“How can you care about the image of a landscape, when you show by your deeds that you don’t care for the landscape itself?” Theses are the words of British artist, designer and 19th century poet William Morris, known for his intricate and adorned patterns. His designs, often based on poppy wreaths, twisting vines or flowering strawberries, represented an enduring interest in the environment. The artist was an activist of his time who “abhorred the cheap and cheerful products of manufacturing, the terrible working and living conditions of the poor.” In opposition to the Industrial Revolution, he preferred individual craftsmanship and sustainable production, even using natural dyes in his own work. From 21 October – 18 February 2024, William Morris Gallery, London, presents Radical Landscapes, an exhibition that explores the natural world as a space of inspiration, social connection and cultural protest. Organised in collaboration with Tate Liverpool, it displays work spanning two centuries and features more than 60 pieces by artists including Claude Cahun, Derek Jarman, Jeremy Deller, JMW Turner and Veronica Ryan.

The first part of the exhibition reflects on 18th and 19th century perspectives, looking at historical paintings and prints by JMW Turner and John Ruskin. It presents the work of artists who played a significant role in Morris’ own life – those who also saw green spaces as places of timeless leisure, bucolic life and rural identity. Viewers then move into the second section that explores acts of trespass and belonging, thinking about the ways in which communal rights to land have been encroached upon by enclosure, privatisation and commodification of green spaces. This process is the subject of Hurvin Anderson’s paintings and Turner Prize winner Veronica Ryan’s sculptures, pieces that reflect on journeys of movement and migration whilst critically examining imperialist expansion.

The exhibition then moves to the overlap between art and activism. This is approached by Keith Robert Foster, a photographer who documented the historic M11 link road protests. In 1994, a road was proposed to link central London and the docklands with East Anglia. In preparation for construction, the Minister for Transport announced that there would be 263 properties scheduled for demolition, displacing 550 people. As a result, protestors occupied a terrace of 35 houses in Claremont Road in Leytonstone, east London, for eight months. The street was completely occupied by protestors, except for one original resident who had not taken up the Department for Transport’s offer to move, 92-year-old Dolly Watson, who was born in number 32 and had lived there nearly all her life. The protestors subsequently named a watchtower, built from scaffold poles, after her. This can be seen in a sepia yellow photograph. In addition to warning signs, banners cover the tower’s scaffolding, bearing phrases such as “Stop the Roads, Not the Protest.” Elsewhere, Foster captures graffiti sprayed onto a gutted-out house. Painted green trees and upside down figures pop with colour in an image that makes a powerful stand against forced rehousing.

In the third section are Chris Kilip’s documentary photographs. The gallery highlights the artist’s project in Lynemouth – where he photographed “sea-coalers,” a term used to refer to people who harvested coal washed up on beaches from local mines. For a year, the artist lived in a caravan on the sea coal camp, documenting the lives of those around him. These images document the harsh Northumbrian seaside. In one image, a young girl wrestles with a hula hoop. In the background lies a large lump of sea coal, a burnt out fire and the metal bones of a bedstead. The picture captures the real life experience of living in a mining community – right down to the children who had to entertain themselves when there was nothing else.

The exhibition is organised in collaboration with local artists, campaigners, foodbanks and allotments. A public programme also runs alongside and expands beyond the Gallery’s walls into the wetlands, forests and green spaces of Waltham Forest. It invites participants to reassess their relationship with local landscapes, inviting them to respond to the climate crisis. In so doing, Radical Landscapes advocates the very action William Morris demanded. It pays attention to undocumented communities and subcultures, reflecting on issues of freedom and migration. It recognises that environmental degradation does not affect us all equally. Instead, it is those who are vulnerable, those who already live in poorly built homes or who suffer from social deprivation, that will feel the climate emergency more immediately. This is a show that realises that – asking us to look to our environment and peers with awareness and empathy.

Radical Landscapes | 21 October – 18 February 2024

Words: Chloe Elliott

Image Credits:

1. Chris Killip, Helen and her Hula-hoop, Seacoal Camp, Lynemouth, Northumberland, 1984 © Chris Killip Photography Trust/Magnum Photos, courtesy Martin Parr Foundation.

2. The eviction of ‘The Chase’ camp at Newbury, 1996 © Andrew Testa.

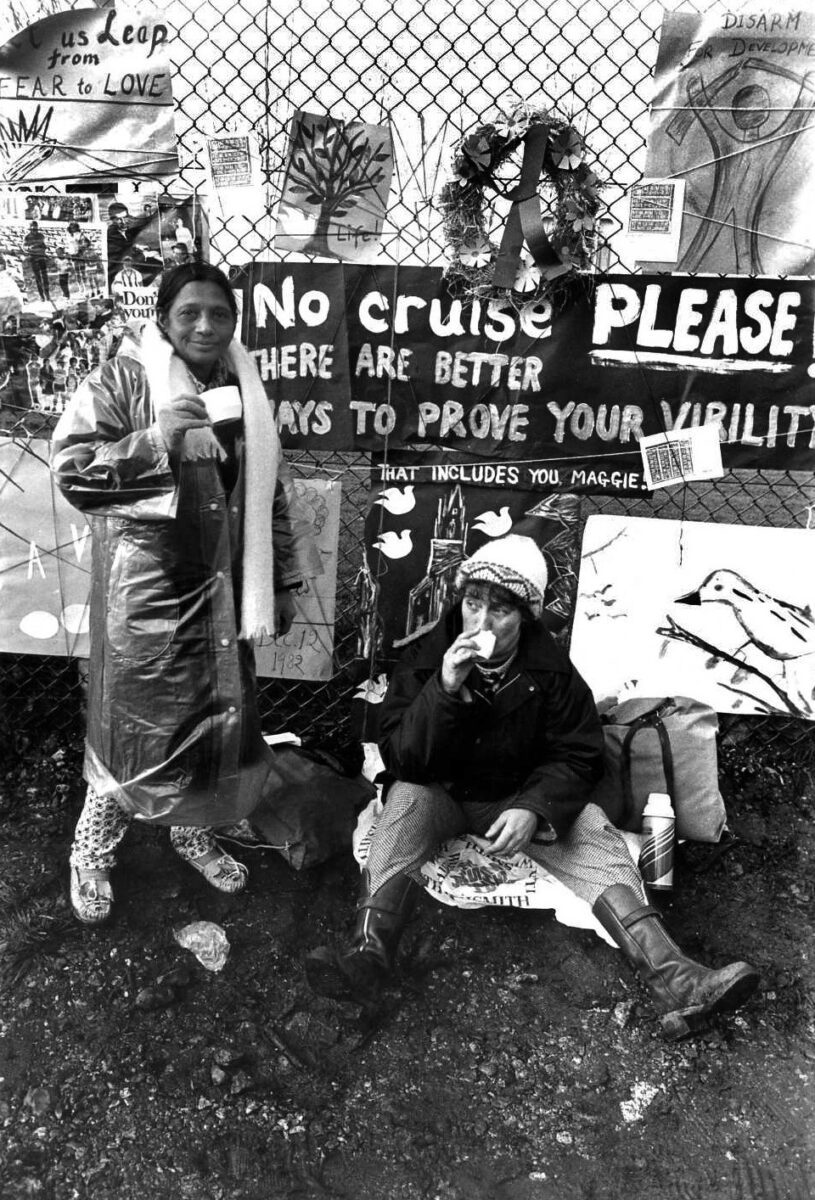

3. Greenham Common ‘Embrace the Base’ Protest, 12 December 1982, Jenny Matthews © Jenny Matthews, Format Photographers at Bishopgate Institute.