Isaac Julien’s Lessons of the Hour is a poetic meditation on the life and times of Frederick Douglass (1818–1895), a visionary African American writer, abolitionist and a freed slave, who was also the most photographed man of the 19th century. Victoria Miro presents an extended reality (XR) exhibition of the photographic works, available exclusively online on Vortic Collect.

A: Douglass was the most photographed man of the 19th century. For him, photography was a way of achieving autonomy over the way African Americans were depicted. Technology, he believed, could influence human relationships. How do your works tap into the ethics of representation, translating Douglass’ vision through contemporary media?

IJ: This theme permeates a lot of my work, which takes a critical but – as with Douglass – a compassionately open view on “fixed” categorisations around history and aesthetics. Douglass’ writings on photography and its liberating role were not completely neutral. Photography was able to create subjectivity through its indexical codes. That is the reason why I focused on these technologies of representation. Traditionally, history tends to relate to the genre of documentary, which has a whole set of visual and discursive parameters. My work has tried to develop a more open, and perhaps more critical, stance.

My work often establishes a poetic view on historical figures and their stories, dealing with representation through the combination of many elements: factual history, aesthetic expression, subjective narratives, political background etc. In Frederic Douglass’ case, the issue was problematised by himself: in his own image as the most photographed person in the US of the 19th century, and also in his theoretical reflections. After all, it was an iPhone which created the world’s response to the sad spectacle of black murder. I think Douglass would have a few words to say about that!

A: You have produced a roster of “characters” – including Douglass and many individuals connected to him. To what extent are you questioning the idea of truth and perspective?

IJ: This goes back to my criticism of the way we look at history. In cinematic terms, common sense has established the idea that all films belong to a specific genre – that films about otherness and politics should take a realist-documentary form. I have been challenging this notion for over four decades. The realist-documentary form is a canon which omits the question of “desire in images.” I make a point of conceptualising the inappropriate – embedding desires and emotional relationships into the work. When I create a piece inspired by historical characters, I question the preordained notions of truth and perspective, interweaving the subjective, political, emotional and cultural realms in mutual connection. In a way, the most truthful representation is, I think, a combination of all of those factors, and not an attempt at some utopic idea of objectivity.

A: In what settings do the characters exist? How have the locations been chosen?

IJ: The characters exist in history, and therefore in the historical places that were meaningful to them, but they also exist in their own inner lives. My work tries to poetically navigate both spheres, so locations usually alternate between actual places which played a role in those people’s lives, like Douglass’s time in Edinburgh or Lina Bo Bardi’s Salvador, and places which are symbolic to reflect on thoughts and ideas from those characters: and therefore you will also see Douglass at the Royal Academy and hear Lina Bo Bardi’s words in an ice cave in Iceland.

A: In the midst of global protests connected to Black Lives Matter, how do your works reference the “zeitgeist” of Douglass’ era and critically compare it to today?

IJ: The world we see today, with Trump, Brexit and so many forms of racial essentialism and terror, is a world which Douglass would be disappointed and even surprised with, more than a century after his deaths. I didn’t wake up yesterday to Black Lives Matter but it took a camera image of George Floyd’s murder for the white world to wake up! Since then, I have been snowed-under with interview requests like this and requests to show my work, which is a great thing but it is also disheartening to see how current and pertinent Douglass’ message still is. So, in a way, I don’t even need to force references or comparisons. I did make an experimental activist video work in 1983 called “Who killed Colin Roach?” Need I say more? But back to the theme of comparisons, Douglass’ words are already strong enough, so I only included some more subtle correlations with present days: for example, as I mentioned, around the end of the film you see 4th of July fireworks over Baltimore, in reverse, alongside drone footage from the Baltimore Police Department, tracking the movements of people during the 2015 uprising after Freddie Gray was killed. One needs no enforcement of correlations since, especially for a younger generation, it is clear that we are at the most critical point of this learning curve towards some racial justice which was Douglass’ very life mission!

A: What does your work tell audiences about the formation of systemic racism and the lessons that still need to be learnt today?

IJ: That lessons are never over! For example, recently a work that I made as a student at St. Martin’s School of Art in 1984 called Territories (an experimental film about policing at the Nottingham Gate Carnival and sounds systems and dub) was acquired by a German museum. This is a moment of broad reckoning.

A: How does the Extended Reality bring these images to life? What do they add to the works, both formally and conceptually?

IJ: My use of multiple screens – creating an immersive experience – proposes a multi-faceted experience of time as a means for re-inventing our relationship with the duration of audio-visual languages. Of course, subjectively speaking, there is a fragmentary dimension to any moving image experience, which could be compared to AR or CX. But what my multi-screen works do is materialise this process, widening the possibilities of interpreting and reflecting upon narratives, particularly non-linear narratives.

