France-based contemporary artist Salomé-Charlotte Camors questions our individual responsibility for environmental and social issues. Undertaking extensive research, she then utilises conceptual photography to go beyond an image – to crystallise the interactions constitutive of our identity and conception of reality.

A: Your practice is both research- and photography-based. How do you combine these two processes?

SC: I use photography as a medium and not as an end by itself. It’s just a tool that I combine with other materials or forms of expression to achieve a specific goal. That’s maybe why I consider myself more a conceptual artist than a photographer. Research is fundamental in my work – probably more than technics because the meaning is the only thing that really matters to me and I have to transcribe this meaning in my work in an understandable way for the viewer.

The combination is done naturally. Since its invention by Louis Daguerre, photography has replaced painting as the main mode of representation of the world and has become a valuable tool for research documentation and transmission of knowledge. However, even if the images are part of our representation of the real world, even if they influence it, they’re not the real world. Our massive exposure to images, particularly through the media, tends to create a distance and a disengagement of individuals. And this is the core of my work: to question the viewer about their responsibilities as an individual.

A: Your images consider our individual responsibility for social and environmental issues. Why is this important for you, both personally and professionally?

SC: This question could lead to a very long philosophical dissertation. But if I had to put it simply, there is a saying in France: “Les choses sont ce qu’elles sont” which means: “Things are what they are.” This illustrates well the disengagement of responsibilities I’ve mentioned. But things are not “what they are”, they are “what we do” and “how we deal with them.”

There is an immeasurable amount of problems in our society. Each year, we consume more resources than our planet can produce and many species are endangered. It’s often almost easier to find a plastic bag than an animal in nature. Even if we don’t consider our impact on the environment, our human civilisation is deeply unequal, not only economically, but also because of harassment due to sexual orientation, gender, religion and skin colour. None of these issues are natural – they only exist because our species created it.

This induces a deep malaise, and to avoid facing these problems we’re sacrificing our minds to multinationals in exchange for a shot of the ephemeral happiness promised by capitalism. We’re increasingly outsourcing our cognitive functions, freeing brain time available for advertisements, entertainment and mass consumption.

As an artist, I think I have to bring my modest contribution to a better world, and this passes by exchange and dialogue. If my work can make people curious and give them the willingness to embrace difference and make them more self-conscious, I would consider it a success. I don’t believe in any kind of absolutes, as I’m not a spiritual person, but to live, humans need to find or create meaning. I’m convinced that knowledge, doubt and conscience make violence go backwards and increase our existence intensity, so it’s also personally important for me to contribute to this awareness – that’s the meaning that I wish to give to my existence.

A: In issue 87 of Aesthetica, The Spider in my Mind was one of the photographs displayed. This piece has been awarded an honourable mention in the 13th Julia Margaret Cameron Award – congratulations. What is the story and process behind the piece?

SC: Thank you. The Spider in my Mind, like the whole Paquare series was realised during a volunteer environmental mission to protect sea turtles and clean beaches in Costa Rica. It was an unforgettable experience, especially because we lived in very hard conditions without electricity or hot water. Hot water can seems unnecessary in Costa Rica. But after a four-hour night patrol under the cold season’s torrential rains, wind and the ocean’s waves, heat is not a luxury. I still can remember the cold, deep inside my bones and the strange feeling to be cut from everything I’ve known.

When I arrived I didn’t know what would be the final shape of my work; it was the limit felt and the immanency of environmental deterioration that conditioned the beginning of this project. Our intervention was useful but first of all I realised that it won’t be enough to reverse the destruction induced by mindless human activity. The only way would be to change our consumption habits – that’s what leads me to search for a way to operate a connection between viewer and nature by a transfer of affect from the work to nature.

That’s how I decided to work with raw iron, which presents the particularity of being sensitive to oxidation. Thus, without special attention and care, the work will be slowly destroyed. This process acts has a mirror with nature. There is no wasted land in my series, no mountains of plastic (although I spent days collecting plastic bottles on the beach), there is only nature in all its beauty. I didn’t want to show the damage we do, as s a lot of photographers do it much better than me. What I want to show are the very few preserved areas which we are going to lose if we don’t do anything.

As we discussed, the exponential profusion of images disempowers us. As an example, we see the famous images of the anaemic polar bear and it provokes sadness, but instead of changing habits, it’s easier to convince ourselves that we can’t do anything, that it’s too late, that industry is the only one responsible or that there are too many things to change. It could be a comfortable deal with our consciousness, but it also may keeps oneself apart from a real existence.

