Over the last four years, Nxt Museum in Amsterdam has established itself as a destination for new media art, spotlighting those working at the intersection of art, technology, science and sound. Amongst the exciting artists who have come through its doors are Heleen Blanken, Jacolby Satterwhite, Julius Horsthuis, Lu Yang, Marshmallow Laser Feast and Random International. Still Processing, the latest show, takes a deep dive into how we interpret the world around us. It asks: how does technology shape and manipulate images? And how does the brain process movement, light and sound to construct meaning? These are huge questions, and the seven exhibiting artists – Balfua, Boris Acket, Children of the Light, Gabey Tjon a Tham, Geoffrey Lillemon, Lumus Instruments and Rosa Menkman – come at them from different angles.

Menkman (b. 1983), a Dutch artist, researcher and educator, is at the heart of the show. A self-described “media archaeologist from the future,” she digs into the machinations of image processing – the technique of using computers to improve, modify or analyse digital images. Menkman traces phases of image development: the transition from analogue to digital, the rise of photo-sharing, computer-generated imagery and JPEG compression. Right now, when generative AI is often in the headlines, her work couldn’t be more relevant. Still Processing takes influence from various moments of human and natural history: from 19th century novellas to 1980s holography and swarms of birds and insects. Each piece offers a different sensory experience, manipulating light and sound to have an impact on the viewer. Aesthetica sat down to discuss the show with Curator, Bogomir Doringer.

A: What was your starting point for Still Processing? Where did the idea come from, and did the concept lead the selection, or did the artworks shape the final theme?

BD: The idea was to showcase artists whose practice developed on the fringe – in experimental spaces, art festivals and clubs – who have since entered more academic or traditional art spaces. These are creatives whose practice has evolved into a craft that is uniquely theirs. The question for me was: what is craft when we think about new media, kinetic sculptures or software? How can we display works on a screen, but also dissolve the screen and give precedence to what happens in our minds? Still Processing is about the way we are wired and how we cognitively process audiovisual inputs. The title came after a series of long discussions, and I think it’s perfect for the times in which we live. We are still processing – there’s so much happening and there is an overload of inputs. In Nxt Museum, there are many different spaces, with transition rooms in-between them. The architectural layout of the museum also directed the way exhibition developed.

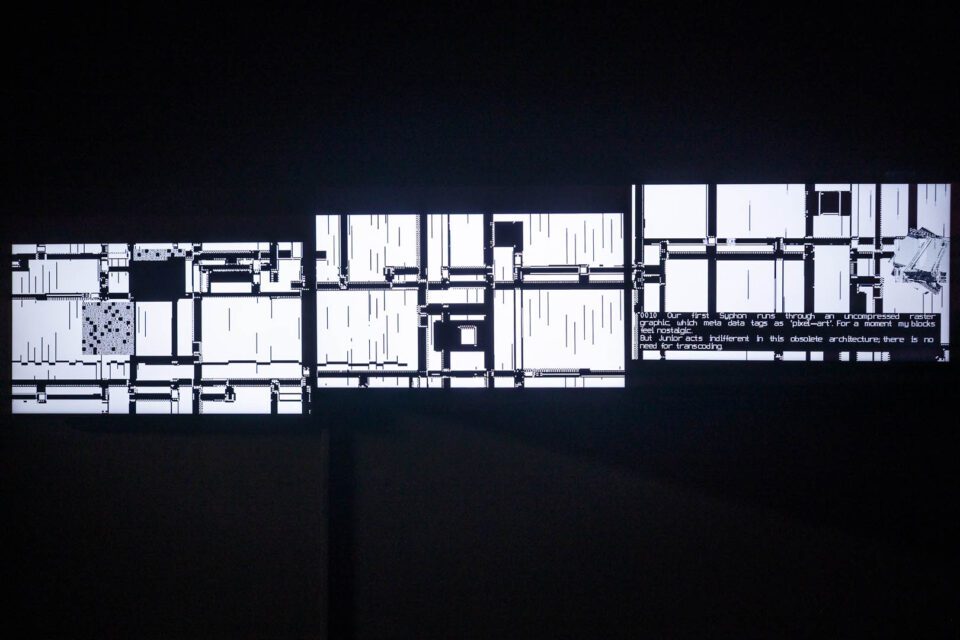

A: The research and work of Rosa Menkman seems to be central to the show. Why did you choose to spotlight her?

BD: It was very important to give a big stake to Rosa Menkman, an artist who has followed image development for decades. Her projects helped shape the narrative and the flow of the exhibition – in a way, she’s presenting a show inside of a show. Each of her spaces addresses a certain phase of image-making, whether it’s .jpeg, AI generated images or bias in training data. What’s interesting about her work is its sense of storytelling. Something complex and technical becomes philosophical, existential – almost like a love story. You can follow her very technical research from an angle of dramaturgy. It speaks to the heart and mind – this was important for communicating complex processes to a broader audience.

A: It feels like a number of the artworks in Still Processing are underpinned by key historical, literary or scientific moments. Can you give an example of this in action?

