In the 1950s and 1960s, economic and colonial privileges attracted thousands of Portuguese migrants to Mozambique. They carried with them white, middle-class habits and comforts: garden parties on trimmed front lawns; family days at the beach; Sunday dinners; pleasantly quaint – but gated – weekend cottages. Decades later, the photographs, official documents, passport papers and personal letters that had accumulated over the course of these lives found their way to a flea market in modern-day Lisbon. That is where Délio Jasse, a Lisbon-based Angolan artist, found them a few years ago.

Jasse’s new and previously unseen body of work comes together in this solo exhibition, The Lost Chapter: Nampula, 1963 at London’s Tiwani Contemporary . Having moved to Portugal at the age of 18, the artist known for his experimental photographic printing work, which creatively blurs the lines between found object, analogue photography, printing and archival work. He explores cyanotype, platinum and early printing processes such as Van Dyke Brown, as well as developing his own printing techniques. Recently exhibiting at the 12th Dakar Biennale (2016) and the 56th Venice Biennale (2015), Jasse turns his confident hand to the fragments of an adopted colonial past.

Starting with the Nampula materials he found in the flea market, Jasse has pieced together aspects of a family’s narrative by cross-referencing private photos against the official paperwork, including bank stamps, government letters and passport documentation. What emerges is a series that bear the marks of history, but present themselves as dreamlike and evocative. Perhaps even the artist – who, in a conversation with Stefano Rabolli Pansera at the gallery on 12 November preferred to call them documents – at times glosses over these latter qualities in these works.

The A Minha Casa series (2016), for example, consists of two soft-blue cyanotype prints that evoke two simultaneous realities. The top halves are Nampula scenes, often a home’s exterior; the bottom halves, an intimate facial close-up of a stranger. A deliberate association? An invoking of a memory? The images are from the same decade and place in Mozambique, but they are unrelated finds from Jasse’s flea market trips. Yet this fictionalising act of marrying the two is the creation of a storyline, a narrative for these ghosts of Portugal’s colonial past.

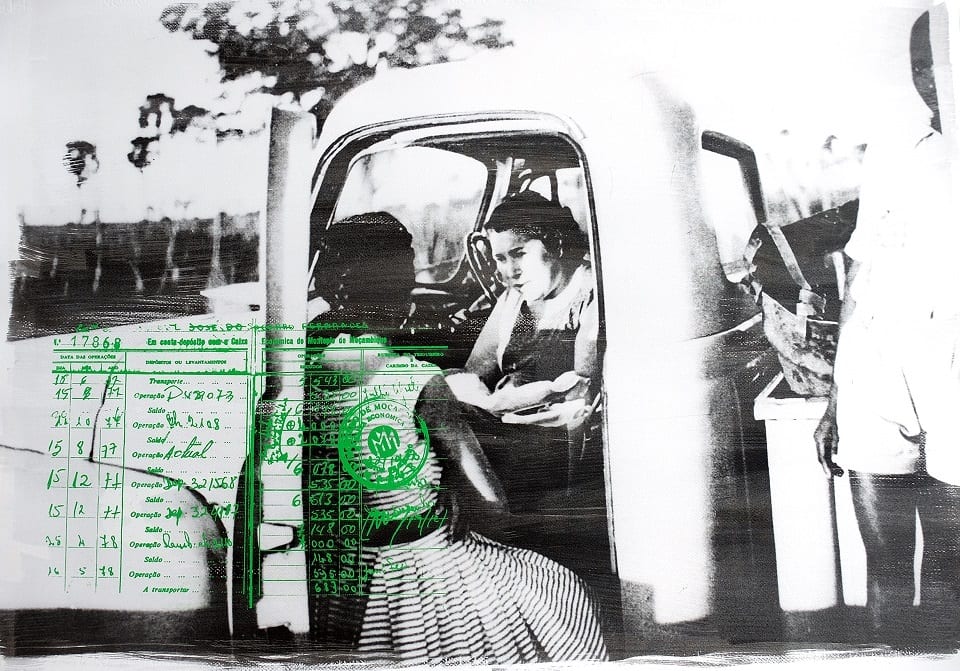

With other found photos, Jasse chooses to transform the original black-and-white image with screen-printed stamps he has transferred from official documents that accompanied the boxes. These bright, neon government seals and scribbled signatures encroach upon the lighthearted, intimate image of a carefree family, injecting a touch of the political and the bureaucratic. How many black Mozambicans would have lacked the freedom of movement and the certainty of access that these stamps and seals could provide, easily, to these strangers arriving as masters?

Indeed, where are the locals in all of these photos – many of which depict public spaces? Didn’t these Portuguese families mingle with – or at least employ – black Mozambicans? The absence of Nampula’s native residents and their culture is telling. The Portuguese families could be in any seaside city with a sunny clime. Reconstructing family archives, the wider historical and political narratives of Portuguese colonialism begin to overshadow the personal, and raise questions on both the period and its legacy on Mozambique today. Questions which remain unanswered here, but presented to us with originality and a thought provoking multi-focality.

Collage and found objects come together as a new hybrid medium that can communicate how multiple histories overlap, and take them out of the shadows to give them a new audience. If anything, Jasse here has both the material and a conceptual thread strong enough to push these pieces to work harder, delving further into the themes they already suggest: identity, official-versus-personal histories, native absence and postcolonial memory. As it stands, it leaves much to the viewer, though it has the substance to justify a little more ambition.

Sarah Jilani

Délio Jasse, The Lost Chapter: Nampula, 1963 runs until 17 December at Tiwani Contemporary, London. Find out more: www.tiwani.co.uk

Credits:

1. Délio Jasse The Lost Chapter: Nampula, (1963). Courtesy of the artist and Tiwani Contemporary.