Thus, through my work I intend to crystalise the interactions which constitute our reality. In this case, the passivity of the viewer towards my work will have the same result as passivity toward nature. As a more short-term oriented enjoyment object, I hope that my work will be able to spark actions and thus break this routine of passive reception.

A: The Spider in my Mind is part of the Paquare series – why did you choose Costa Rica as the location for the project?

SC: I can’t say that I really chose Costa Rica for the project, as it was more of an opportunity. A famous NGO was recruiting for this mission on Facebook and I thought that it would be a perfect occasion to be at the core of operations.

Usually, my work method is pretty simple. I first chose a subject more or less broad that will be refined over time. My work being engaging, I always chose subjects related to environmental or social issues. Then, I try to extricate global interactions between the environment and individuals to find how to transpose them in an artistic dimension through the interaction between author, works and viewer. I have little control over this part, as it’s probably the part of mystery in the artist’s brain. This is how I decided to experiment with photographs on different materials, with different chemistries or staged in interactive installations.

Afterwards, comes the research phase. I have a master’s degree in management, so I’m familiar with data analysis and documentation. During this time I read a lot, from a lot of different disciplines, to gather as much information as possible on my subject. I also try to plan the realisation part. This work could be related to a period of gestation. Research doesn’t really have an end, even during realisation period, so encounter and experience are contributing to their enrichment.

Finally, I begin to harvest my photographic material and work on the realisation. It doesn’t always happens like this but generally it’s what you have behind all of my works. As you can see, conceptualisation and reflexivity are the most important parts. But for Paquare, the process was reversed: it was the experience that created the necessity to make research and then produce the work.

A: To what extent does a physical location inspire your work? Is the creation of your work driven by places in which you can observe or participate in environmental and social issues?

SC: I don’t have a particular method to choose my places of work. I try to make myself available to opportunities as much as possible. Multiplying experiences is probably the best way to enrich our representation of the world and our conception of reality, so I have to seek every opportunity to get out of my comfort zone.

When I work on environmental issues, there is clearly a part of performance in my work; I change roles by giving up the basic extensions of an average European citizen (phones, air conditioning, electricity and hot water) and the absence of these filters is the best way to connect emotionally to the place.

For sure, not being a mere observer also helps, so to participate in concrete actions and to immerse oneself in the local life allows us to enrich our understanding of a situation.

A: You participated in the Artists in the Arctic Spring 2019 residency, off the coast of Greenland. How did learn about the residency and what drew you to the idea of becoming involved?

SC: When I was in for Costa Rica, it was an opportunity. I created Paquare in 2016, and among all my productions this series received a particularly good welcome from the public and professionals. Thus, I wanted to give it a sequel and I had begun to search for more volunteering programmes in endangered environments. At the same time, a friend sent me a link to an art residency website, and it was obvious that I had to go there.

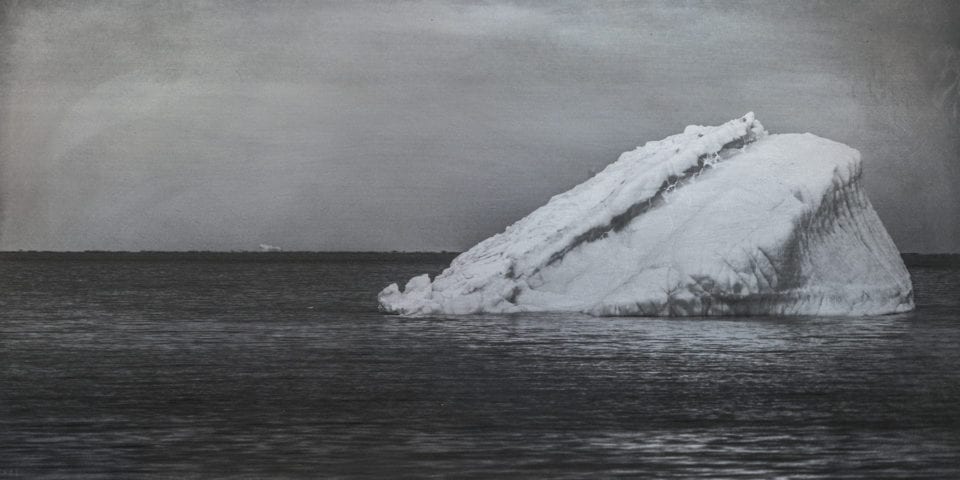

Arctic glaciers, as the biggest reserve of clear water and thermic regulators due to their high levels of albedo, are an emblematic region when we talk about human impact on nature. I sent an application for the 2018 edition, presenting the work I had done with Paquare and my desire to pursue this work over the Artic Circle. I was not part of the selected artists but they told me that I’d be part of a future edition, and that’s what happened.