BD: In 2019, Katie Bouman made a scientific breakthrough that allowed us to visualise the unseeable: the first-ever image of a black hole processed by a new algorithm. I was fascinated when Bouman’s image was created, because it really shifted understandings of photography. Multiple different satellites had to come together to compose that one image. It reminds us that we don’t have a final render of our reality, and that what we see as “truth” is still processing, as new developments come along. Children of the Light, the Amsterdam-based artist duo of Christopher Gabriel and Arnout Hulskamp, found inspiration in this now-viral visual.

A: What was the result? How did they turn the image into installation, and what is the experience of viewing it like?

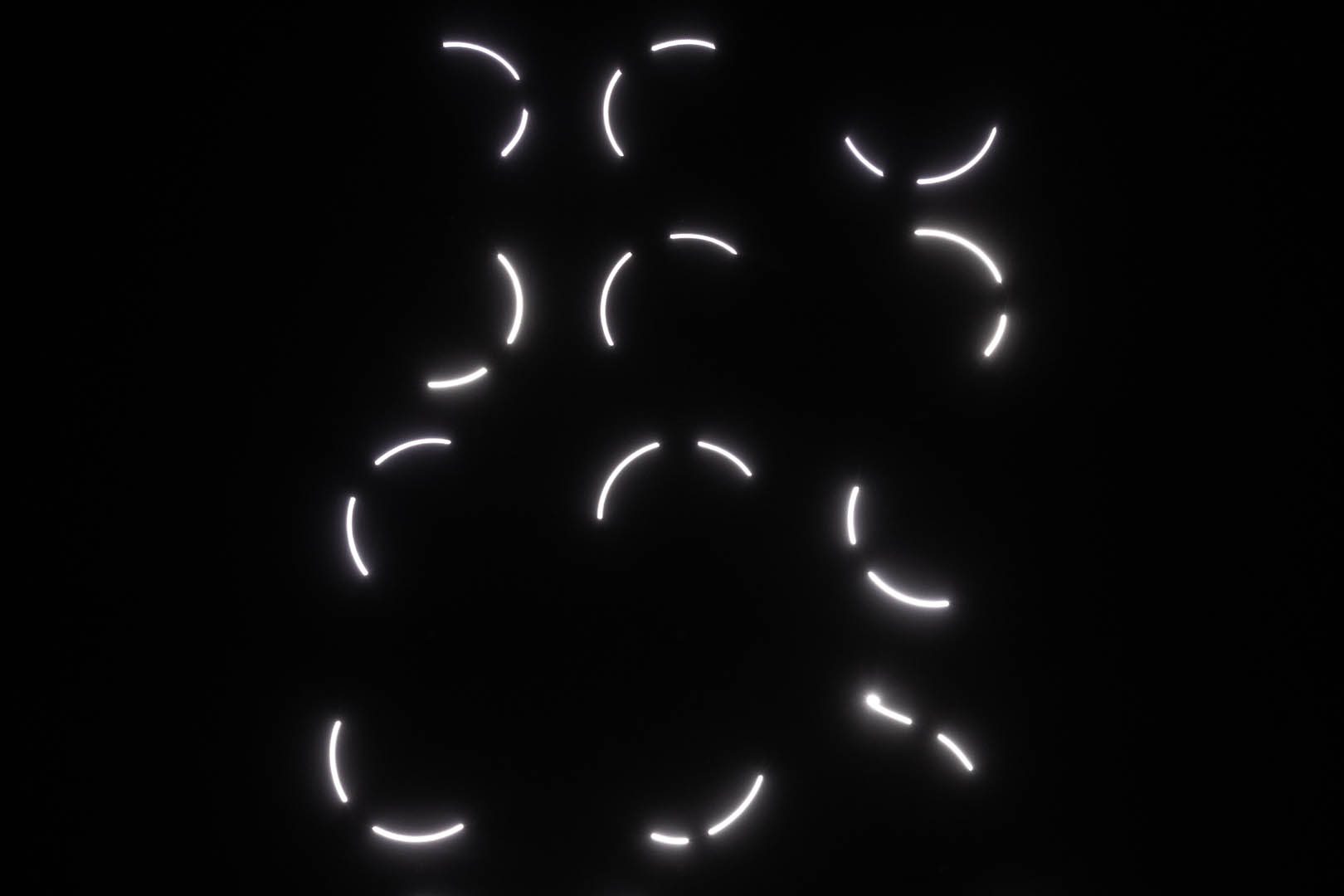

BD: ALL-TOGETHER-NOW is a line of five identical rings, exhibited in a very long corridor. They are choreographed to move until they reach moments of synchronicity. Whilst you’re standing there, you eventually see a deep, dark space emerge. The object is moving so slowly that it also causes you to change pace. It confuses your perception of space; the only way to reach the exit is once the object gets out of your way. Sometimes you’re not sure if it is hollow, or if you’re looking at a mirror. The tone and temperature of the light in the work shifts over time, from amber to pure white, creating an illusion of seeing the spectrum of colours. It’s interesting how our bodies and minds process that colour, because you can feel the warmth of an object that doesn’t have heat. ALL-TOGETHER-NOW is an absolutely moving artwork.

