“The camera has often been a dire instrument … in most parts of the dispossessed, the camera arrives as part of the colonial paraphernalia, together with the gun and the bible.” Zimbabwean novelist Yvonne Vera’s powerful observation casts the history of photography is a damning light. The invention of the daguerreotype in 1839 was a moment of human ingenuity and progress, but for many living under colonial rule, it was yet another tool for those in control to exert their power. Photography later became a means of self-expression, documentation and resistance for many living in colonised nations, but its early history was largely wielded by those in authority. In British-controlled India, for example, the camera was often used to reinforce imperial ideologies, which viewed the landscape as something to be conquered and owned. This perspective proves Vera’s perspective and illustrates how the same experience was echoed around the world. Crossings: Photography from the Indian Subcontinent, a new exhibition at Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam, presents 19thcentury British colonial images in dialogue with contemporary work by French-Sri Lankan photographer Vasantha Yogananthan. The show opens up new ways of viewing historical collections, offering much needed context to colonial imagery. We spoke to Curator Hans Rooseboom about how the show reconsiders traditional understandings of lens-based art.

A: Tell us about how this exhibition came about.

HR: Two years ago, I had a talk with Nitish Soundalgekar, a young Indian art historian who had previously worked for Rijksmuseum. He suggested that we modernise our collection of photographs from India. These had been catalogued decades ago, which meant the descriptions had begun to sound dated and could be improved and expanded. It’s a large and important part of the photography collection – it totals 1,200 photographs – so I thought this was a splendid idea. After a while, we had the thought of devoting a presentation in the Rijksmuseum Photo Gallery to this theme, which is how Crossings originated.

A: Crossings weaves together colonial documentation and contemporary storytelling. What was the strategy behind bringing these two periods together?

HR: The Rijksmuseum’s collection from the Indian subcontinent consists almost exclusively of photographs from the 19th century. Since that time, both photography and the region itself – becoming independent from British colonial rule in 1947 – have evolved massively since then, so it made no sense for this exhibition to stop at 1900. We therefore decided to add works by a contemporary photographer from that region and my fellow curator, Hinde Haest, proposed Vasantha Yogananthan.

A: The exhibition spans multiple regions – India, Nepal, Sri Lanka, Bhutan and more. How did you approach curating such a geographically and culturally diverse narrative?

HR: The majority of photographs in this sub-collection were made in what is now India. But they were made prior to the creation of modern-day states like India and Pakistan and were part of the former British Empire in Asia. That means that their origin now spans various modern nations. Soundalgekar and I decided to limit ourselves to the areas that fell within the influence of the Empire.

A: Yogananthan’s series, A Myth of Two Souls, takes the Ramayana – a foundational epic in Hinduism – and reimagines it through photography. What drew you to this particular body of work for exhibition?

HR: Apart from the intrinsic quality of the work of Yogananthan, it was the fact that he travelled for some years through the region – like Samuel Bourne did in the 1860s – that attracted us. By focusing on the Ramayana, he sheds a new light on ancient locations and stories. He documents the presence of the Ramayana epic in modern daily life and how this traditional story is still being retold and rewritten. It is a highly personal body of work that is the outcome of an exploration of his Sri Lankan heritage.

A: Yogananthan is part of a growing wave of photographers rethinking postcolonial identity. How does his work speak to or resist the legacy of colonial visual storytelling?

HR: We deliberately wanted to include a modern voice and vision from someone with roots in the area – Yogananthan has a Sri Lankan father and a French mother and was raised in France. In contrast to the large majority of photographs from the 19th century, it is a vision from within. The selection Yogananthan made for this show is therefore an addition to the usual western way of depicting the landscapes, cityscapes, architecture and people from a “far-away exotic country.”

A: How do you balance and interpret both the subjective, colonial viewpoint of well-established photographers like Linnaeus Tripe and Samuel Bourne, whilst also acknowledging their historical significance?