A: What preparation did you do as an artist in advance of the residency?

SC: The preparation time was very short. Philippe, the president of the association called me in December to invite me to be part of the 2019 edition. I had a lot of work and travels planned but I felt that I couldn’t decline. Fortunately, I knew already exactly what I wanted to do: harvest photographic material to produce a sequel to Paquare and learn about local issues through contact with inhabitants. It didn’t require a lot of preparation: I borrowed some mountain clothes, checked my photographic equipment and spent some nights reading about women in history who explored the polar regions. I felt like I was about to live something incredible, and I was right.

A: Regarding the ship, Manguier, what was it like to live and work there? Do you think that your childhood experiences of living in different environments helped you?

SC: It was incredible. We were seven people on board: four artists, one guest, our Captain and the Vice Captain. Seven unknown people trapped for one month in a narrow space. It was an extraordinary human experience full of emotions.

What surprised me the most was the ease of natural organisation for common tasks, such as cooking, cleaning, making bread and getting clear water from the lake. Obviously it wasn’t always easy, as we had electricity for only a few hours per day, and because the boat was trapped in ice we had no showers or toilets. For sure, being used to living in different environments helped me, as it created a kind of flexibility which is an absolute necessity in this situation of collective living in a hostile natural environment.

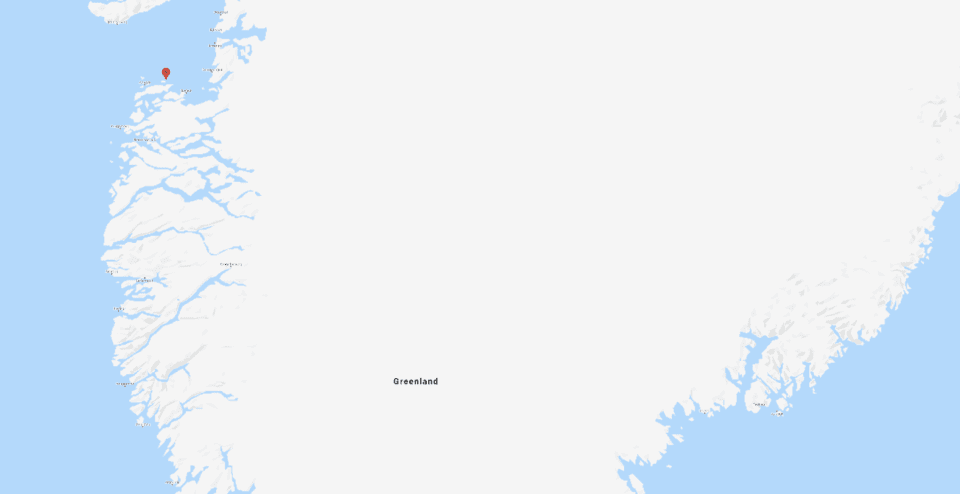

We had a lot of meeting time with the inhabitants of Akunnaaq, which is located 45 minutes away. It was so great to see how people were welcoming and spontaneously invited us to have dinner or tea in their homes. For the work, we were totally free to organise ourselves as we wanted and we made a great team, helping each other every day and creating a real synergy. A few days before our departure, we organised a day to present our works and I was really surprised to see how naturally our installations were complementary and created a coherent body of work.

A: To what extent did the location of the residency inspire or affect your art practice?

SC: I have to say that there is no place I’ve ever seen on Earth as different as Greenland. I felt like I was living on the moon.

The place affected my work in terms of organisation, as everything takes much more time. When you have to get dressed like an astronaut each time you want get out, and it takes ten minutes to undress just to take something you had forgotten inside. Greenland really changes your perception of time, so you always have to be open to the unexpected. Even on board, organisation was the key point. As I needed electricity to work on my pictures, I had to be sure not to miss the electricity period.

I think my approach to harvest my photographic material was close to the concept of “derive” as described by Guy Debord: to wander without a geographic goal, guided by emotions and subjective effects of the places.