As we become more and more used to the saturation of media and visual stimulation, we have all become distracted spectators; so, to redirect our attention and sensibilities, you could say that my artworks combine the multiple audio-visual inputs with a meditative pace. So I think there is a form of re-education of our senses, even though this is not my main goal as an artist.

Interview with Aesthetica’s Assistant Editor, Kate Simpson

Isaac Julien: Photographic works from Lessons of the Hour – Frederick Douglass is at Victoria Miro online, and on the Vortic Collect app, until 29 August. To view, click here.

Credits:

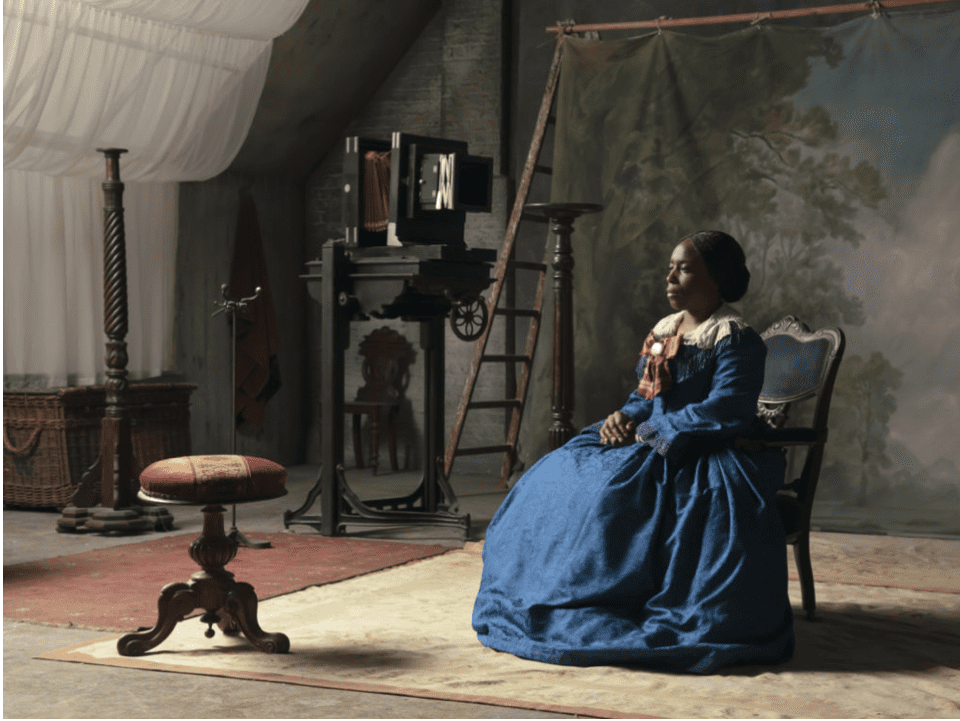

1. J.P. Ball Studio, 1867 Douglass (Lessons of the Hour), 2019 Framed photograph on gloss inkjet paper mounted on aluminium 57 x 76 cm 22 1/2 x 29 7/8 in Edition of 6 plus 1 artist’s proof © Isaac Julien Courtesy the artist, Victoria Miro and Metro Pictures.

2. Isaac Julien, North Star (Lessons of the Hour), 2019. Framed photograph on gloss inkjet paper mounted on aluminium 160 x 213.3 cm 63 x 84 in Edition of 4 plus 2 artist’s proofs.Courtesy the artist, Victoria Miro and Metro Pictures.

3. Isaac Julien, Lessons of the Hour (Lessons of the Hour), 2019. Framed photograph on matt archival paper mounted on aluminium 160 x 213.3 cm 63 x 84 in Edition of 6 plus 1 artist’s proof.Courtesy the artist, Victoria Miro and Metro Pictures.

4. Isaac Julien, The Lady of the Lake (Lessons of the Hour), 2019. Framed photograph on gloss inkjet paper mounted on aluminium 160 x 213.3 cm 63 x 84 in Edition of 6 plus 1 artist’s proof. Courtesy the artist, Victoria Miro and Metro Pictures.

5. J.P. Ball Studio, 1867 (Lessons of the Hour), 2019 Framed photograph on gloss inkjet paper mounted on aluminium 103.9 x 138.5 cm 40 7/8 x 54 1/2 in Edition of 6 plus 1 artist’s proof © Isaac Julien. Courtesy the artist, Victoria Miro and Metro Pictures. Courtesy the artist, Victoria Miro and Metro Pictures.