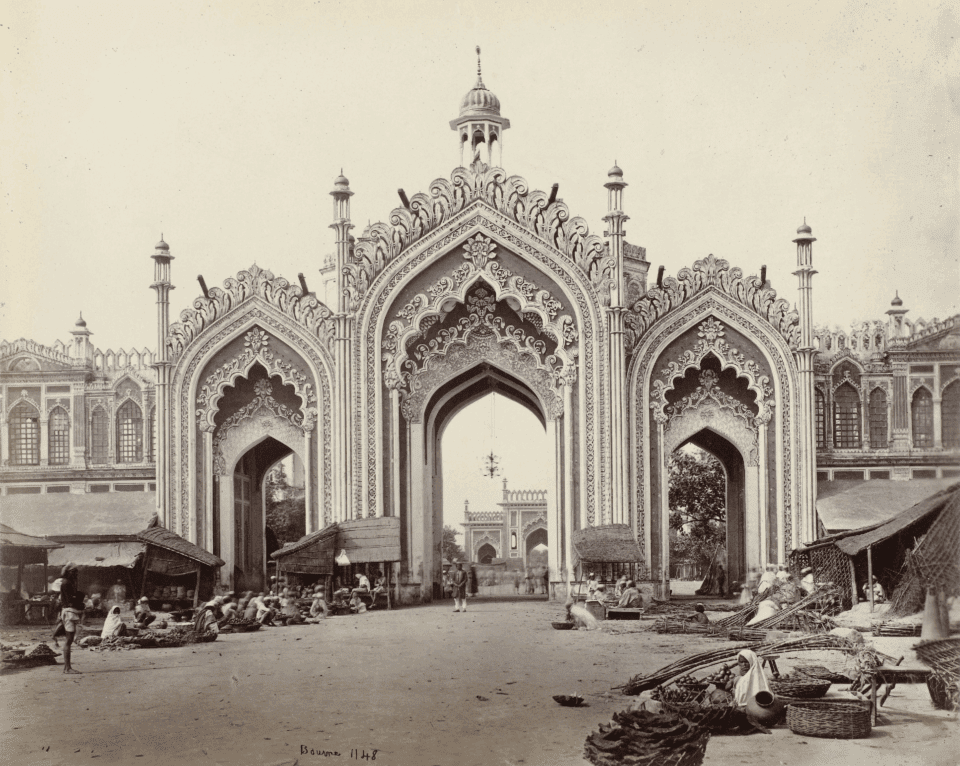

HR: All 19th century photographs are accompanied by a label text, disclosing the context in which these works were made. We did not want to point fingers, but we could not ignore the fact that most, if not all, photographers active in the 19th century did what their clients wanted. In this case, it was the British colonial rulers and the British audience of individual buyers. They therefore confirmed the usual way of looking at foreign nations. While Bourne ran his own commercial studio and sold his photographs to a large audience of westerners, Tripe and others were commissioned by various British institutions to document temples and other pieces of art and architecture.

A: In a time when cultural institutions are rethinking how they hold and present historic pieces, how does this exhibition speak to broader conversations around decolonising museum spaces?

HR: Apart from the wish to share the richness of our collection with the museum visitors – a natural thing for a curator who loves photography – I think the major task we set ourselves in this show was to do justice to the historic context in which the photographs were made.

A: What do you hope audiences take away from visiting the show?

HR: An important driving force behind the exhibitions in our Photo Gallery is to display the richness and importance of our photography. It is a well-kept secret that the Rijksmuseum has a large photography selection. The museum is known for its collection of 17th century paintings, but there is more to explore.

Crossings. Photography from the Indian Subcontinent is at Rijksmuseum until 12 October: rijksmuseum.nl

Words: Emma Jacob

Image Credits:

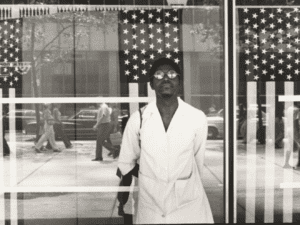

1&5. Vasantha Yogananthan, Longing For Love, Danushkodi, India, 2018 Archival inkjet print. From the series A Myth of Two Souls (2013-2021). On loan from the artist.

2. Samuel Bourne, View from the Manirang Pass, showing a succession of snowy summits, Himachal Pradesh, India, 1864-1866. Rijksmuseum.

3. Vasantha Yogananthan, Demigod, Kulasekharapatnam, Tamil Nadu, India, 2019. Archival Inkjet print from the digitalisation of silver negatives. On loan from the artist.

4. Samuel Bourne, Husainabad gate in Lucknow, Uttar Pradesh, India, 1864-1866. Rijksmuseum.