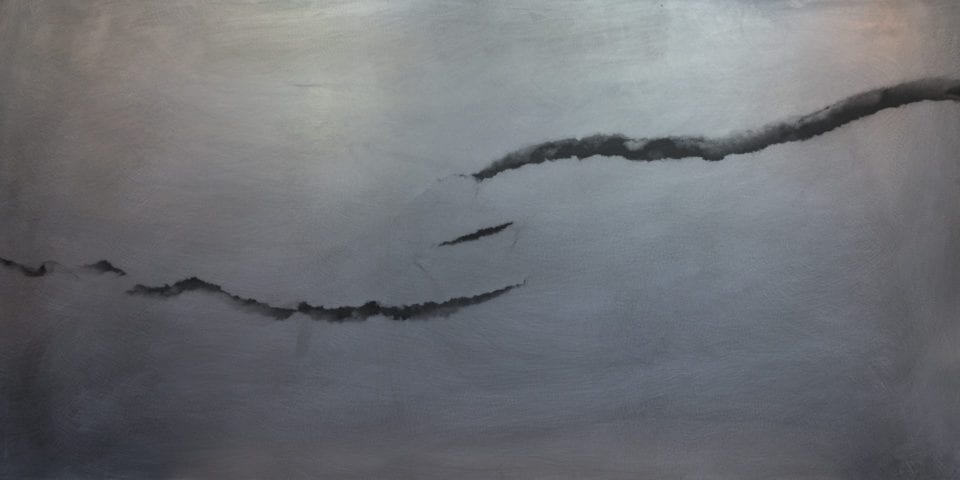

The most important thing was how the land affects my creative habits. To allow for oxidation of steel, my pictures have to be in black and white, then I remove the whites to let the metal appear. I needed highly contrasted pictures. It was easy in Costa Rica, with the jungle, river and beaches, but an obvious thing I hadn’t anticipated was that almost everything is white in Arctic. Thus, the land still reflects all the colours of the sky. On some days everything is orange, on others the land is pink and at the end of the day the landscape and sky turn violet. Colours are truly amazing but for somebody who needs contrast and shape it was a real challenge. Finally, I succeeded to obtain good results by taking backlighted landscaped and closeup textured shots of the ground.

A: Can you expand upon the Akunnaaq series of works and why the use of steel as a material is of importance to you?

SC: I can’t separate Akunnaaq from Paquare, as it’s just the second episode of a more global work and I’m thinking about subtitling them Territory #1 and #2 to enlighten the link. As we’ve discussed, the narrativity of my work is in its auto-destructive property and in the potential interaction that the viewer can have with my works – that’s why steel is so important. If we want to interpret it, we can say that steel represents culture by opposition to nature; it’s our civilisation and our human activities which destroy our environment. But at a practical level, its physical properties are for now the only ones I have found that allow this mirror game between environmental and work destructions.

But for sure Akunnaaq has its own specificity. Especially in the narrative. Usually a debacle happens in this region in the middle of June; this year the debacle happened in April, in the middle of my journey. Thus, when you look at the whole series you can really see the progressive warming and meltdown, especially in the closeup shots. The first ones present fully-packed ice, the second show the cracking ice and it’s pursued gradually until my last shot, a few days before my departure, in which there is no ice anymore.

A: How does working with different materials inform your photographic practice?

SC: It’s the limits of photography, as aesthetic object or vector of meaning, that leads me to work with different materials with the willingness to cause or allow an interaction by opposition to the usual passive reception. I began with steel and wood, but it’s literally limitless. Each material has its own physical properties and it’s always a challenge to find a way to combine it with photography.

I’m in a perpetual learning process. For example, I wanted to realise a series on the ambivalence in urbanisation as a reflection of our own ambivalence. I began to do research on urbanisation, the sustainable cities concept and gentrification. I had the opportunity to spent ten days in New York, and clearly it’s a perfect city to convey our contradictions. I walked across the city to shoot in double exposure, to illustrate contradictions such as freedom and surveillance, luxury and deprivation, and so on. Then back home, I wondered to myself what to do with my pictures to involve the viewer, and how to put them at the core of the work and show our own private ambivalence and incoherence through my work.

The solution was obvious: use mirror as a support. But due to the reflective property it was impossible to use the process that I has used for steel. In fact it’s more my research that informs my photography practice and the use of different materials than the opposite. For sure, sometimes I notice a material with interesting properties and I write it my notebook for a later potential use, but most of the time the concept comes first.

A: Akunnaaq is the name of a village in Greenland, located near the residency location aboard Manguier. Why is Akunnaaq the name of your series?