A: Why does it have such a profound impact on people?

BD: Rings, especially those that glow, are present in religious iconography and have been part of our shared human history for such a long time. They are iconic and really seem to do something to our brains and bodies. On paper, you can’t imagine what kind of physical impact this installation will have, and how it will define the space. But it creates a moment of togetherness. Gathering around these large suspended rings becomes almost ceremonial. Children of the Light has exhibited in churches, on the stage, in clubs. No matter where it is, they manage to gather a group together.

A: Duration, by Boris Acket, is another one of the show’s expansive sensory artworks. How does it look and feel?

BD: Duration is a very large-scale installation, and it asks a very big question: how do we experience time? It’s a huge responsive grid, with pillars, LED screens and a custom-built echo system that deconstructs singular audio inputs into patterns and interplays them with light. The sounds in the space were collected from field trips that Acket made. It might feel very electronic, but the source material actually comes from drops of water in caves, or the ocean. What’s fascinating is that you’re inside of an extremely heavily technological space, but it has a comforting feeling – like a kind of digital forest. During the opening, we had live instruments playing and the experience could have lasted for hours – the audience was captivated. Over the course of the exhibition’s run, Duration will be activated by various different music collectives and visual artists through our residency programme.

A: Debates around digital art often hinge on the idea of machines replacing authentic input. How do you strike a balance between high-tech and human at Nxt Museum?

BD: When I’m curating, and in my own artistic practice, it all comes down to the conscious and unconscious ways we, as humans, both collectively and individually, navigate through times of change – sometimes very radical ones, like wars or conflicts. These artworks are not always about demonstrating how technology works, but instead ask: how can we evoke certain feelings, sensations and meaning whilst using it? Or, can we create entirely new tools for artistic expression? For Nxt Museum, it’s important for us to retain that human aspect and question the evolution of technology. I’m not sure if we always achieve that, but I do think that the dramaturgy of the whole exhibition offers some kind of solutions to machine dominance. Right now, with Facebook, Amazon and Elon Musk in the White House, we’re observing that people are resisting technological developments, like AI, because they are related to right wing political agendas.

A: What have you discovered during the process of putting this show together? Has anything challenged you?

BD: I’ve discovered there is a big gap in understanding how technology works, even though it’s such a big part of our lives. Huge corporations, and the way that they develop their products, have allowed a kind of myth to proliferate. In 2025, we still have same questions as 20 years ago. And it’s not a generational gap, it is just that we are kept in that mode of not knowing. We depend on technology that is mostly based in one place, and we are no longer able to open our devices to see how they work. The iPhone, for example, has become a kind of black box. That kind of thing leads to speculations or misleading conspiracy theories. We need to investigate alternative tools – like where our email is based, for example.

A: Are there any trends or developments in the art and technology space that you’re particularly excited about?

BD: One of the main topics that has interested me over the years is the ritual of dancing and masking in post-9/11 society, and how we feel about technology when it’s used for surveillance. Through new media art, there has been a revival and reinvention of theatre and dance. It’s interesting how these environments can activate the body and encourage people to re-connect, both with themselves and one another.

A: How have audiences responded to Still Processing? How does it compare to other shows you have curated?

BD: It feels like the exhibition, and its title, have really resonated with people. It’s a show that questions what you know – or don’t know – about yourself, and how the mind works. I’ve curated four exhibitions at Nxt Museum, including UFO – Unidentified Fluid Other (2022 – 2023), which explored who we are becoming in virtual worlds. Still Processing leaves a lot of space for interpretation. Every room is so different. The artworks are on screen, but they really do break and deconstruct that resolution. This is may be our best show to date.

Still Processing Nxt Museum, Amsterdam Until 5 October

Words: Eleanor Sutherland

Image credits:

1. Boris Acket, Duration, (2025). Light installation, co-produced by Studio Raito, Bob Roijen, Corey Schneider with music by Boris Acket. Photo: Maarten Nauw.

2. Children of the Light, ALL-TOGETHERNOW, (2025). Installation, with sound by Sébastien Robert, engineering by Luuk Meints, electronics by Diederik Schoorl. Photo: Maarten Nauw.

3. Rosa Menkman, DCT:SYPHONING: The 1000000th (64th) interval, (2015-2017). Photo: Maarten Nauw.

4. Children of the Light, ALL-TOGETHER-NOW, (2025). Installation, with sound by Sébastien

Robert, engineering by Luuk Meints, electronics by Diederik Schoorl. Photo: Maarten Nauw

5. Gabey Tjon a Tham, Red Horizon, (2014). Light installation, co-produced by TodaysArt & Museum of Transitory Arts (MOTA), supported by Stroom Den Haag and Creative Industries Fund NL, Software development: Marcus Graf, Mechanical engineering support: Bram Vreven. Photo: Maarten Nauw.