism in fashion was once the reserve of few, like punk pioneer Vivienne Westwood, whose T-shirts emblazoned with the words “Climate Revolution” were just one of the ways she pushed green policy into the spotlight. Now, more clothing brands are following suit, such as Stella McCartney, who uses “regenerated” cashmere and only uses viscose that can be traced to “the forest it came from” to ensure that it is sustainably and responsibly managed.

Collaborations like Parley and Adidas show that putting the Earth’s health at the forefront can mean big business. Forbes magazine reported that if Adidas hit their target of selling five million pairs of Ocean Plastic shoes, the brand is set to make more than a billion dollars trying to solve one of the world’s biggest problems. “We knew that if we could convince Adidas to commit long term and become the blueprint of a new economy and the proof of concept of our strategy, we could change the whole industry,” says Gutsch.

Outside of fashion, Parley is tackling the ubiquitous and destructive plastic water bottle. A million are bought around the world every minute, and as their use soars, efforts to keep them from clogging the ocean are failing. Parley has teamed up with Soma to produce a reusable water bottle made from the equivalent of two plastic bottles and a proportion of every sale goes to support initiatives of the Parley Ocean Plastic Programme. “Plastic is a design flaw,” says Gutsch. “We cannot fix it overnight, but we can all take steps to create change. Shifting mindsets and behaviours is as important as creating new systems. We all have a role to play. This bottle is another reminder of that fact and the beginning of a new collaboration in the movement for solutions.”

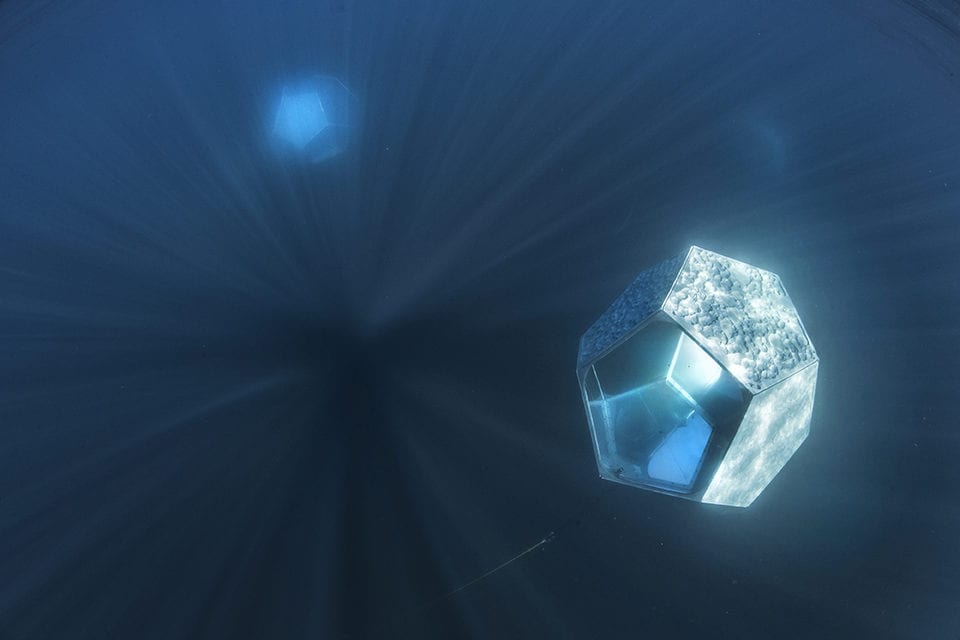

Parley has also harnessed the skills of fine artists. Doug Aitken (b. 1968) produced a large-scale installation called Underwater Pavilions in partnership with The Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles (MOCA) that consisted of three geometric sculptures made from carefully researched materials which work in harmony with the seascape. The eerie structures were moored to the ocean floor off the coast of southern California in 2016 and were mirrored to “reflect the underwater seascape and create a kaleidoscopic observatory for the viewer” and were large enough so that swimmers could move through them. It was an altogether huge feat.

The designs were intended to put “the local marine environment and the global challenges around ocean conversation in dialogue with the history of art” by calling on the viewer to participate in its protection. Aitken notes: “When we talk about the oceans and we look at the radical disruption we’ve created within the sea, we’re not quite aware yet how much it is going to affect us and our lives on land. The ramifications of that are immense. This is one thing which cannot be exaggerated.” The temporary underwater sculptures, which were hailed as a “new frontier for art”, are due to reopen to the public in a new location soon. The intent is to encourage a sense of wonder. “With such important artworks suddenly living underwater, there is no escape,” adds Gutsch. “One has to dive down to be part of the conversation. Once you are down there, you fall in love with this magic blue universe.”

Aitken also lent his talents to a new Parley project called Ocean Plastic Bags. Aitken, alongside Walton Ford, Jenny Holzer, Pipilotti Rist, Ed Ruscha, Julian Schnabel and Rosemarie Trockel, created designs for a reusable tote bag made from roughly five plastic bottles collected from remote islands by the Parley team. The sale of each bag funds the clean-up of 20 pounds of marine plastic waste. The concept merges creativity with design and, for Gutsch, shows the power that artists have to create a strong message. “When exposing yourself to an artist, you enter such an encounter with an open mind. You want to be provoked, even shocked.”

However, environmental activism and awareness through good design is not only the reserve of Parley. As part of Cooper Hewitt’s sixth Design Triennial, a new exhibition on view at the Cube Design Museum in the Netherlands until 2020 celebrates the history of creative collaboration with nature. The work of 62 international design teams is presented, showing partnerships involving scientists, engineers, philosophers and advocates for social and environmental justice. It highlights designers’ strategies to “understand, remediate, simulate, salvage, nurture, augment and facilitate.”

“Nature offers a timely look into how designers are tackling the environmental and social challenges confronting humanity,” Caroline Baumann, Director of Cooper Hewitt, states. “This is not just an exhibition, this triennial is a call to action.” Highlights include an algae-based plastic jacket designed by Charlotte McCurdy that helps absorb carbon and the display of a new material named Lithoplast, which was made by Shahar Livne by mining petroleum-based plastics.

The work that Parley and other creative organisations and individuals are doing makes it clear that the design world is an essential part of the solution to ecological collapse. The once-rigid division between disciplines – art, science, fashion – seems arbitrary in a world where the complex issues of the day need, more than ever, a collaborative approach to solutions. As Thunberg attests: “It is still not too late to act. It will take a far-reaching vision, it will take courage, it will take fierce determination to act now, to lay the foundations where we may not know all the details about how to shape the ceiling. In other words, it will take cathedral thinking.”

Alexandra Genova