SC: Your question made me smile because the only thing I dislike in the artist’s practice is to find names for all of my works. A name is very important as a clue or another kind of contact with the viewer. But I don’t know why I can’t think of something relevant. Most of my work’s names are very personal and linked to a feeling or a memory. They’re addressed to someone or just to me. Sometimes it’s a private joke. But I can’t do that for a series, it has to be related to the body of work, thus I go straight to the most simple option. Paquare (sometimes written Pacare) is the name of the river which flows into the Caribbean sea where we had patrolled during my volunteering in Cost Rica, and Akunnaaq was the closest named place during the Artic residency. To be honest, the closest named place was the bay in which the boat was trapped but it’s name is Qammavinnguaq. I guess it’s not the most easy name to remember and spell – for me at least.

A: Has your life and art practice changed since your return to France? In what ways?

SC: Not as much that I would like. It’s terrible to see the ice breaking earlier than predicted and the thermometer over the 0° somedays instead of the usual -10° or -20°. To reduce waste, to consume less or better, we all do this. But it’s not enough. I live in a capitalist system and I contribute to it. My little attention or privation is not enough. You know, there is a huge cathartic part in my work. When I point to our responsibilities and our contradictions, before all of that I talk about my own contradictions and my involvement in a system that I reprove. But a zero-impact life represents a huge sacrifice and without being ready or skilled enough to live in an autarchy, I’m at least thinking about a new project with an almost nil environmental impact. I can’t say more about it now, but maybe I can give you one clue: Henry David Thoreau.

A: What are your current inspirations?

SC: Artistically Gustav Metzger before all, but I’ve found inspiration everywhere. I can’t let my mind be unoccupied and I’m a bit of a bookworm. When I can’t read, I listen audiobooks. Physics, sociology, philosophy, psychology, economy and gender studies…I read anything that can contribute to enlarge my comprehension of the world I live in. But it’s like the Danaïdes barrel: how interesting can it be to make new connections, as it always lead to more and more questions. I guess that creation is a way for me to make things stick together and communicate the mess inside my brain.

A: What other projects and exhibitions do you have coming up in 2020

SC: This year is rich in projects and challenges. I’ve planned to create a new sequel to Paquare and Akunnaaq: it’s called Yaté. This series will be produced in New Caledonia where nickel exploitation has terrible consequences on the environment. I’ve planned to meet local journalists and create filmed interviews with inhabitants who want to talk about their relationship to their territory to bring a new dimension to my work, by proposing documentation to the viewer as a complement to my plastic works. There is a lot of pressure on this project because it’s directly linked to my academic research. It will be presented for my MFA and will condition my potential admission to a PhD.

During the Manguier residency I had the chance to live with Heliabel Bomstein, a writer and Arthur Lecercle, a musician and composer in which they worked together to compose an album on board called Songlines. During the residency exhibition we proposed a listening of their album with a projection of my pictures and it worked very well. So we’ve decided to compete for the Swiss Life 4 Hands Prize which allows a grant for a collaboration between musicians and photographers.

I also have a project with the WWF. They contacted me last June to create a work using recycled plastic but the deadline was too close for me. Plastic is not a material I use but I’ll have a year to work on this and it will be really interesting for me. Removing plastic from rivers and oceans and finding a sustainable way to reshape it, and then work with pictures. That’s exciting.

I’ll also have to find a new gallery and an agent to represent me because my previous one in Marseille has unfortunately closed its doors. It’s not the most fun part of an art practice but it represents a lot of time to search for exhibitions.

On the exhibition side I’ll have some personal work shown at the Ozart gallery in Toulouse and also in the Domaine de Combilaty, an amazing renovated castle in Brouilly. We’ll also have a collective exhibition of Artists in the Arctic in St Grégoire, 25 January-21 February, thanks to the artist Bénédicte Klène, and a book publication presenting the works created during the 2019 edition of Artists in the Arctic.

There’s another exhibition project in the contemporary art museum of a European Capital, but as nothing is confirmed yet, I prefer keep it a secret…readers can keep informed by checking my website or following me on Facebook or Instagram. And for sure, I’m always open to new exhibitions and opportunities.

www.sc-camors.com

www.instagram.com/theascch

www.facebook.com/ascch.music

Lead image: The Spider in my Mind.

The work of Salomé-Charlotte Camors appears in the Artists’ Directory in Issue 87 of Aesthetica. Click here to visit our online shop.